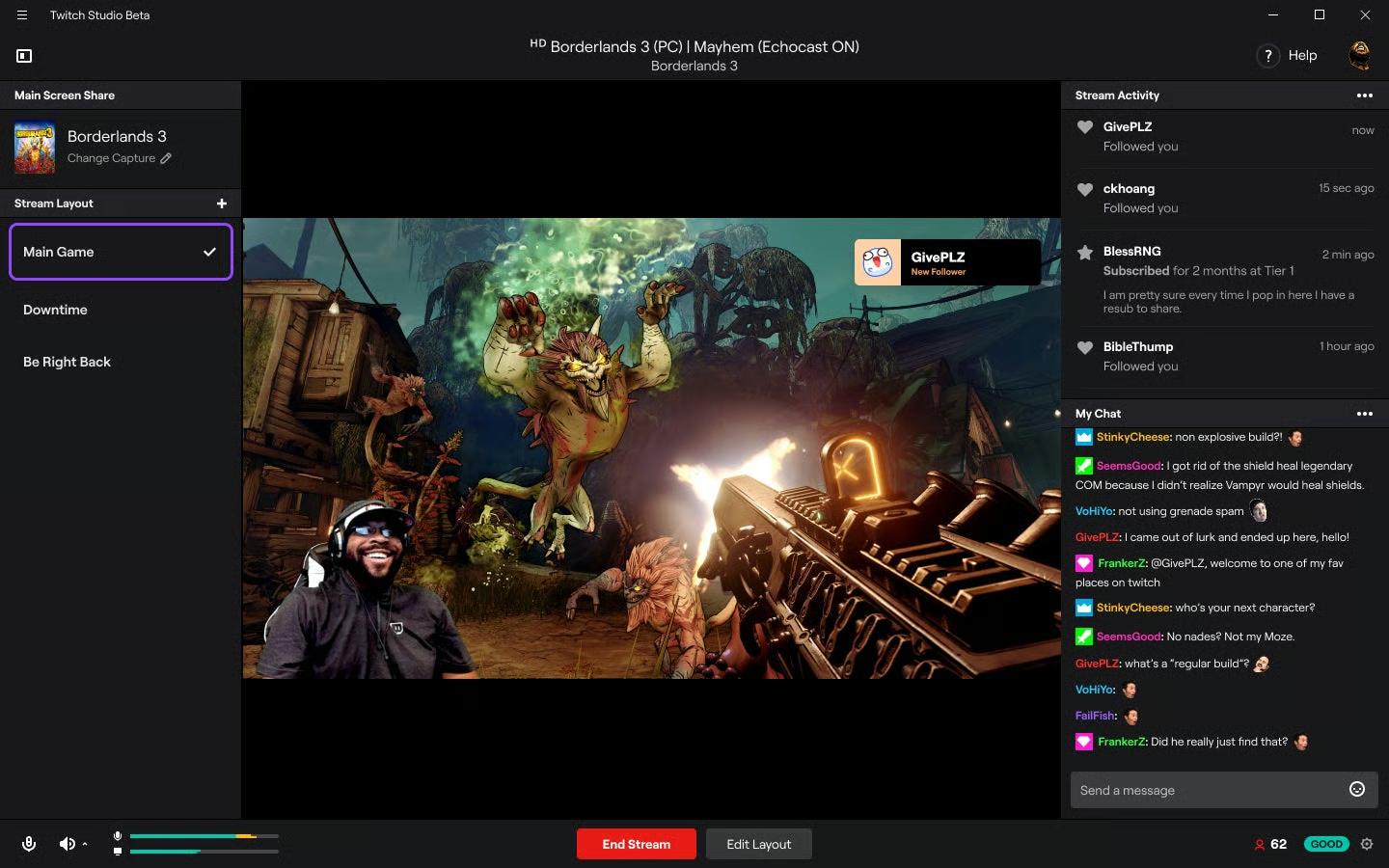

Introduction Every night, millions of young adults watch streamers on platforms like Twitch, YouTube Live, Douyu, and Huya. According to industry reports, Twitch alone sees over 21 billion hours watched annually, with users averaging 95-106 minutes daily. These viewers include gamers, students and remote workers who form deep emotional bonds with streamers they have never met.

Researchers call this a “parasocial relationship,” but this article uses simpler terms: “imaginary friendships.” These are relationships where viewers invest time, money, and feelings into someone who cannot truly know them back.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people turned to streaming for connection. But do these imaginary friendships actually reduce loneliness, or make it worse? While imaginary friendships provide temporary comfort, they work like junk food which satisfies one moment but lacks real nutrition. Over time, they trap viewers in a cycle that deepens loneliness, creates addiction, and prevents real friendships.

Twitch hours watched yearly (2014–2023). Source: Demandsage.

This parasocial relationship could relieve stress and support individual emotion

Research shows imaginary friendships can help during stress. Tan (2023) studied 665 VTuber viewers aged 18-25 during the pandemic. He found that viewers with stronger attachments felt less hopeless: “the more the respondents were parasocially attached to VTubers, the more they were relieved from stress”. The study found positive correlations between parasocial attachment and stress relief.

Why? The steamers will host the live broadcasts regularly every day. The daily broadcast provides predictable comfort through familiar voices and jokes. For those who were isolated during the epidemic lockdown, this provides an emotional sustentation.

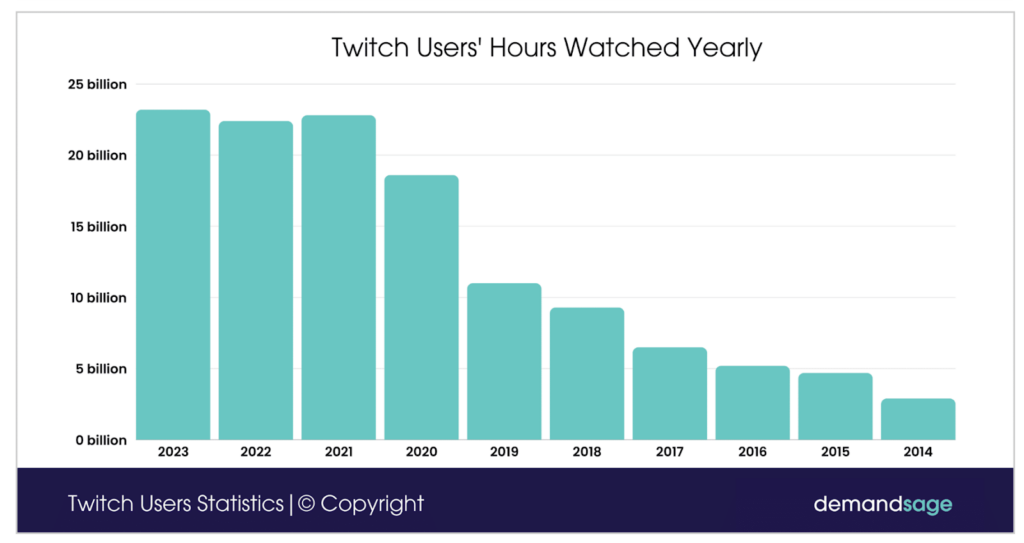

In July 2021, VTuber Kiryu Coco announced her retirement, and her last live broadcast and the number of online viewers at the same time was as high as 491,000. Fans donated USD$306,000 on her last live to thank her. An audience member wrote: “During the lockdown, I couldn’t see anyone. Coco helped me get through the difficult times. Watching her live broadcast every night is like being accompanied by a friend.”

This not only shows sincere emotional support, but also reveals the main problem: 491,000 people feel that they are “accompanied” by someone who can never really understand them.

Kiryu Coco’s graduation became a hot topic online. Source: Reddit.

This parasocial relationship could create collective belonging and show the power of community

The difference between live-streaming and TV is their interactive functions, which create the illusion of a two-way connection. Goh et al. (2021) explained that the platform provides “instant satisfaction, such as instant feedback from the streamer”. Functions such as real-time chat, donation reminder and user name call make the audience feel that they are talking to the streamer, even if the communication is essentially one-way.

TwitchTracker (2025) data shows over 2.1 million people watch Twitch simultaneously on average, with 6.9 million active streaming channels per month. This massive participation creates a collective viewing experienceIn popular live broadcasts, chat messages can reach 10,000 per minute, creating a collective experience.

This phenomenon is not unique to gaming streams. Mathew (2025) observes that social media has created “the illusion of intimacy” across all celebrity culture by replacing traditional one-way communication with interactive features that make fans feel “as if they’re part of an exclusive conversation.” The technical level is different. Instagram Stories and Twitch chat rooms turned out to be the same way: the audience mistakenly thought that they had established a sincere connection with someone they had never met before.

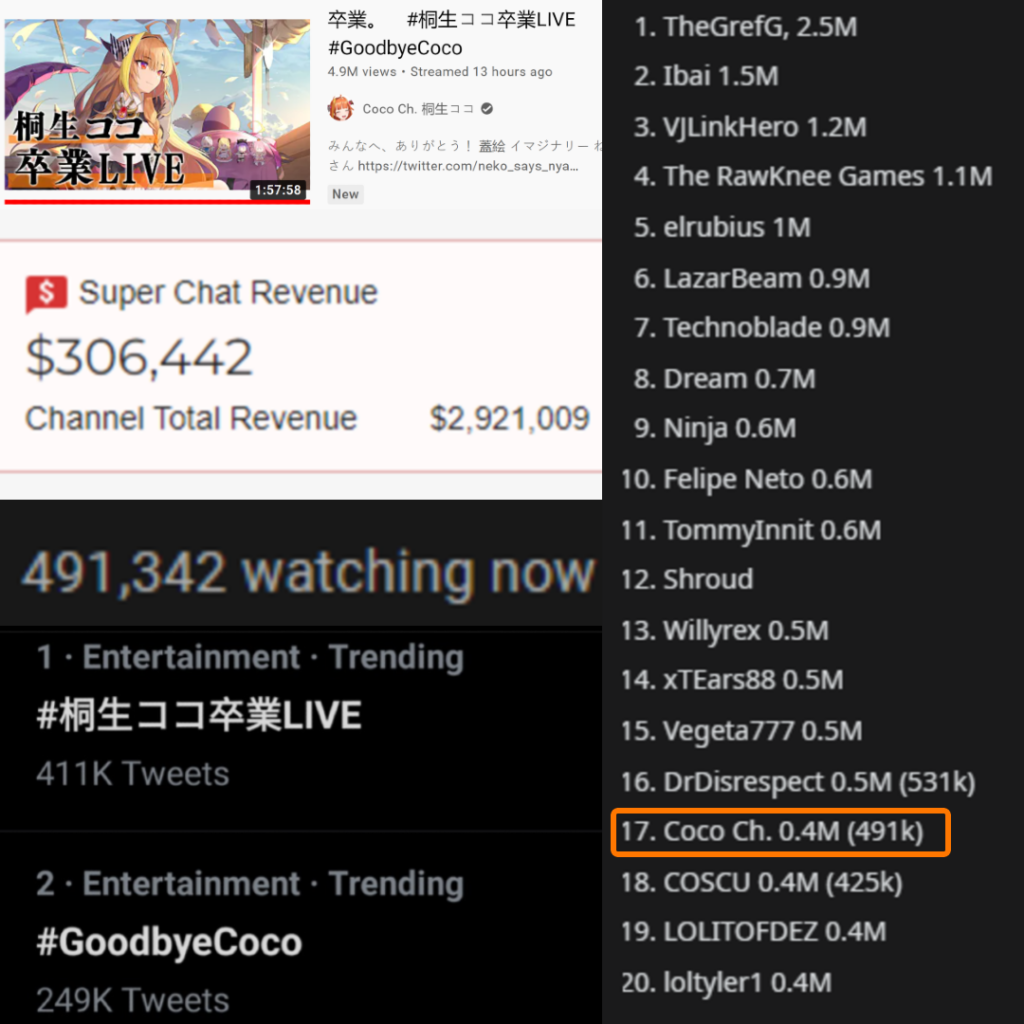

Dr. Alok Kanojia, a psychiatrist streaming as“Dr. K,” demonstrates this potential. His HealthyGamer_GG channel has 1.2 million subscribers, and each meditation live broadcast can attract 15,000 to 25,000 viewers. According to the survey, a mount of viewers feel “no longer so lonely” after watching the live broadcast. However, even Dr. K admits that these live broadcasts cannot replace real psychotherapy or imaginary friendship.

In Dr K’s live stream, many viewers talk to each other. Source: npr.

The addiction part makes things worse

Despite the temporary benefits, a study by Wan and Wu (2020) of 244 Chinese viewers (average age of 21.64) found that imaginary friendships actually exacerbate loneliness. Their findings are shocking:

- Loneliness increased: “Parasocial relationship positively influenced loneliness, b = .301, p < .001”—meaning 30% higher loneliness scores

- Addiction increased: “Parasocial relationship positively influenced addiction, b = .490, p < .001”—meaning 49% higher addiction scores

(Wan & Wu, 2020, p. 5321)

The researchers explain this through “compensatory viewing”: “viewers attempt to seek compensations for unsatisfactory real-world relationships through indulgence in parasocial interactions.” But because these relationships are one-sided, they cannot provide genuine mutual support.

The addiction mechanism works like gambling. Intermittent reinforcement keeps viewers returning. Wan and Wu (2020) found that parasocial relationships strongly predicted addictive viewing behaviors (b = .490, p < .001), with viewers caught in cycles of seeking acknowledgment that rarely comes.

Problems intensify on Chinese platforms through unique cultural practices. Douyu and Huya feature public leaderboards showing top donors. The #1 donor “Number One Big Brother” receives special status and recognition.

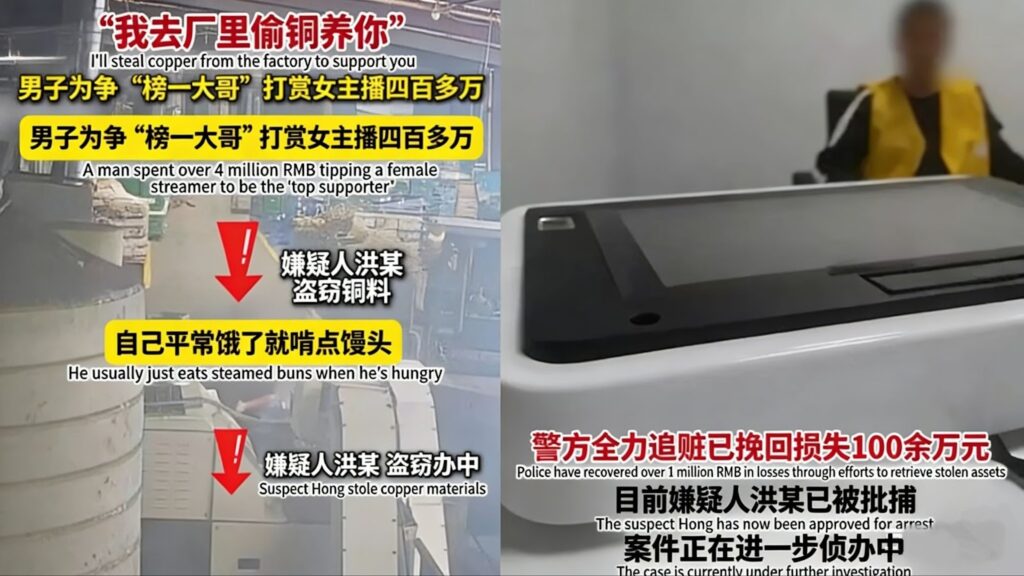

In October 2024, Chinese police arrested a man named Hong for stealing USD$316,000 to donate to a female streamer. Before stealing, he had already spent his family’s entire USD$550,000 life savings over three years USD$15,000 monthly to stay No.1 on the streamer’s leaderboard. He spent 6-8 hours daily watching while neglecting his business and family. When arrested, he said the streamer understood him better than his wife, despite exchanging fewer than 200 messages with her in three years.

A man stole money to give to a female streamer and was later sent to prison. Source: Bastille Post.

The majority of gaming streamers on Chinese platforms are female. Female streamers perform emotional labor beyond gameplay:

- Call donors “gege” (brother) or “dage” (big brother)

- Use sweet voices: “Thank you, brother, for the rocket gift”

- Pretend excitement and gratitude for donations

This creates illusions of romance. Male viewers feel “cared for,” though streamers perform identically for thousands simultaneously.

For example, female streamer Feng Timo received USD$1330,000 in one stream from competing “big brothers.” Each believed they had special connections, but she later admitted not remembering most usernames.

Chinese platforms also feature “PK battles” where viewers donate competitively. In a single PK battle, a top supporter helped their favorite streamer win by tipping gifts worth over USD$380,000.

Fans call streamers “laogong” (husband) or “laopo” (wife). Comments like “laogong jiayou” (Cheer up, my husband!) and “laopo wo ai ni” (I love you, my wife) fill chats constantly. This language reveals romantic fantasies, blurring lines between imagination and reality.

Female viewers on Bilibili Live comprise high percentages. Huya’s 2024 live streaming revenue was about USD$670 million, with roughly USD$0.63 million paying users. This means each paying user contributed around USD$148 per year.

PK Battle in Live-streaming. Source: Youtube.

My opinion on why they make loneliness worse

Replacements, Not Supplements

However, for lonely viewers with few close real-world friendships, imaginary friendships become the meal itself. Research shows lonely viewers are overrepresented among heavy stream watchers. As one participant explained that due to depression or anxiety, it was impossible to build real relationships. For these people, Twitch was a way to have at least some form of social connection.

Wan and Wu (2020) found that parasocial relationships significantly predicted higher loneliness (b = .301, p < .001), indicating that stronger imaginary friendships are associated with increased feelings of isolation.

A Twitch viewer named Alex Flores donated approximately USD$10,000 to streamers over four years, eventually becoming a chat moderator. He later recognized these relationships were “disingenuous and conditional on continuous monetary support,” noting: “If a few weeks had gone by without a donation, it would feel like I would get ignored in chat.“ He originally thought it was a real emotional bond, but it turned out that it was just a trading relationship, which could only be maintained through continuous economic investment.

The Parasocial Trap: How the search for belonging in live streams becomes an expensive illusion of intimacy. Source: Youtube.

There is a fundamental imbalance in these relationships

True friendship requires reciprocity, which means that friendship requires mutual understanding, common experience and balanced emotional input. Imaginary friendship cannot provide this kind of reciprocity due to the limitation of audience size. Imagine that an streamer has 10,000 online viewers at the same time. Even if they read dozens of usernames, reply to comments and confirm donations during the live broadcast, the vast majority of viewers cannot get any personal recognition. Anchors may recognise a few regular donors, but it is mathematically impossible to establish meaningful relationships with thousands of viewers.

The donation model clearly shows the nature of this transaction. When the streamers confirmed the donation, they were really grateful for the money, not the donor himself. For example, in China, top streamers like Sun Ensheng will participate in the “Capital Verification PK” activity to compete to see whose fans can donate the most money in 60 seconds. In these crazy PKs, there are usually young fans, many of whom are students or professional women aged 18-24. They donate their limited pocket money to help the millionaire streamers they support win the game. With just one night’s competition, top streamers can earn more than $141,000 USD, which is far more than the monthly income of their ordinary fans. The platform then intervened and forced the streamers involved to stop the live broadcast on the grounds that they encouraged irrational consumption.

The industry structure reveals this dynamic. Although the specific proportion varies from platform to platform, usually only a small number of highly active viewers contribute most of the streamer’s income through subscriptions and donations. Top contributors will get more attention, thus forming a hierarchy in which money can be exchanged for so-called friendship. But this is not a real connection, but a business transaction disguised as friendship.

One streamer is surrounded by thousands of viewers and cannot reply to every message or remember every user. Source: Doubao.

It could actively prevent real friendships

The time to watch the live broadcast means that there is no time to build real interpersonal relationships. McLaughlin and Wohn (2021) found viewers averaged 6.14 hours per week watching their favorite streamer, with some heavy viewers watching far more. Although this is far from the time investment of full-time work, it still represents a considerable amount of time, which could have been used for face-to-face social interaction and skill development.

This lack of time is not only reflected in time. Social skills will deteriorate due to lack of use. True friendship requires conflict resolution, emotional mutual response and non-verbal communication. And these skills cannot be cultivated in the one-way interaction with the streamer. The audience spends hours in an environment where they can leave at any time without resolving conflicts. The streamers work emotionally but do not get the corresponding support, and the communication is mainly through words. In contrast, these patterns may make it more difficult to have interpersonal relationships that require each other’s exposure and efforts in real life.

Conclusion

Imaginary friendships established with streamers will eventually exacerbate loneliness through three mechanisms: they replace real interpersonal relationships, not supplement real interpersonal relationships; although they feel interactive, they cannot achieve reciprocity from a mathematical point of view; they will take up the time and skills needed to establish real connections.

The numbers are amazing:

- 491,000 watching Kiryu Coco

- USD$550,000 spent by Hong

- USD$10,247 by Flores

Data shows that the live broadcast industry is based on the large-scale and habitual participation of users: today, the market value of the live broadcast industry is close to USD$100 billion, and is growing rapidly to USD$345 billion. Its core driving force is a young and loyal audience: two-thirds of the users are between the ages of 18 and 39, and each viewing time is more than 25 minutes, which is 8 times that of on-demand videos. This is its business model: monetisation of attention and people’s demand for connection, up to hundreds of billions of dollars. Many people are gradually accepting one-sided and carefully crafted friendship, while true intimate relationships are becoming increasingly scarce.

But that doesn’t mean that all live broadcasts are harmful. For those who have a strong and true friendship, live broadcast is a harmless way of entertainment. The danger lies in when imaginary friendship becomes the main interpersonal relationship.

In order to solve this problem, individuals should control his or her viewing time and consumption. The platform should set the viewing time and consumption cap. The streamer should remind the audience that these interactions cannot replace true friendship. Society must solve the root causes – the spread of loneliness, the shrinkage of community space and social anxiety.

Which feels easier? Which attracts you?

Watching live streams alone / Going out with best friends. Source: Baidu & Pixel.