At what age did you first download social media? Was it during your first year of high school, directly from primary school, or even earlier? A study by the University of Sydney found that for the majority of young Australians, the answer is people aged between 12/13 (typically when they enter high school), the time when everyone suddenly has a phone and the pressure to connect is unavoidable, (New Study Reveals Teenagers’ Social Media Use and Safety Concerns, 2023). I still remember downloading my first app at that age, not because I was particularly interested in the platform, but because my peers were already using it. The thought of being left out or excluded felt unbearable. My parents objected, of course, they introduced strict household rules- my phone was confiscated after school and returned only the next morning. Was it annoying? At the time, yes, but in hindsight, those limits provided balance through my teen years.

Fast forward to 2025 and the Australian government has introduced new legislation banning social media use for anyone under 16. Under the new rules, platforms that allow underage users risk steep financial penalties. The law applies not only to new users but also to existing accounts owned by children under 16. Age verification requirements, stricter privacy protections and fines for non-compliance all part of the rollout but how would this work in practice? The government has shared the apps will not be able to demand government ID as a sole proof of age, yet the alternative methods are not clear. Biometric systems such as facial recognition technology have been suggested, but raise significant privacy concerns.

On the surface, this policy is driven by good intentions: protecting children from cyber bullying, grooming, harmful content and the mounting evidence of social media’s impact on mental health. But critics argue that the policy risks creating new problems. If teens are banned from main stream social media, will they simply migrate to less regulated online spaces? Could the ban isolate Australians young socially disrupting the development and limiting access to vital resources? While the government is prioritising protection, the real world impact on teens may be more complex than intended.

They say: The Case for Protection.

The Australian government has framed the new legislation as a child protection measure. In it’s 2025 fact sheet on social media minimum age, the government stated that the age ban is designed to “protect young Australians from pressures and risks that users can be exposed to while logged into social media accounts” (Department of Infrastructure, 2025). The legislation explicitly defines “age restricted social media platforms” as services whose primary purpose is enabling interaction between users and content sharing.

The penalties for non-compliance are significant. Platforms that fail to enforce the ban could face hefty fines. This approach reflects a broader global concern that children and teenagers are spending more time online than ever before, and the exposure to harmful content is real. The eSafety Commissioner has been at the forefront of arguments supporting the legislation. According to the commissioner’s office, children are at risk of cyber bullying, online grooming and exposure to violent or sexually explicit material. Reported harms include increasing anxiety, sleep disruption and decreased mental well-being among young users (eSafety Commissioner, 225). These concerns are not abstract. Australian parents frequently report distress over their children’s online experiences, pointing into harmful encounters in chat rooms peer pressure and image based platforms and relentless advertising targeted at youngest audiences.

From the above perspectives, it is clear that the age ban is a preventative measure. Just as Australia has laws around alcohol and tobacco consumption, policymakers argue so too should the country regulate access to social media by raising the digital “age of entry.” The government hopes to create a safe environment for young people to grow without undue digital pressures.

Others Say: The Case Against Age Bans.

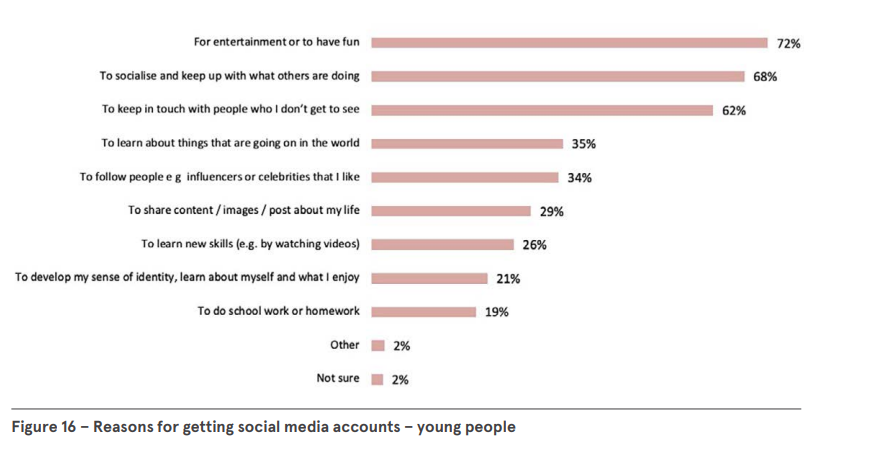

Critics of the legislation argue that age bans risk doing more harm than good. One of the most consistent concerns raised by academics, advocates and young people themselves is that such laws could isolate teenagers socially and stunt their digital literacy development. Social media is not just a platform for distraction; it is also a tool for connection, creativity and learning. The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY, 2023) has highlighted the importance of balanced digital engagement, noting that many young people use spaces to find support networks, build identity and engagement in their social life. Cutting them off entirely could mean removing vital lifelines or support systems.

Digital media researcher from Curtin University, Tama Leaver, has gone even further into questioning the practical impact of the ban in an interview with ABC in 2024. Where he argued that blanket restrictions are unlikely to work in practice because age verification is easily circumvented. Children and teens have long found ways to access restricted platforms, whether through false birthdates, shared accounts or new and anonymous profiles. According to Leaver, this creates an environment where the law is out of step with digital realities, pushing young people towards secrecy rather than safety. His comments share a key criticism, regulation that does not reflect how young people actually use technology may dissolve trust in both government and institutions.

There’s also the matter of evidence, while policymakers often point to research suggesting a link between social media and poor mental health, studies do not present a uniform picture. A Curtin University 2025 study recently challenged assumptions about the harm caused by online platforms, suggesting that social media can have neutral or even positive effects when used in healthy ways. This adds weight to the argument that a ban is blunt, targeting the medium rather than behaviours or contexts that truly shape well-being.

Young Australians themselves have voiced nuanced views on the matter. A study on youth perspectives revealed that while many are concerned about mental health, they also recognise that digital technologies are embedded in their everyday lives. Rather than calling for outright bans, young people in the study demanded action on broader systematic issues, such as mental health support services and education reforms that might more effectively address the cause of distress. This suggests that a ban may misrepresent or oversimplify the actual needs and concerns of the demographic it aims to protect.

Furthermore, critics are arguing that more effective alternatives might involve education co-regulation with industry and parental guidance, rather than prohibitions. Advocates for digital literacy programs suggest empowering young people to critically engage with technology is more sustainable than restricting access. By teaching students how to identify misinformation, manage screen time and seek help when needed, society could create resilience rather than independency.

Taken together, these perspectives frame the age ban as an overly simple solution to a complex problem. Opponents stress that while online harms are real, they require nuanced, evidence based responses rather than restrictions that could leave young Australians disconnected and unprepared for the digital world they inevitably must navigate.

I say: The Reality of Consequences.

The intentions behind the band are commendable, social media can be harmful and proactive protection is worthwhile. Yet when we dig deeper, the legislation’s flaws, and unintended consequences become clear.

One: Social and Emotional Impact.

Adolescence is a period defined by peer connection. Denying teens access to the digital spaces where their friends interact risks social exclusion. In today’s world group chats, memes and online communities are integral teen social life. Research found that digital engagement is essential to young Australian’s sense of belonging and identity. To ban access is to restrict their social development and potentially worsen feelings of isolation.

Two: Educational and Development Consequences.

Social media is not solely impractical. Platforms like YouTube are used for tutorials, learning communities and even school related collaboration. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, social media served as an essential tool for peer to peer and learning classroom communication. ARACY highlights that removing these opportunities could delay skill building and digital literacy skills which are essential for future workplace and citizenship.

Three: Workaround and Enforcement Issues.

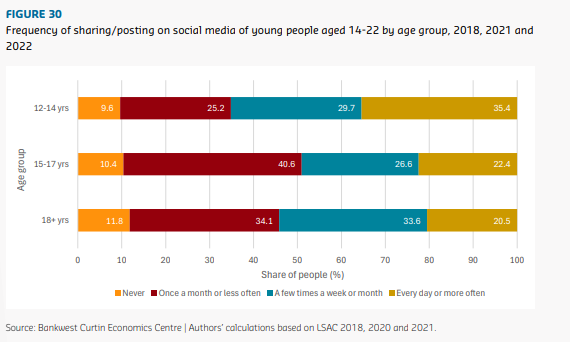

The practical enforcement of this policy is questionable. Teens are tech savvy, they already bypass existing age restrictions with little difficulty. Platforms like TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram already prohibit users under 13, yet AMCA (2020) shared in their report that 70% of children aged between 6-13 have accessed social media, with 53% of those accessing it with their own phone. The introduction of new verification systems risk creates new privacy issues. Do we really want tech giant storing biometric data on millions of Australians? If enforcement is weak the ban risks being symbolic rather than effective.

Four: Driving Teens Towards Unregulated Spaces

Perhaps the greatest unintended consequence is displacement. If teens cannot access mainstream platforms with at least some motivation, they may flock to lesser known and unregulated apps. The risks there are potentially worse. Platforms without content moderation, community standards or safety tools could expose teens to even more harmful material. This concern has been raised by experts such as Tama Leaver who told ABC Radio Perth, that blanket bans are unlikely to work and may push kids into riskier digital concerns.

Alternatives Beyond the Ban

If the goal is truly to protect young Australians, perhaps the answers lie in education and regulation rather than prohibition. France has introduced a system requiring parental consent for under fifteens to create social media accounts. A compromise that acknowledges teen social needs while giving parents a role and oversight. Similarly, ARACY recommends investment in digital literacy programs teaching young people how to navigate online risk safely.

Other alternatives could include:

- Co-regulation with social media companies to enforce stronger moderation standards.

- Mandatory online safety education in schools just like road safety is taught.

- Encouraging parental engagement rather than state imposed bans.

These solutions recognise that the digital world is not going away, rather than attempting to delay access until 16. It may be more effective to guide towards safe and healthy engagement from the start.

The government‘s new social media band for under 16 comes from legitimate concerns about safety, privacy and well-being. Cyber bullying, grooming and harmful content are pressing issues that deserve action. Yet whilst the intent is commendable, the ban might do more harm than good by isolating young people, stunting digital literacy and driving them toward unregulated spaces. The policy risks unintended consequences that out the benefits of protecting young Australian’s. Online protection does not always have to mean prohibition instead of blanket bands. Policy makers should pursue evidence based approaches that balance digital safety with social development ,education, digital literacy, parent involvement and stronger platform accountability. In the end. The question is not whether a young Australian should be online, but how you prepare them to be there safely.

Reference list

ABC. (2024, May 7). Tama Leaver says social media ban unlikely to work [Radio broadcast]. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/perth-mornings/tama-leaver-social-media-ban-unlikely-to-work/104629656

Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. (2025). Aracy. (2025, October 3). ARACY’s young and wise roundtables. ARACY. https://www.aracy.org.au/young-and-wise-roundtables/

Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2025). Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones | ACMA. ACMA. https://www.acma.gov.au/publications/2020-12/report/kids-and-mobiles-how-australian-children-are-using-mobile-phones

Childhood in a digital world. (2025, June 1). Innocenti Global Office of Research and Foresight. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/childhood-digital-world

Curtin University. (2025, February 12). New study challenges social media’s mental health impact [Media release]. Curtin University. https://research.curtin.edu.au/news/new-study-challenges-social-medias-mental-health-impact/?type=media

Curtin University. (2025, March 3). Young Australians demand action on mental health, cost-of-living, and education reform [Media release]. Curtin University. https://www.curtin.edu.au/news/media-release/young-australians-demand-action-on-mental-health-cost-of-living-and-education-reform-report/

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts. (2025). Social media minimum age fact sheet. Australian Government. https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/social-media-minimum-age-and-age-assurance-trial-fact-sheet-july-2025.pdf

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts. (2025, October 15). Social media minimum age. https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/media-communications/internet/online-safety/social-media-minimum-age

eSafety Commissioner. (2025). Protecting children online. Australian Government. https://www.esafety.gov.au/

Jones, C. N., Rudaizky, D., Mahalingham, T., & Clarke, P. J. F. (2024). Investigating the links between objective social media use, attentional control, and psychological distress. Social Science & Medicine, 361, 117400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117400

The University of Sydney. (2023, September 20). Emerging Online Safety Issues: Co-creating social media with young people – Research Report. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/31689