Stardew Valley is a cozy farming game. Created by Eric Barone, also known as ConcernedApe, the game was released on Steam on February 27, 2016, and has sold over 41 million copies across various platforms in the eight years since its release.

On the surface, the game may appear to be a wholesome, nostalgic pixel world of comforting music, friendly neighbours, and simple daily routines. It is also often praised as a relaxing place that helps players retreat from the harshness of modern work and the economy. However, beneath the game’s tranquillity lies something more hidden and complex. Stardew Valley does not simply provide escapism. It presents players with a very specific fantasy of how capitalism could be made fair, rewarding, and humane.

Stardew Valley promotes an idealised version of capitalism where labour always guarantees rewards, resources are endlessly abundant, and monopolistic corporations can be resisted or challenged. Therefore, these aspects create a dream-like economy for players, where alienation disappears, work is fulfilling, and fairness is guaranteed. By examining the game’s mechanics, storyline, and aesthetics, we can see how Stardew Valley reimagines capitalism, not by outright rejecting it, but by offering a more fulfilling version of the capitalistic system. This softer version acts as an apologia, using comfort and leisure to “play-wash” the very economic structures it critiques.

Game Mechanics

Stardew Valley begins with the player inheriting their grandfather’s run-down, abandoned farm on the edge of a small town called Pelican Town. The task is simple: restore the farm and integrate into the Pelican Town community. Each in-game day, the player can choose how they want to spend their limited time and energy. They have the option to plant crops, raise animals, mine for ores, fight monsters, forage in the woods, or even fish in rivers, lakes, or oceans. Besides that, the game features realistic characteristics with each season shaping what crops can be grown and what fish will be found, thus encouraging players to plan ahead while upgrading their tools, which allows them to work more efficiently.

The economy of Stardew Valley revolves around production and exchange. The items players gathered through labour, understood as human work or effort shaped by and connected to the relations of production, can be dropped into a shipping bin. Overnight, the bin magically converts them into gold, the game’s currency. Stardew Valley is an open-ended, constant cycle of work and reward with no strict win condition. Players have free rein to define their own version of success. Some players may focus on restoring the old Community Centre or gathering resources to complete quests, while others dedicate their time to building relationships, collecting rare items, or simply beautifying their farm. Therefore, different players may have varying amounts of time to reach a specific event in the storyline, making each gameplay experience unique for each player.

Stardew Valley also places a heavy emphasis on community. Players can befriend, date or marry townsfolk, attend seasonal festivals, and gradually become the central part of Pelican Town’s community. With no “end” in sight, the game thrives on a gentle cycle of daily labour, harvest and expansion, which creates a rhythm that feels productive and replayable.

Storyline and capitalism

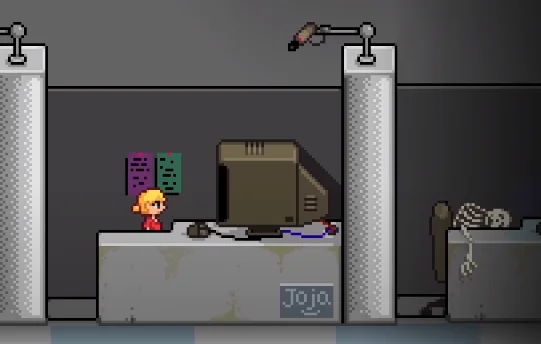

The game opens with a cutscene that shows the player trapped in their grey cubicle when working at Joja Corporation. The office is filled with identical desks, where the only sound heard is the endless typing of keyboards. The player’s labour brings no personal fulfilment, representing the reality of modern corporate jobs that feel repetitive and isolating. This phenomenon is known as capitalist alienation, where employees feel disconnected from their work, the products they produce and others. Besides that, the skeleton of a former employee can also be seen in the cutscene, serving as a poignant reminder of how corporate life can drain vitality and reduce people to empty shells.

The opening scene transitions to the escape from this torturous environment, where the player inherits their grandfather’s farm. The player’s relationship with labour then transforms for the better after moving to Pelican town, as their work becomes more fulfilling, with every action they choose having visible effects. For example, planting seeds leads to crops sprouting, chopping wood gives more resources, and caring for farm animals can produce milk or wool. The “new” labour becomes something meaningful and flexible, providing freedom rather than continuous repetition. Therefore, Stardew Valley demonstrates itself to players with a “cure” for capitalist alienation where labour is strongly connected with nature, community, and self.

However, Stardew Valley does not fully abandon capitalism once the player becomes part of the Pelican Town community. Capitalism is an economic system in which individuals and businesses privately own and manage resources with the goal of generating profit, a concept that can be observed in the player’s farm. The farm becomes a business where all the goods the player has collected are sold for profit, giving the player significant control over the market and production. Thus, the farm may resemble a small-scale monopoly, as it often dominates the supply of certain goods in Pelican Town. Unlike real-world monopolies, the game’s idealised version of capitalism transforms labour so that it is never exploitative. The player owns the right to decide what they produce, how they set their own hours and are consistently rewarded for their hard work. Stardew Valley shows a version of capitalism that is both fair and fulfilling, allowing players to experience the benefits of ownership without the capitalist alienation often found in real-world economies.

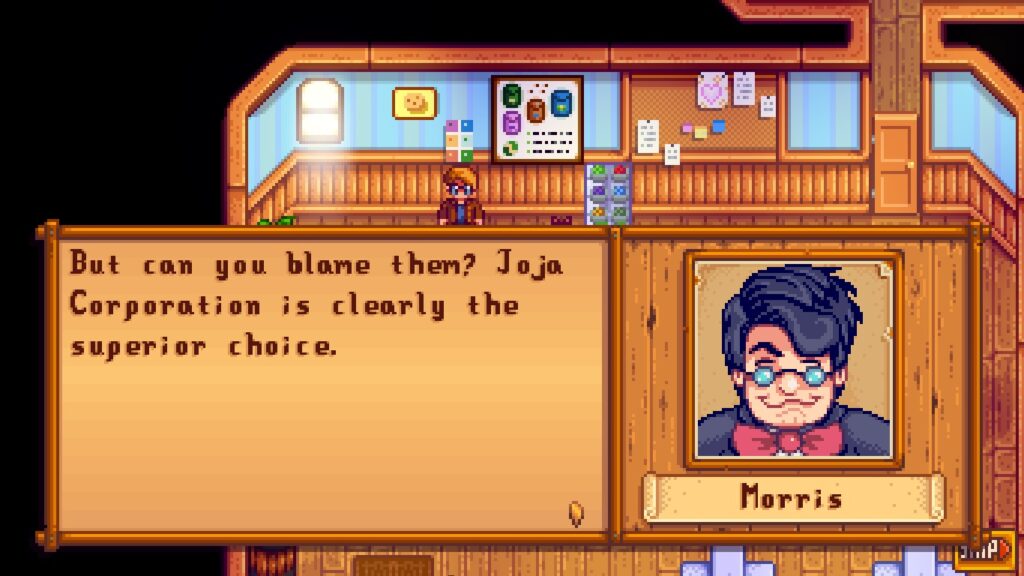

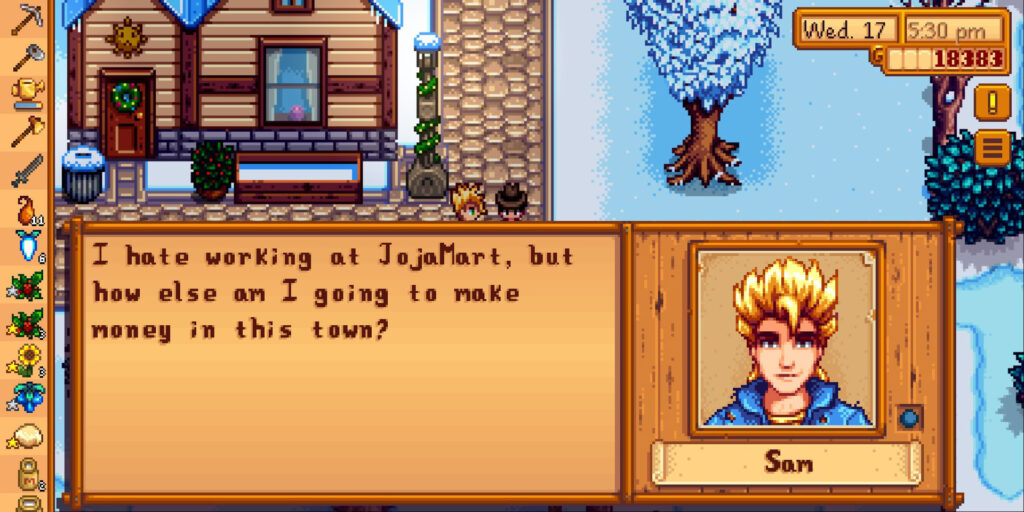

At the same time, the game also reminds players that their past evil employer, Joja Corporation, follows them to Pelican Town, as they reappear in the form of JojaMart. Joja represents the “evil” side of capitalism, where they sell products for cheap prices, dominate the market and exploit workers, all under the management of Morris.

Within economic terms, JojaMart represents real-world monopolistic behaviours of companies, where they aim to control product prices, dominate the market, and limit competition, thereby threatening smaller local businesses, such as Pierre’s General Store. Joja Corporations act similarly to monopolistic companies, aiming to dominate and reduce consumers to passive buyers, with little influence over price changes and a tendency to simply accept what JojaMart offers. The game clearly portrays the villainization of Joja Corporation through visual cues in the opening cutscene, and NPCs (Non-Playable Characters) speak with resignation rather than joy about working with them.

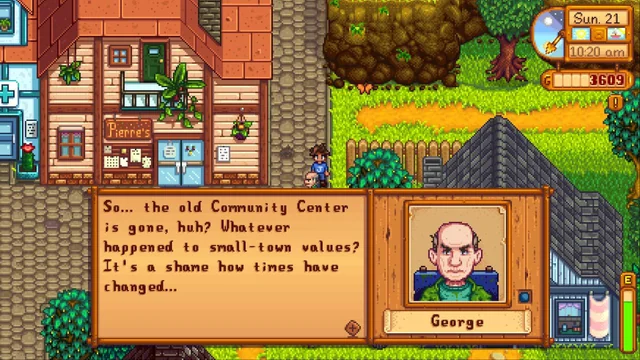

Eventually, the player will reach an event in the storyline where they must make a pivotal decision: whether to side with JojaMart or invest their time, labour, and resources into restoring the Community Centre. By siding with Joja, you begin by purchasing a Joja membership that offers players the convenience of solving problems with money, but it empties Pelican Town of its communal identity. The old, abandoned Community Centre will be changed into a metal-panelled warehouse that clashes with the town’s cozy atmosphere, becoming yet another exploitative workplace for Joja Corporation employees.

However, choosing to restore the community centre requires effort and generosity, but it will be beneficial in revitalising the town and strengthening bonds with neighbours. The game guides players toward what it presents as the “right” path through its storyline and interactions. This is evident in its gameplay, with NPC dialogues and in-game events subtly encouraging players to choose the Community Centre route, framing it as a more ethical and rewarding option.

After restoring the community centre, the player is rewarded with a cutscene where the townsfolk gather happily with balloons for the grand opening, reinforcing the importance of community over corporate dominance, while JojaMart permanently shuts down. Stardew Valley gives the player the option to challenge massive corporations like Joja Corporation through hard work and community cooperation, unlike the reality of capitalism, where small individuals often struggle to challenge them.

Labour and Abundance

As labour becomes an important part of Stardew Valley, it drives progress, wealth and fulfilment. The player begins each day at sunrise and works until late into the night, choosing how they divide their time between farming, mining, foraging or caring for their farm animals. Almost every activity is tied to profit. Contrary to the real world, the game’s resources never fully run out, as forests continue to grow, rivers replenish themselves with fish, and ores within caves renew. It ensures that the player can continue to play without the fear of scarcity, as resources will always be sufficient to meet the player’s needs.

This reflects some aspects of neoliberalism, an economic ideology of capitalism that prioritises minimal regulatory constraints, individual responsibility and privatisation. However, real-world neoliberal systems harshly pressure individuals to view success or failure purely as their own faults, ignoring the societal inequalities. Stardew Valley reflects this individualistic element by placing all responsibility for success on the player, without the need for government aid, unions or competitions. The game reimagines neoliberal pressures as a comforting fantasy where hard work never leads to burnout and debt. Instead, they offer a promise that relentless effort will undoubtedly lead to profit, growth and success. What appears as a cozy escape is actually a structured simulation of capitalist labour, where scarcity disappears, rewards are definite, and the challenges of real-world economics are replaced by the reassuring rhythm of work and success.

When exploitation looks cute

When people think of Stardew Valley, the game Animal Crossing often comes to mind as well, as both share strong ideas about capitalism. In Animal Crossing, the character Tom Nook embodies capitalist structures. He provides the player with a house, but immediately puts them in debt, supporting the real-life aspect where “nothing is free in the world”. Tom Nook acts as a landlord, banker and market all at once. To repay him, players need tools, which they also purchase from him, and he is also the one who buys back the resources they gather. This traps the player in a never-ending cycle of repayment. Most of the wealth flows back to him, even though the player is the one doing all the work, resembling a monopoly. Because of this, many players have joked about him being a villain, as his role perfectly portrays what capitalism is: the labour of many ultimately enriches the few who hold control over resources. The fact that this critique or “joke” is easily understood because the game softens reality by using cute visuals, cheerful music, and friendly townsfolk, demonstrating how aesthetics make exploitation bearable as it is reframed as cozy play.

On the other hand, Stardew Valley is less direct but has the same ideological approach. The game outright portrays Joja Corporation as the villain or “bad” side of capitalism, where the company is exploitative and monopolistic, as evidenced by its lifeless office and low morale among its workers. However, at the same time, they offer the player an “idealised” alternative in the form of inheriting the farm. On the surface, it may appear liberating where they have the freedom to decide and receive visible rewards for their labour. Nevertheless, in reality, the game romanticises this endless cycle of labour, cloaking it with vibrant pixel art, relaxing music and friendly NPCs. They use visuals to depict the huge difference between working at Joja Corporation and working on the farm; however, it is, in fact, similar to the player’s old job, where these tasks in real life may feel monotonous and are reframed as “self-fulfilment.” By aestheticising productivity, the game disguises the fact that it locks the player into a constant cycle of labour for profit.

Animal Crossing highlights the exploitative logic of debt and capitalism, while Stardew Valley persuades players that capitalism can be “fixed”. Joja is portrayed as the villain, while the farm represents a fantasy of “good capitalism” in which profit and community coexist without exploitation. However, this can be misleading as the game erases the exhaustion and inequality of real-world economies. They replace them with an illusion of abundance in resources and security, which makes capitalism seem natural and desirable.

Conclusion

Beneath Stardew Valley’s cozy charm lies a fantasy of capitalism, where work feels satisfying, effort is rewarded, and resources never truly run out. For players, it creates a dream-like world free from alienation, job insecurity and scarcity. Furthermore, the storyline reinforces this idealisation by positioning Joja Corporation as the villain, hinting to players at the “right choice” and offering players a way to resist corporate dominance. Although the game criticised exploitative capitalism, it replaced it with an “idealised” form where the player’s farm functions as a small monopoly, but one that is fair, fulfilling and free of exploitation.

Despite the long hours of in-game labour, from sunrise to late at night, the game uses colourful visuals, comforting music, and friendly townsfolk to turn monotonous tasks into meaningful acts of self-fulfilment. Similar to Animal Crossing, Stardew Valley conceals the harsh reality of capitalism through its aesthetic and unrealistic ideals, such as the small farmer being able to successfully challenge corporate giants. Conclusively, Stardew Valley does not reject capitalism, but softens it, offering an idealised vision of fairness, abundance and community. Its popularity further reinforces the appeal of this dream, but also subverts the idea of a “cozy” game: what seems friendly and relaxing may really be a seductive simulation of work and capitalist logic.