Indigiverse is the world’s first Aboriginal and all Indigenous Superhero Universe, created by Gooniyandi writer Scott Wilson. In the Indigiverse, superheroes draw their power from the Dreaming or spirit world. Since 2023, four comics have been released by Indigiverse. Dreamwalker is the fourth and latest release. Following the journey of Mungala, the matriarch of Indigiverse, who traverses time and space between northwest of Western Australia and beyond. All three Dark Heart comics were written by Wilson alone, however, given that Dreamwalker is about a matriarch it feels appropriate that Wilson has collaborated with Balanggarra and Yolngu artist, Molly Hunt. Editor Wolfgang Bylsma and Worrorra artist Christopher Wood bring together the vision of Wilson and Hunt with clarity and intention.

Image: Dreamwalker cover by Christopher Wood via Indigiverse

The story of Dreamwalker “pays homage to the strength of our women and the matriarch system of the Gooniyandi people.” written by Scott Wilson and Balanggarra and Yolngu artist, Molly Hunt. But it’s also a very personal story. Not only does it draw on Wilson’s own experience of growing up away from Country, the heroine Mangala is inspired by his great-grandmother. For those who are unaware, Gooniyandi people are custodians of Country across the Kimberly region in Western Australia, covering 11,173.9135 km² of land and water. Bound by the “Margaret River, Christmas Creek and the Great Sandy Desert in the South, and the Fitzroy River to the west” according to the Gooniyandi Aboriginal Corporation.

I first came across Dreamwalker through meeting Scott Wilson at a symposium about temporality called No space is empty, produced by the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney in June 2025. I was instantly intrigued by the premise of the story, and after finding it was sold out at comic stores in Sydney, promptly ordered some copies from Western Australia to my home in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa.

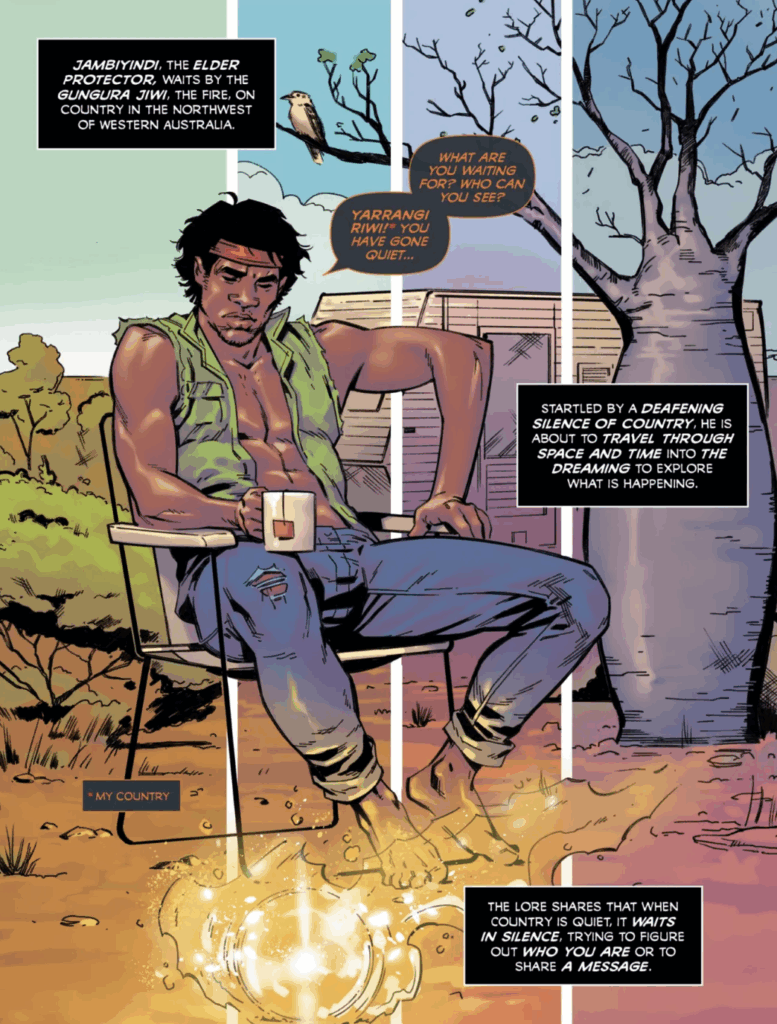

My first impression of our heroine, Mangala, is the front cover where she strikes a power pose mid air with a shield in one hand and an electrical life force emanating from the other. Surrounding Mangala is a series of characters that you will meet throughout the comic, including another protagonist named Jambiyindi. A striking similarity across the series is the opening scene where we meet an elder, in this case Jambiyindi. On first look, Jambiyindi doesn’t look like an elder at all. He is a fit, muscular young man maybe in his early twenties.

Image: Dreamwalker by Scott Wilson and Molly Hunt, illustration by Christopher Wood via Indigiverse

Throughout the comic, Wilson and editor Wolfgang Bylsma use different font colours and speech bubbles to differentiate between English and Gooniyandi, context and dialogue. White text inside a black rectangular box offer story context in English, whereas orange text inside speech bubbles offer dialogue and orange text in a black box offered translations (where needed). As someone who is not used to reading bi-lingual comics, it took me a while to adjust to this style of story design, as it required looking around the entire page. Though I found this frustrating at first, I appreciated that it forced me as a reader to take in the entire image, and to be an active reader.

At the beginning of the story, Jambiyindi is sitting by a fire when he feels something in the Dreaming stirring, calling him. We cross to see Gooniyandi people come into contact with Aliens who want to take a warrior from Gooniyandi people. Upon first landing, the alien technology scans Country and detects no technology “just flora, fauna, stocks, stones.’ The alien’s super intelligence has the ability to speak in Gooniyandi, which is disarming for Mangala’s father. After being confronted by a pregnant Mangala, the aliens recognise her warrior spirit, zap her and kidnap her. At this point, Jambiyindi’s spirit leaves his physical form and traverses the Dreaming to save Mangala. He brings her back to life by summon the ochre of the dreaming, which can be summoned by elder protectors only. Mangala wakes, having given birth to her child, but the baby is taken by a cyborg. Whilst trying to escape, Mungala realises she can now understand the alien language, finds a weapon and battles the aliens again in the name of finding her child. She steals a spaceship, lands back in Gooniyandi Country only to find her father is dying. He gives her his shield, sending her to painted rock to “become our shield/protector!” Aliens find her, following Mangala into painted rock, and she promptly places her blood covered hand onto the walls, transporting her into the Dreaming and the consciousness of a young woman. And so we are well positioned as an audience for the next chapter.

As a mother, I was initially struck by the fact that Mangala was suddenly pregnant onboard the Alien spaceship, and that her child was immediately taken. I felt confused by the immediacy – perhaps as I’m not used to how time works in comic worlds – but also why the grief of losing a child was part of Mangala’s narrative. However, after reading this interview with Scott Wilson, I learned that his grandmother (the daughter of great-grandmother, Mangala) was part of the Stolen generation.

Image: Dreamwalker by Scott Wilson and Molly Hunt, illustrated by Christopher Wood via Indigiverse

When speaking to NITV, Wilson encapsulates his universe as, “The Indigiverse is all about the oldest living cultures inspiring the newest living superheroes.” You get this sense throughout the comic, as you see the Dreaming allows people to leave their physical form and travel to other dimensions. I particularly love and am inspired by the fact that kinship and earth elements transform into both superpowers and temporal weapons for Mangala and Jambiyindi. It aligns with global Indigenous notions of time being non-linear. Encapsulated in their essay, ‘Does Māori Art History Matter?” Professor Deidre Brownn (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu), Ngarino Ellis (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou) and Jonathan Mane-Wheoki (Ngāpuhi, Te Aupouri, Ngāti Kuri) propose that in Te Ao Maori (The Māori worldview),

“The past, or future for that matter, can be above, below, close, distant, or facing towards or away from us or you, depending on the situation or subject.”

Dreamwalker was my introduction to First Nations comics. At times it felt difficult to follow the narrative, due to the design and complex layers of narrative, temporal devices and bi-lingual dialogue, but I enjoyed and welcomed the challenge to how I usually receive and interpret information. As someone with a personal interest in Indigenous temporalities, I was fascinated by this medium as a means of communicating and preserving cultural knowledge for the Gooniyandi peoples and inspired to think about how this could be a tool for my own peoples.