With 360,000 followers watching, lifestyle influencer Marlena Velez transformed a $500 theft into a meticulously curated haul video, presenting the stolen goods as a must-have that her audiences must “run, not walk” to get. This extreme example highlights the performative and continuous consumption inherent in influencer culture. Every scroll on social media exposes users to the latest “it” products, life-changing home gadgets, and aesthetic seasonal hauls—much like a modern version of TV shopping channels, which creates a constant stream of temptation and normalises the accumulation of excessive material possessions. Overconsumption is best defined as the unsustainable, rapid consumption of resources, such as cheap and poorly crafted online products. This is problematic, as supply chains often struggle to keep up with demand, intensifying ethical issues such as the exploitation of workers and child labour, in addition to the depletion of natural resources.

Nevertheless, consumption continues to rise, especially online, largely driven by influencers. More accessible and friendly than traditional celebrities, social media influencers are the new trendsetters in society (Dinh & Lee, 2024). These are personas that often create online content showcasing a particular lifestyle or promoting specific products (Dinh & Lee, 2024). As a result, Influencer content, from lifestyle posts to haul videos, normalises overconsumption by framing often unnecessary and excessive purchasing habits as aspirational, socially valuable, and essential to personal experiences.

Influencer-driven aesthetics and lifestyles as a catalyst for overconsumption

Influencers on social media normalise consumption-driven identities through aesthetics and lifestyles, thus subtly and overtly shaping spending norms. On social media, influencers promote and endorse a plethora of aesthetics, including clean girl, VSCO, Y2K, kidcore, dark academia, and many more. The proliferation of these online aesthetics promotes overconsumption, as these highly curated looks are rarely achieved naturally. Users tend to tailor themselves to the aesthetic they deem desirable through material purchases to ‘look the part’. Take the clean girl aesthetic as an example – although it aims to represent minimalism and natural beauty, the extensive catalogue of products required to achieve the look is ironic, as it fuels another consumption trend. For instance, one must buy a $40 Dior lip oil, a $20 Rare Beauty blush, a $70 Stanley Cup, and a 10-step skincare routine, a common trope in the aesthetic.

This echoes earlier trends, such as the VSCO girl, which promotes a youthful and carefree image, while requiring items like the Hydro Flask, Mario Badescu mist, Birkenstocks, and more.

What makes these aesthetics heavily problematic is that they do not simply encourage the purchase of any lip oil or water bottle; they prescribe specific, often very pricey brands. Individuals may be compelled to make an unnecessary purchase to replace products they already own, simply for the sake of the brand name associated with the aesthetic. Moreover, the overconsumption intensifies once an influencer signals that a trend is out, prompting followers to abandon previous products and jump on another aesthetic bandwagon. For example, Kayla Trivieri, a self-proclaimed mob wife, stated in a TikTok, “Clean girl is out, mobwife era is in, okay?” The mobwife aesthetic being coined is opposite to the clean girl, featuring “red lips, animal prints, and flashy jewellery.”

While individuals ultimately retain discretion over their choices, remarks from influencers may render embracing an outdated and overdone aesthetic shameful or undesirable. As a result, influencers cultivate a materialistic cycle, where unnecessary consumption spikes with each emerging trend, only to repeat when something new takes its place.

A study conducted by Dinh & Lee (2024) found that constant exposure to influencers transforms ordinary consumption into conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption is defined as the investment of time and money in unnecessary and ineffective products to elevate one’s self-image (Dinh & Lee, 2024). While users may have previously made purchasing decisions based on practicality and necessity, the persistent awareness of the influencer lifestyle, defined by high fashion and extravagance, leads to an upward social comparison (Dinh & Lee, 2024). Comparing oneself to these curated lifestyles creates a sense of deprivation and a fear of missing out (FOMO), which may reinforce the drive to acquire a product that signals high status. FOMO may threaten self-esteem, compelling followers to enhance their self-image by adopting similar purchasing behaviours as their idolised influencer. The greater the fear and perceived inferiority of one’s lifestyle, the more likely individuals are to engage in conspicuous consumption—purchases motivated by status display rather than functional needs.

Take blind box toy influencers, for example. They frequently showcase their hard-to-obtain figures, emphasising their rarity through their dialogues in unboxing or collection videos. For instance, Pop Mart’s Labubu has emerged as a highly sought-after bag charm, often spotted on royals, celebrities, and influencers alike (Zhang, 2025). Through influencers’ constant display of these toys, they are transformed into a symbol signifying affluence, spending ability, and financial status. This symbolic association drives consumption, encouraging followers to emulate such unnecessary purchases as a form of social signalling and to demonstrate belonging in an influencer-driven culture.

Certain products gain increased desirability when endorsed by a prominent influencer. For example, Lisa, a member of the Korean girl group BLACKPINK, has become a well-known collector and enthusiast of Pop Mart’s character, Labubu (Wu, 2024). As a result, adopting a similar consumption pattern (buying the same product) serves to convey that an individual possesses similar tastes and a personality to the public persona they want to emulate. Overconsumption, driven by the desire to curate an influencer-inspired identity, evolves into normalised conspicuous consumption, where excessive purchases become a routine method of replicating aspirational lifestyles. Ultimately, Influencers’ aesthetics and lifestyles normalise identities driven by consumption, establishing their immense power to shape purchasing behaviours. This relationship sets the stage for examining how overconsumption itself has become a form of entertaining content.

Overconsumption as marketable and effective content

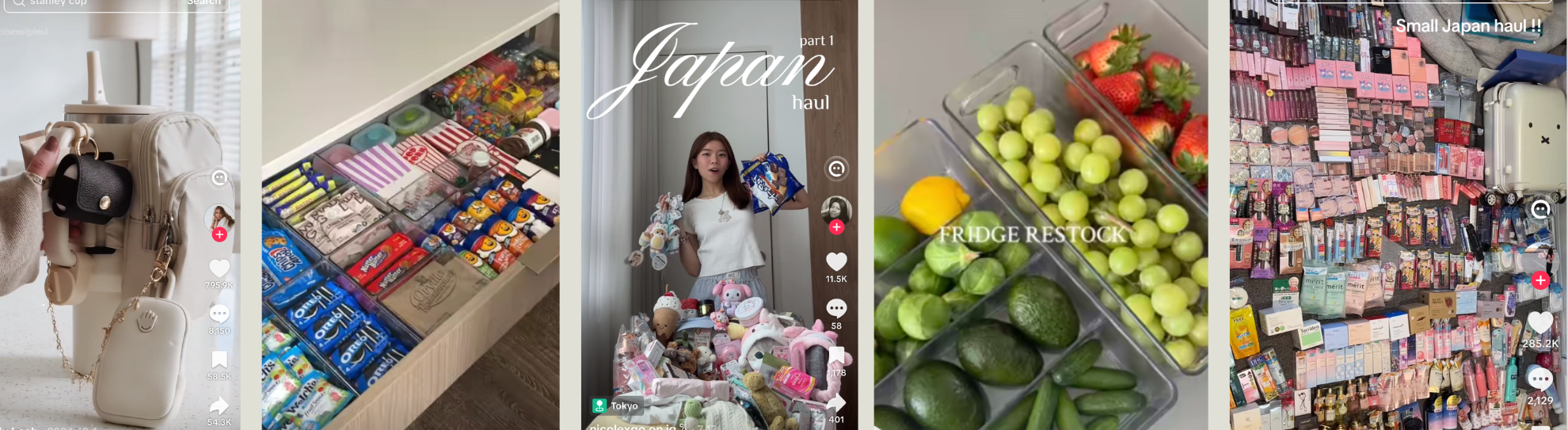

The prevalence of materialistic content in the digital space reframes the once-frowned-upon overconsumption into marketable online entertainment. In recent years, particularly on TikTok, social media has been inundated with content revolving around unnecessary consumption. One trend guilty of this is the restock content, which consists of “visually, aesthetically and auditorily pleasing” short videos that showcase the replenishment of supplies and items (Riboni & Ringrow, 2025, p. 2). Rochelle Stewart of @operation_niki is a prominent creator in this space, featuring exaggerated and often absurd gadgets in her restock videos, including a snack compartment for a Stanley Cup and a penguin-shaped fridge air freshener. At the same time, Catherine Benson of @_catben_ content revolves around transferring items from one perfectly functional container into a newly purchased “more aesthetic” plastic container. For other creators, content follows a repetitive cycle: purchasing, restocking, and then decluttering to make room for yet another major purchase.

Furthermore, this pattern of consumption for the sake of content extends beyond the cleaning influencers to other internet communities. @Coolwithashe on TikTok has gained notoriety among K-pop fans for purchasing an excessive amount of K-pop merchandise, including from groups she does not support or is unfamiliar with (as evident in her frequent mispronunciation of album and member names). These examples illustrate that overconsumption is not only a product of social media but has become increasingly central to content creation. From the earlier article, one creator even admitted that they are unlikely to own so many items if it were not for producing content. In this way, consumption has become a new and prominent form of entertainment online, particularly as platforms enable monetisation for this content genre through affiliate links and brand partnerships. The entertainment value overshadows the wasteful nature and adverse environmental impacts of overconsumption, transforming it from problematic behaviour into profitable and engaging content. For restock videos, the “curated authenticity and apparent relatability” – achieved through techniques such as calculated POV-style camera angles – fosters intimacy and prompts habitual consumption, masking the excessive and wasteful nature of the content (Riboni & Ringrow, 2025, p. 1). Ultimately, both viewers and the creators themselves become desensitised to exaggerated spending behaviours, framing excess as a prerequisite: whether it is an endless supply of acrylic organisers to become a serious restock influencer or a room full of albums to be a certified K-pop fan.

An influencer can even resort to desperate measures to feed into the content creation cycle that revolves around consumption. Marlena Velez, a lifestyle TikToker with 360,000 followers, was arrested for shoplifting $500 worth of home goods from Target, which she later showcased in a haul video on the platform. She documented the entire process, from preparing for the trip to selecting and placing items in her cart. Such instances demonstrate that, more than ever, content creation heavily relies on continuous purchasing, and creators may be compelled to cross legal or ethical boundaries to maintain attention and engagement. This reinforces that a cycle of consumption is an integral content strategy and a requirement within influencer culture.

What we are observing in the influencer landscape also closely reflects research. Social media has a significant influence on consumption, with many purchases driven by the intention to post online (Shah et al., 2023). One study found that over the past 12 months, approximately 84% of its respondents engaged in social media-centric consumption (SMCC) at least once, whilst 70% did so more than twice (Shah et al., 2023). Those who engage in SMCC also tend to exhibit attention-seeking tendencies, with social media responses and interactions influencing their satisfaction and perception of their consumption experiences (Shah et al., 2023). These findings reflect how unnecessary consumption has become a performative aspect of the digital age. Social media reinforces the notion that excessive spending is not only acceptable but also desirable, as platforms grant it visibility and engagement. As a result, the digital space rewards overconsumption by granting it a platform, transforming it into engaging content that enables and indirectly encourages problematic spending behaviour.

Haul Culture’s role in the rise of event-based consumerism

Internet haul culture has converted shopping into a must for personal milestones and events, further fueling patterns of overconsumption. Hauls are a genre of social media content that originated on YouTube, where influencers reveal their purchases to their followers. It garners attention as it caters to followers’ desires to experience the products vicariously before purchasing as a form of instant gratification. However, constant exposure to haul contents becomes problematic, considering the influence of social media on purchasing decisions. In a study examining the influence of social media on pre-purchase decisions, 92.5% of participants actively used social media as a source of information to aid their purchasing decisions (Macías Urrego et al., 2024). They utilise user-generated content about products, which often leads to impulse purchases (Macías Urrego et al., 2024). In this context, hauls extend beyond a simple and engaging showcase of purchased products; they also serve as advertisements, as material consumption is increasingly influenced by what is displayed on social media.

The issue is further exacerbated by the overwhelming number of hauls saturating the online space, from back-to-school to Christmas, birthdays, travel hauls, and more. Hauls are deeply embedded in internet culture, evident in how creators such as YouTuber JuicyStar07 continue to participate in back-to-school hauls even after completing her studies. The popularity of haul culture, supported by influencer content and algorithms, keeps consumption at the forefront of consumers’ feeds and minds. The constant visibility of hauls for most conceivable occasions reinforces the idea that most life events must be accompanied by material purchases – the back-to-school experience is incomplete without a stationery haul featuring the cutest pens and pastel highlighters. In essence, haul culture normalises the idea that consumption is inevitable with each new life event, making audiences more susceptible to excessive and impulsive buying.

Furthermore, the internet haul culture in travel contexts reshapes how individuals perceive and experience travel. On TikTok, there has been a notable rise in country-specific hauls, with popular examples being Japan and Korea hauls, featuring a suitcase worth of products, all carefully laid out. Some videos adopt a humorous tone with trends such as “Did I take advantage of the yen, or did the yen take advantage of me?”

In these hauls, similarities in the products featured can be identified, for instance, skincare in Korea or character merchandise from Japan, implicitly implying that certain purchases are a “must” or essential when visiting a particular country. The proliferation of travel hauls frames shopping (often excessive) as an expected and normalised component of the travel experience. This fuels habitual consumption, wherein individuals are compelled to buy products they already own simply because they are in a different location where certain items are presented as desirable or significant.

The pattern of spending associated with experiences is also reflected in tourist expenditure data. For example, a medium-haul tourist in Taiwan exhibits lower price elasticity for shopping (Pai et al., 2024). This means that spending remains relatively stable despite changes in income or prices, indicating that it is becoming a necessity in their travel. When considered alongside content that normalises spending, it points to a trend of overconsumption where purchases are increasingly tied to experiences.

Influencer content is transforming overconsumption as the norm in today’s digital age. With each endorsement from these idolised personalities, they reinforce unnecessary spending by framing it as desirable, socially significant and integral to an individual’s experiences. Firstly, influencer-curated aesthetic and lifestyles dictate trendy items, often compelling followers to purchase goods that would later fade in relevance and be replaced by a new trend. It also encourages the use of certain items as a form of social signalling and expression of self-image, further increasing user consumption. Finally, content creation increasingly relies on the buying of impractical and non-essential items more than ever, particularly through prominent formats such as haul videos, where purchases and material possessions are highlighted. Thus, both influencers and users become active participants in social media-centric and performative consumption.

Before you grab your device and start scrolling away, remember – acquiring more won’t make you more.

References

Dinh, T. C. T., & Lee, Y. (2024). Social media influencers and followers’ conspicuous consumption: The mediation of fear of missing out and materialism. Heliyon, 10(16), e36387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36387

Macías Urrego, J. A., García Pineda, V., & Montoya Restrepo, L. A. (2024). The power of social media in the decision-making of current and future professionals: a crucial analysis in the digital era. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2421411. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2421411

Pai, W.-T., Phan, K.-T., Pham, C.-V., Lee, J.-M., & Hsieh, C.-J. (2024). Analyzing tourist expenditures incurred on long-, medium-, and short-haul trips to Taiwan. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 5(2), 100138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2024.100138

Riboni, G., & Ringrow, H. (2025). Unhinged consumerism or aspirational organisation? A critical discourse analysis of restock videos. Discourse & Society, 0(0), 09579265251336791. https://doi.org/10.1177/09579265251336791

Shah, D., Webster, E., & Kour, G. (2023). Consuming for content? Understanding social media-centric consumption. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113408

Wu, S. (2024). The Rise of Blind Boxes: Cultural, Marketing, and Consumer Trends Behind Bubble Mart’s Global Success. 1(10), 1-5. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.61173/nn89jm39

Zhang, T. (2025, February 20). How the Fluffy Figurine Labubu Is Catching Fire as the ‘It’ Bag Charm for Royals, Socialites and Lisa. Women’s Wear Daily. https://wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-features/labubu-bag-charm-royals-celebrities-fashion-1236847325/