Football is a sport beloved by all levels of society in Indonesia. From the narrow streets of Jakarta to the village fields in remote Papua, the game always unites people. Every national team match is always a mass spectacle: coffee shops are packed, outdoor screens in public squares are crowded, and social media feeds are filled with comments. However, despite the public’s enthusiasm for the sport, the Indonesian national team’s achievements at the international level have often been disappointing. The Junior and Senior National Teams have repeatedly suffered early exits from various tournaments in Southeast Asia and Asia.

Since joining FIFA in 1952, Indonesia has never tasted major glory at the Asian level. Even in Southeast Asia, the Garuda squad (the Indonesian National Team) has reached the AFF Cup finals six times, but has always finished as runner-up. This disappointment has truly led the public to question: when will Indonesian football be able to compete?

To address this, one of the federation’s solutions is the foreign player naturalisation strategy. This policy, implemented in the early 2000s and gaining popularity in 2010, aimed at instantly improving team quality. A number of players of foreign descent, as well as foreign players with long-standing careers in Indonesia, were granted citizenship so they could wear the red and white uniform and represent Indonesia on the pitch.

Did you know? In Indonesia, the term “football” refers to soccer, unlike the Australian Football League (AFL), which is popular in Australia and has distinct rules and culture. The game is played by two teams of eleven players each, with the goal of getting the ball into the opposing team’s goal without using their hands or arms, except for the goalkeeper. Indonesia’s domestic league, known as Liga 1, is the highest level of football competition, featuring several major clubs such as Persija Jakarta, Persib Bandung, and Bali United. This competition is primarily a platform for local players, but in recent years, it has also become more vibrant with the arrival of naturalised players such as Thom Haye (born in the Netherlands), Sandy Walsh (born in Belgium) and Jordi Amat (born in Spain), adding a new dimension to the development of Indonesian Football.

The inclusion of naturalised players has significantly influenced Indonesian football by improving team performance, increasing global recognition, and sparking debates on national identity in sports. Furthermore, federation policies and public reactions demonstrate the complexity of this phenomenon.

Many might ask, Why do Dutch people choose to play for Indonesia? The answer is simple: they are part of the Indonesian diaspora, connected by history and identity. Their decision to “return” to Indonesia through football is not just a professional move, but also a way for them to reconnect with their roots.

Enhancing Team Perfomance

The first noticeable impact has been the improved performance of the national team. In recent years, the arrival of players like Jordi Amat, Sandy Walsh, Shayne Pattynama, and several others has made the national team’s performance even more promising.

As VOI Team reports, Jordi Amat, a centre-back with Indonesian heritage through his grandmother from Makassar, South Sulawesi, who once played in the English Premier League with Swansea City, is now a pillar of the Indonesian defence. Sandy Walsh, a Belgian-born right-back with Indonesian heritage through his father from Manado, North Sulawesi, adds discipline and composure to the back line. Meanwhile, Shayne Pattynama, a player of Ambonese descent through his parents who has a career in Norway, provides flexible options in the Garuda national team’s defence and midfield.

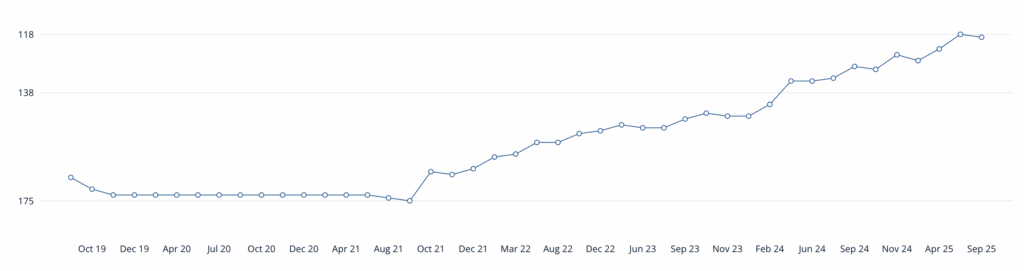

This change is beginning to be reflected in the rise in the FIFA rankings. In 2021, Indonesia fell to 173rd in the world. However, since the tenure of South Korean coach Shin Tae Yong and the arrival of many naturalised players, Indonesia’s ranking has slowly risen, with the potential to reach 120th in the world by 2025, a significant jump over the past two decades.

Besides the ranking increase, the quality of the players was also noticeably different. In the Asian Cup qualifying matches, Indonesia managed to draw or win against teams considered much stronger, such as Vietnam and Saudi Arabia. One highlight was the 2023 FIFA match day against Argentina, with their star player, Alejandro Garnacho, putting in a respectable performance. The Garuda national team held off the onslaught of the world champions despite losing 2-0.

“Indeed, if there are Indonesian players and their performance is good, they will definitely be submitted again (for naturalisation),” said Shin Tae-yong

Thus, player naturalisation clearly provides a significant boost to the development and quality of the Indonesian team, while also motivating local players to compete healthily.

Increasing International Recognition and Exposure

The arrival of several new faces from naturalised players has also brought global exposure. Several foreign media outlets have begun to take notice of Indonesia, not only because of its large fan base, but also because many players with European backgrounds have begun choosing to play for the Garuda.

Jordi Amat’s successful naturalisation in 2022 prompted several Spanish media outlets, including Marca, to write dedicated articles about his decision to change citizenship. Similarly, the citizenship changes of Sandy Walsh and Shayne Pattynama were also reported by Dutch media. Such coverage reaffirms Indonesia’s commitment to developing its football.

Beyond the media, several Indonesian matches are also increasingly in the spotlight. For example, when Indonesia hosted Argentina, foreign media not only highlighted the absence of Argentine star Lionel Messi but also highlighted Indonesia’s courage in facing the world’s number one team. This demonstrates that the emergence of new European faces in the Indonesian squad is increasingly attracting attention abroad.

In line with this, in the era of sports globalisation, media and transnational networks have made sporting achievements not just about victories on the field, but also about how a nation’s story and image are told to the world. According to David Hassan, countries that were previously less well-known on the international stage often use sport to expand global recognition. In the case of the Indonesian national team, this strategy is seen when naturalising players not only strengthens the team’s technical quality but also provides an opportunity for Indonesia to be more globally highlighted for its football. Thus, this naturalisation policy has a dual function: improving the quality of the game and strengthening Indonesia’s image in the eyes of the world through sports diplomacy.

Debates on National Identity and Fairness

While the presence of naturalised players has had a positive impact, this phenomenon has also sparked debates about national identity and fairness. As highlighted by Rafi Pasha, many have questioned whether players born and raised abroad, and only now holding Indonesian passports as adults, truly represent Indonesian identity. Some observers believe that naturalisation undermines the hard work of local players who have grown and developed from small academies with limited facilities. Former national team player Ponaryo Astaman once stated:

“Naturalisation should not be the only way. This is the last route that should be chosen,” said Ponaryo Astaman.

A closer look at other countries’ experiences with naturalisation suggests that perceptions can be more complex. For example, naturalised players in the Hong Kong national team can enrich the team through international skills and experience, while also serving as symbols of social inclusion and contributions to local culture. Yung, Chan and Philips argue that naturalisation is not always perceived as diminishing national identity, but rather can strengthen national identity through tangible integration.

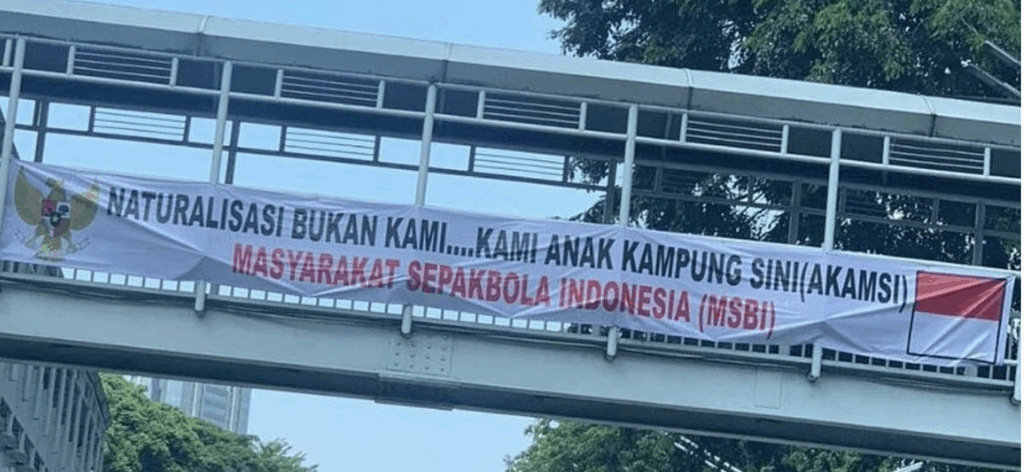

A similar debate has emerged in Indonesia, with some fans emphasising the importance of developing local players. Some supporters have even erected large banners on Jakarta’s main roads that read: “Naturalisation is not us…. we are village children here” – Indonesian Football Community. This debate ultimately touches on a deeper issue: what does it mean to be Indonesian in football? Is it determined by blood, culture, or a willingness to serve? There is no single answer, and that is precisely where the complexity of this phenomenon lies.

Policy and Governance in Indonesian Football

Understanding who Indonesia is as a nation also means acknowledging its complex colonial past and the global footprint of its people. The story of football naturalisation reflects this broader identity shaped by migration, heritage and postcolonial ties. This naturalisation is inextricably linked to the federation’s policies and national politics. From the beginning, the PSSI (Indonesian Football Association) has targeted players of Indonesian descent, particularly those born in the Netherlands. This is because more than three centuries of Dutch colonial rule left a legacy of the diaspora. After independence, many families of Indonesian descent settled in Europe, particularly the Netherlands, providing their generation with modern football education.

Modern Diplomacy states that the Indonesian-Dutch diaspora carries a hybrid identity that reflects Dutch and Indonesian cultural roots, and that the naturalisation of these descendants is not just a sporting strategy, but also part of cultural diplomacy and historical reconciliation.

A real-life example of this occurred in the 2025 Indonesian national team squad, where 10 of the 29 players in one squad were Indonesian-trained, while the rest were of Dutch descent or naturalised from abroad. Jay Idzes, the Indonesian national team captain, who was born and raised in the Netherlands and hasIndonesian heritage through his grandfather from Semarang, Central Java, stated that despite this, he felt a “duty” to represent Indonesia. Jay Idzes state that the naturalised players had integrated well into the group, demonstrating that the adaptation process within the PSSI policy framework was effective.

Based on this, the naturalisation procedure reflects how the PSSI views diaspora players not as an emergency option, but as part of a strategic vision to build a team capable of competing at the Asian and even global level. This is closely related to government regulations, as the process of granting citizenship to foreign athletes requires the approval of the House of Representatives (DPR) and is ultimately ratified by a Presidential Decree. However, a gap remains in governance regarding whether local player development should be strengthened to avoid complete reliance on players of mixed descent.

Fan Culture and Public Reactions

Known as one of the countries with the largest football fan bases in the world, it’s no wonder that Indonesia’s naturalisation policy immediately sparked mixed public reactions. On social media, photos of Ole Romeny, a forward with Indonesian heritage through his grandmother from Medan and Joey Pelupessy, a midfielder with Indonesian heritage from Maluku, Indonesia’s newest naturalised players, garnered hundreds of thousands of likes, wearing red and white jerseys. Many fans expressed pride that players with European careers were willing to represent Indonesia. Expressions like “finally the national team has a world-class player” frequently appeared in the comments section of the Indonesian national team’s official Instagram account.

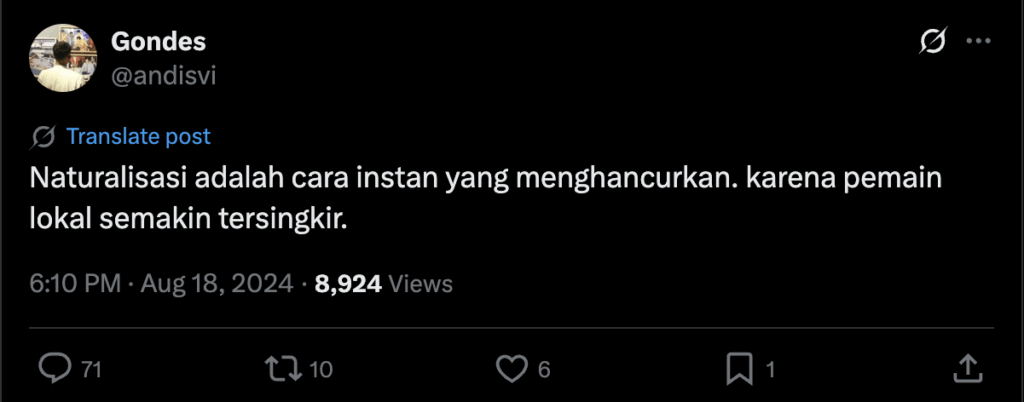

However, the criticism that emerged was no less harsh. Some considered naturalisation merely an “instant shortcut.” Some supporters even compared it to the presence of local players. One user, X, wrote: “Naturalisation is a destructive, instantaneous method, as local players are increasingly being pushed aside.”

Interestingly, responses also differed across regions. In large cities like Jakarta or Bandung, the majority of fans were more open to naturalisation due to their familiarity with global culture. Meanwhile, in more remote areas, some were more sceptical and emphasised the importance of developing local talent. However, once in the stadium, the voice of support remained dominant. When Ole Romeny first appeared in Jakarta, supporters sang a special chant to welcome him, the lyrics of which were “ole ole ole ole.” This shows that for most fans, the struggle on the pitch is more important than the player’s origins.

The phenomenon of naturalised players has brought about significant changes in Indonesian football. Performance-wise, the Garuda squad has become more formidable and competitive. Meanwhile, international exposure has increased, leading the world to take notice of Indonesian football. However, on the other hand, a long-running debate has emerged regarding national identity, fairness for local players, and the future direction of Indonesian football development.

Naturalised players have strengthened teams and increased global recognition, but have also sparked identity controversies. Historically, the presence of many players of European descent, particularly Dutch descent, demonstrates how colonial legacies still resonate in modern sports. While this presents an opportunity for Indonesia to harness diaspora talent, it also presents challenges in developing domestic strength.

The future of Indonesian football will be determined by the ability to balance short-term strategies through naturalisation programs with long-term development through youth development. Naturalisation can provide an instant boost, but it’s not the only option.

Through a combination of the right strategy, extraordinary support from fans, and the long-term vision of PSSI, it is not impossible that one day Indonesia can truly go further, not only becoming the king of Southeast Asia, but also competing in the Asian Cup and even the World Cup.