When I began planning my own trip to Japan, much of my research happened on TikTok. The app’s endless scroll of short clips, from hidden ramen spots in Kyoto to serene onsens tucked in the mountains, felt authentic and spontaneous. Yet, as I saved video after video, I found myself wondering: Am I seeing an authentic version of this destination, or just one that fits within the social media aesthetic?

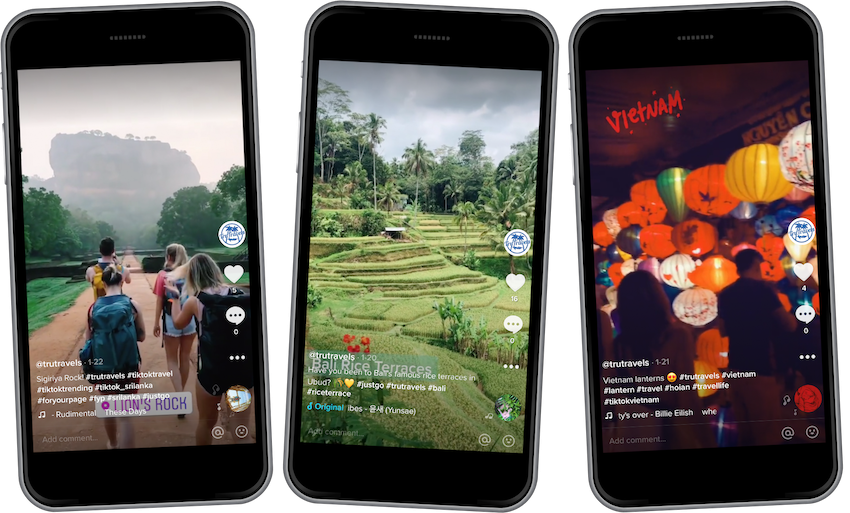

In the last decade, social media has profoundly altered the ways people imagine, plan, and experience travel. Platforms like Instagram once reigned supreme, inspiring millions with filtered images of iconic destinations. However, TikTok has become a significant cultural force in recent years, changing not only what people want to see but also how they travel. TikTok enables viewers to consume travel material in a fast-paced, highly visual manner that seems genuine and intimate thanks to its algorithm-driven short-form films. Consequently, once overlooked or unknown locations are brought into the public eye, and “must-see” viral locations draw larger crowds of tourists.

TikTok represents a major shift in how travel decisions are influenced, moving beyond the limits of traditional tourism marketing. In particular, TikTok’s peer-to-peer storytelling encourages authenticity, which changes travel preferences and broadens the scope of travel beyond conventional locations. But there are also disadvantages associated with this change, such as excessive tourism and superficial engagement with the location. By transforming regular users into travel marketers, TikTok has drastically altered the way people travel around the world. At the same time, it has increased overtourism at popular destinations and opened up new avenues for peer-driven, authentic discovery of lesser-known locations.

Tik Tok is criticised for encouraging and producing overtourism in the travel industry. Easy-to-consume content is rewarded by the platform’s algorithm, and this frequently translates into short videos of eye-catching places. Destinations receive enormous waves of attention as a result of these videos’ rapid virality. However, this virality frequently reduces travel to a list of “must-see” sights, depriving places of their cultural character and turning them into backgrounds for popular dances or sounds. This can be seen in Elliott (2024)’s research that the platform’s enormous influence is demonstrated by the fact that over 70% of TikTok’s European audience believes they are likely to plan a vacation based on suggestions they have seen on the app.

Tik Tok promoting excessive tourism can be easily seen in Kyoto, Japan. Kyoto’s popularity can be seen in the 47% increase in tourists and with the hashtag #kyoto, which has more than two million posts alone (Naoko Tochibayashi & Ota, 2025). This hashtag and Tik Tok portray the city as a recurring visual template rather than a living place: tourists wearing kimonos floating through Gion, cherry blossoms captured in romantic clips, and streets that are described as the “authentic” Kyoto. According to Burtis and Wise (2025), this attention economy results in what the locals refer to as “tourist pollution”, not just the evident issues of overcrowded streets, loud traffic, and overloaded public transportation, but also a more profound depletion of daily life. Residents lose their daily routines when entire neighbourhoods are frequently set up for tourists and their cameras, activities like grocery shopping, school runs, and even the calm of an evening are transformed into theatrical backdrops. This demonstrates how TikTok transforms an urban environment into a performance venue where algorithmically driven exposure demands take priority over the requirements of the local people. Here, the platform’s design incentives are important since TikTok encourages creators to stage situations that are aesthetic rather than convey cultural significance by prioritising visually appealing, easily digestible components over context.

The location flattens as a result of this. Beautiful and stripped of historical and cultural complexity, cultural practices and material objects, like the kimono, become symbols for digital consumption and aesthetics rather than important traditions. This goes against popular notions of authenticity in travel, as tourists are now urged to “tick off” spectacles optimised to become viral instead of seeking deeper cultural interaction. Japan has implemented dual pricing for locals and tourists at popular locations, restricted access to places like Mount Fuji and more, prohibited photography in private regions like Gion, developed systems to monitor and visualise traffic, and promoted lesser-known spots in order to disperse visitors in an effort to combat overtourism in Kyoto and other destinations (Naoko Tochibayashi & Ota, 2025). Therefore, the example of Kyoto raises the question, should platforms be held accountable for distributing cultural spaces as commodities, or should tourists themselves bear the ethical burden of resisting checklist-style travel? When viewed in this light, Kyoto is not only a case of overcrowding but also a demonstration of how algorithmic engagement transforms cultural life, posing pressing issues regarding how societies might recover their right to regular routines from the conventions of digital display. In contrast to conventional marketing, TikTok’s impact is quick and widespread, fostering a sense of cultural urgency to visit particular locations “before the trend dies.”

However, some contend that TikTok does not mark a significant shift in the way that travel is promoted. Rather, it expands on established destination marketing strategies that were influenced by airlines, travel agents, and earlier social media platforms such as Instagram. Travellers were inspired by glossy magazine photos, commercial ads, and later influencers’ Instagram feeds long before TikTok. From this perspective, TikTok is merely a new distribution method for the same advertising theory.

As an example, look at Paris. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, and Montmartre have been staples of travel promotions. The same clichés that have previously been captured in postcards, movies, and Instagram feeds, the croissants in corner cafés, sunset at Trocadéro, are frequently repeated in TikTok videos with hashtags of Paris. Comparably, Bali’s beaches, rice terraces, and yoga retreats were extensively promoted even before TikTok, with travel companies and packaged holidays shaping the island’s reputation worldwide. TikTok makes these websites more accessible to younger audiences, but it doesn’t radically alter the locations that are most popular in the world.

According to Jani et al. (2024), social media has always served as “free advertising,” with regular tourists creating material that promotes tourism destinations. Therefore, TikTok is innovative in scale but not in its form; its algorithm and structure amplify rather than modify preexisting patterns (Jani et al., 2024). Travel agencies and airlines are also fast to adjust, hiring influencers to create content that is suitable for TikTok. For instance, Tourism Australia’s Come and Say G’day campaign combined corporate branding with the light-hearted tone of TikTok with TikTok-specific content that featured animated characters interacting with iconic Australian landscapes and people (Tourism Australia, 2025).

The tourist business has long benefited from mediated visual culture, whether it was through Instagram influencers in the 2010s, Lonely Planet guidebooks in the 1980s, or glossy airline brochures in the 1960s. Simply put, TikTok is the most recent development in this long-running cycle of destination marketing.

Although critics point to TikTok for encouraging overtourism, the app also reinterprets travel in ways that go beyond conventional advertising. TikTok thrives on short-form, user-generated material that emphasises authenticity, as opposed to slick brochures or professionally produced commercials. Due to the platform’s design, which encourages creativity, relatability, and storytelling, regular travellers may share their experiences in ways that appeal to a wide range of viewers. This dynamic is significant since it democratises travel storytelling, shifting influence away from corporations or government tourism boards and into the hands of individuals.

Peer-to-peer storytelling is a key component of this reinterpretation. Users view other travellers’ honest descriptions of places rather than being directed there by well-produced ads. For instance, a TikTok video of a remote hike in Tasmania can include unsteady camera work, muddy shoes, and worn-out commentary, yet this “realness” frequently appeals more than a marketed picture of the same place. As viewers see that they are interacting with real recommendations rather than staged marketing, researchers like Marwick (2013) contend that such “micro-celebrity” tactics foster trust between content creators and audiences. Younger generations of visitors who are wary of traditional advertising find this sense of authenticity especially appealing.

Additionally, TikTok has made it easier to rediscover places that have been forgotten. The For You Page algorithm frequently presents content from smaller producers in surprising global locations, bringing attention to areas that have not been included in popular vacation advertisements or more viral videos. Tik Toks showing Albania’s coastline, for instance, went viral in 2023, turning the nation from a niche tourism destination into a popular summer vacation site for European tourists. Similar to this, creators have made little towns like Chefchaouen in Morocco and Hallstatt in Austria famous on TikTok for their unique beauty long before they became the focus of major tourism campaigns. In this sense, TikTok is not only reiterating established tourist routes but also transforming them by highlighting locations that were previously unimaginable in the global travel landscape.

The format of TikTok content itself also contributes to this reframing. Short videos encourage creators to highlight not only iconic landmarks but also small, everyday moments such as a café tucked in a side street, navigating public transport, or local street vendors. By focusing on culture and living experience rather than merely “Instagrammable” scenery, these micro-narratives offer an in-depth overview of a location. Unlike social media sites like Instagram, where aesthetic perfection frequently rules, TikTok’s editing features and sound trends encourage humour, openness, and even vulnerability. This change expands the idea of what is “travel-worthy” and promotes a more nuanced interaction with travel locations.

The way that TikTok encourages collaborative travel planning is another significant effect. Viewers do more than just consume videos, they also leave comments, pose queries, and even add personal anecdotes to videos. For example, Tik Tok creator @Keagies posted a video of his 4th day in Japan and what he did that day, many users commented on that video asking questions about money, public transport and more (Tik Tok, 2025). @Keagies responded to comments, answering their questions based on his advice and travel experiences (Tik Tok, 2025). This interactive feature implies that TikTok operates simultaneously as inspiration, knowledge, and discourse, giving travellers a more comprehensive approach to planning for travel.

Another example of TikTok’s role in collaboration and the exploration of previously overlooked places can be seen in my own life. I am currently planning a trip to Japan, and my initial decision to travel there was heavily influenced by the aesthetic TikTok videos I encountered, which sparked my interest in the country as a destination. TikTok has also shaped my itinerary. For instance, I had planned to visit Nara Park in Osaka, famous for its free-roaming deer. However, after seeing multiple Tik Tok’s depicting the deer aggressively pursuing tourists for food and the park being overcrowded, I reconsidered. One video in particular offered the alternative of Itsukushima Island, which has deer as well, but in a more serene, uncrowded setting with breathtaking views. Similar to the previous example of @Keagie’s videos, TikTok has given me useful travel advice and options, which ultimately made things simpler for me to plan a more pleasant trip. This demonstrates how TikTok not only inspires travel but also refines and redirects it in practical, personal ways.

TikTok has grown to be a significant player in the travel sector, changing the way people discover, enjoy, and advertise destinations. Its impact complements, rather than entirely replaces, conventional tourism marketing strategies, even as it brings in new kinds of peer-to-peer storytelling that emphasise authenticity and accessibility. In this way, TikTok simultaneously advances and somewhat disrupts current methods for travel promotion. In the end, the “TikTok effect” changes how people think about travel in general and where to go, moving away from polished, brand-led ideals and towards community-driven experiences. The current difficulty is striking a balance between the pressing need for sustainable and responsible tourism and TikTok’s ability to revolutionise travel. TikTok will continue to be a useful tool and a complicated force in the world of travel as governments, tourism boards, and tourists adjust.