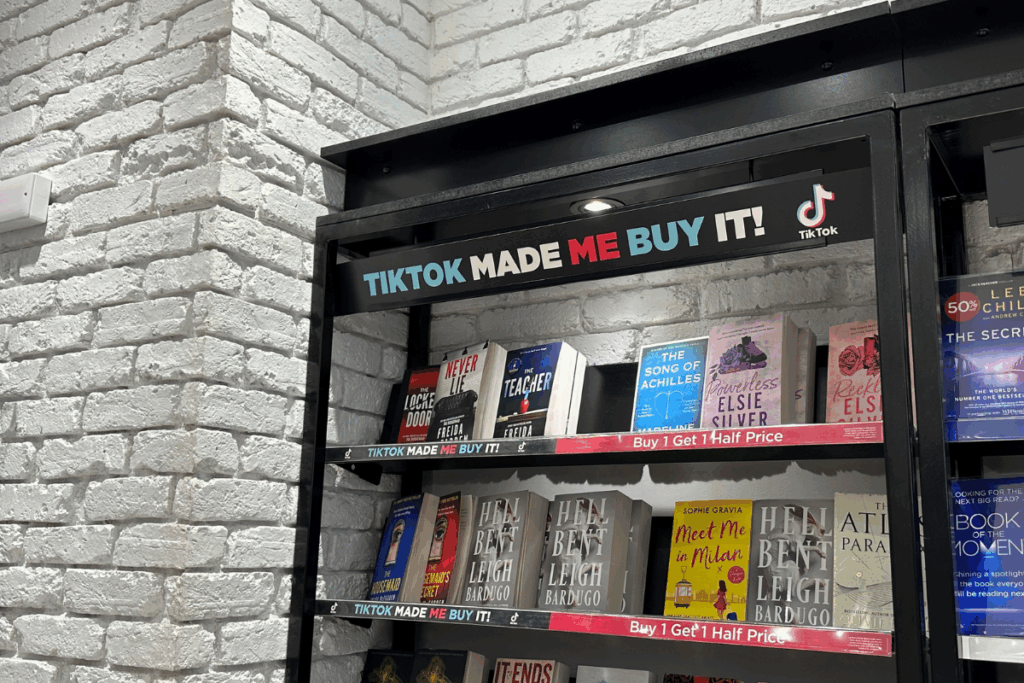

“God Tier 6 Star Books”, “Popular BookTok books I didn’t like”, and “Books with smut that will make you sweat” are, at the time of writing, three of the top trending book-related TikToks. Beautiful book covers, colour-coordinated annotations, emotional or hyperbolic language such as “[books] that have altered my brain chemistry”, aesthetic shelfies, and trending audio tracks are all vital ingredients that contribute to the BookTok shortform video. These videos have the power to take a book from obscurity, from the dusty, often forgotten about bottom shelves, and catapult them into the glamorous world of a BookTok hyped book. There is no doubt that while the TikTok subgenre BookTok has positively influenced reading habits, by broadening readership and relationships it has simultaneously also narrowed exposure to diverse content and enclosed readers into repetitive echo chambers.

TikTok originally rose to popularity particularly with Generation Z (Gen Z), due to it being the less curated and filtered social media application, differentiating itself from its polished counterpart Instagram (Jerasa & Boffone, 2021). Jerasa and Boffone (2021) describe TikTok as a space where the app has taken the best features from many social media applications, combining them into one where users can easily find their community. The application allows users to upload short-form video content as well as interacting with other users and their content. BookTok is a community on TikTok which shares content related to books. Content such as snappy book reviews, emotionally fuelled reading lists, extensive book hauls and aesthetic bookshelf tours are typically enjoyed on BookTok.

Through the thriving community of BookTok we have seen a global increase in those reading and enjoying the joys that books can bring to an individual. Jerasa and Boffone (2021) explore the positive impact that BookTok has on school-aged readers suggesting that the app offers similar interactions to readers as a classroom environment, including book discussions and book presentations leading to community building among peers. The authors suggest that readers become more engaged and are likely to pursue ownership of their own reading (Jerasa & Boffone, 2021). Engaged readers are more likely to read widely, encouraging better “reading comprehension” and “textual understanding” (Jerasa & Boffone, 2021). This seems beneficial to creating “engaged” or even “avid readers” as it is giving contextual skills to various reading abilities and is not a simple, blanketed transfer of information from educator to student (Jerasa & Boffone, 2021; Wright et al., 2025). Jerasa and Boffone (2021) proceed to highlight the ways in which BookTok provides diverse recommendations, is a form of digital literacy in itself, and then suggests ways in which educators can incorporate the app and its various affordances into the classroom. These points suggest that BookTok can be used as an effective tool for students and adults alike, they just need to be shown mindful ways of using it.

Asplund et al. (2024) also explore the positive impact that BookTok has on reading habits. The authors initially note the previous decline in voluntary reading, the current shape of the reading culture in Sweden and follow with how BookTok is enhancing younger readers’ lives. The results of the study found that BookTok users enjoyed feeling part of a community and being offered a sense of belonging (online and offline), a place for conversation and discussion, book recommendations based on emotions instead of content, receive an insight to reading practices and routines, and offered an identity (Asplund et al., 2024). This demonstrates that BookTok offers a safe space for readers to engage in where previously they may not of as book review spaces were often academically focused or elitist.

While BookTok does encourage positive reading habits within the community, users are encouraged to be mindful of the echo chambers created by social media algorithms, the authenticity and fulfilment power of online communities compared to traditional communities, as well as the impact that BookTok is having on the publishing industry. Filter bubbles originally observed in search engine algorithms and now social media algorithms, while not new territory in the web-sphere, is still an area not consciously considered by everyday users (Pariser, 2011). Reddan et al. (2024) comment on how the recommendation algorithms found on BookTok, lump readers into categories where they are not commonly shown content outside of these categories. The authors also comment on the implications of publisher’s being so connected to readers. Implications including sending Advanced Reader Copies to content creators to be shared in hauls and reviews or using consumer input to dictate what is being published. Reddan et al. (2024) do note that this can be positive as observed in sharing diverse voices.

Maddox and Gill (2023) discuss the “imagined communities” established in various corners of the web such as BookTok. Part of the study assesses the “recommendation” video strengthening bonds in “imagined communities” where the contents of the TikTok video along with hashtags and the apps algorithm, will recommend videos with similar content. The authors suggest that this type of content coupled with the algorithm inflates how much a book is liked or disliked. This provides an illusion to readers, publishers and authors of what type of books are considered popular in that moment.

While it is indisputable that BookTok has positively influenced reading habits globally, some of the broader implications cannot be ignored such as the impact on communities, the “choke-hold” of the echo chamber, and the wider impact on the publishing industry. Jerasa and Boffone (2021) and Asplund et al. (2024) both offer insight into the positive ways in which BookTok is influencing reading habits. Shortform videos offering book recommendations, showing book hauls or touring bookshelves can be an encouraging and engaging way to get consumers excited for specific titles or the act of reading in general. A significant positive for the vast BookTok userbase is that there are many different creators to suit different readers. Creators will have varied aesthetics, video styles, book taste and reading habits that will likely only appeal to certain viewers. Malissa (@bewareofpity), posts Book reviews mostly for Literary Fiction books where her style is fairly understated and her TikTok’s are mostly her speaking to the camera without trending audio tracks. Miranda (@probablyoffreading), on the other hand posts book content mostly of the romantasy genre and is more upbeat, where her style is to be a little more performative and creates trending content. While these two creators offer very different book related content, both are very successful on the platform with hundreds of thousands of subscribers respectively. Each creator seems to have a positive influence on those consuming their content as users are reading or purchasing the books recommended by them, according to the comments sections. While these are positive implications that BookTok has on readers it would be misleading to not comment on the addictiveness that this content has, encouraging users to continue scroll through content. Interaction between creator and consumer can also offer a form of community which commentators have regarded as a positive and negative aspect.

Jerasa and Boffone (2021), Asplund et al. (2024) and Maddox and Gill (2023) each provide commentary on the virtual community created between creator and consumer, and also consumer and consumer, within comment sections or dedicated spaces on other applications such as Discord or Reddit. Maddox and Gill (2023) specifically comment on imagined communities and communities formed through algorithmic recommendations. When researching for their paper Maddox and Gill (2023) created a new TikTok to join the BookTok community and were initially recommended white, female creators’ content due to the platform’s assumptions about the user without any pre-existing data. One could imagine this could be irritating or even hurtful to those who belong to differing communities, identify differently or wish to see more diverse content.

Users, whether they are creator or consumer, are also able to create an edited or curated presence which could contribute to being an inauthentic member of the digital community. This can be done on their profile, in video content and through post engagement. It is understandable that users can feel the need to only show a portion of their personality with the way in which internet culture is quick to cancel users who appear to have differing opinions to the majority of the group. It also doesn’t help that these platforms can save a historical record of everything a user has every commented or posted throughout their entire existence on a platform which doesn’t always allow for personal growth or context to be regarded (Boyd & Papacharissi, 2011). A positive way in which BookTok can influence community is when groups are formed or expanded upon in real life. Sharing book recommendations from a creator with friends, colleagues or peers and discussing the creator or books recommended can help strengthen traditional community where context is more easily transferred.

A significant area of concern is the echo chambers or filter bubbles established on TikTok that are influencing BookTok community members. The purpose of the social media algorithm is to keep you engaged with the application i.e. to continue scrolling. The way social media applications do this is by tracking previous content you have interacted with by means of searching, commenting, liking and sharing, and using this to show you more content that is similar. This could be a book title such as “Throne of Glass”, an author such as “Sarah J. Maas”, or even a genre such as “romantasy”. This engagement history will then contribute to what you will likely be recommended by TikTok in future such as books and series similar to the Throne of Glass series, more Sarah J. Maas content, etc. This recommendation system can then place BookTok users inside a “filter bubble” or “echo chamber”, not diversifying the content that is recommended to them (Pariser, 2011). This is such a shame when there are so many books out there to read and so many voices out there to be heard, outside of the same continuously trending books (Reddan et al., 2024).

Some users have grown savvy to this system and are trying to diversify their feeds using hashtags such as #readaroundtheworld, #translatedfiction, #womenintranslation and #diversebooks. Creators celebrating diverse reading months such as “Women in Translation (August)”, “Black History (February)”, and “Pride Reads (June)”, are great examples of creators expanding their own reading while also using their following to generate positive reading recommendations and goals within their community. Malissa (@bewareofpity), is creator who does this well referencing authors from around the world in her general monthly recaps or with specific recommendations to diverse authors such as Women in Translation. Her TikTok post on her current favourite reads for 2025 references authors such as James Baldwin (United States), Aysegul Savas (Türkiye), Marlen Haushofer (Austria), Bell Hooks (United States), Georges Bernanos (France), Vincent Delecroix (France), Fyodor Dostoevsky (Russia), Benito Pérez Galdós (Spain), Ivan Turgenev (Russia), Barbara Comyns (United Kingdom), and Magda Szabo (Hungary).

Reddan et al. (2024) comment on the influence that these echo chambers have had on the publishing industry as it is very easy to conflate the popularity or rejection of a book, series or author. Publishers can use these “statistics” and trends to their advantage, publishing titles or authors that are similar to those that are trending. This has been positively beneficial to the world when readers were calling for more diverse titles to be published for example around Pride Month for more LGBTQI+ characters or around Black History Month when asking for more books by BIPOC or featuring BIPOC characters and stories. We are now seeing these titles published far more regularly not only just around these significant months. Publishers are also harnessing the influence of the content creator and their audiences by sending them Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs), pre-release date to be featured within a haul or reading vlog, generating publicity and hype. While this is smart marketing, it comes across a little bit inauthentic when creators are including it in videos with books, they have also purchased themselves. A concerning repercussion of publishers printing what is currently trending is what impact this has on authors and is this changing what authors are writing about. Of course, it is positively impactful if what the author is writing falls under what is trending at the time, however, what about those who don’t, how are they now being discovered? Thankfully, with the various different types of BookTokers there is an opportunity for a vast collection of books to be shared and hyped.

BookTok has solidified itself as prominent cog in the TikTok machine. It has the power to help reading flourish, especially in the younger generations where it was slowly decaying. A space that offers varied reading recommendations, an inclusive space to build inclusive and diverse communities, and foster relationships between authors and readers are all highly positive experiences enhanced by TikTok. Complex challenges needing to be addressed include the lack of in-person community, inauthentic representation of self, and the echo chambers preventing users from diverse titles while also shaping the publishing industry to only print more of what is trending. While these are complex challenges it would be a disservice to not attempt to positively change them as TikTok has been vital in boosting an indisputable uptake in readership.

References

- Asplund, S.-B., Ljung Egeland, B., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2024). Sharing is caring: young people’s narratives about BookTok and volitional reading. Language and education, 38(4), 635-651. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2024.2324947

- Boyd, D., & Papacharissi, Z. (2011). Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications. In (pp. 47-66). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876527-8

- Jerasa, S., & Boffone, T. (2021). BookTok 101: TikTok, Digital Literacies, and Out‐of‐School Reading Practices. Journal of adolescent & adult literacy, 65(3), 219-226. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1199

- Maddox, J., & Gill, F. (2023). Assembling “Sides” of TikTok: Examining Community, Culture, and Interface through a BookTok Case Study. Social Meida + Society, 1-12.

- Malissa. [@bewareofpity]. (n.d.). TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@bewareofpity

- miranda 🎀. [@probablyoffreading]. (n.d.). TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@probablyoffreading

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble : what the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press.

- Reddan, B., Rutherford, L., Schoonens, A., & Dezuanni, M. (2024). Social Reading Cultures on BookTube, Bookstagram, and BookTok (1 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003458616

- Wright, B., Lennox, A., & Mata, F. (2025). Understanding Australian Readers : behavioural insights into recreational reading. https://australiareads.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Understanding-Australian-Readers-Full-Report.pdf