Photo by John Lockwood on Unsplash

In a digital world defined by constant scrolling, every tap, like, and swipe generates valuable data, captured by sophisticated algorithms designed to predict our preferences and keep us engaged. Personalised content makes our online experiences feel effortless, delivering video, music, and shows tailored to suit our tastes. At first, this feels like magic, the perfect playlist, the next must-see series, a short video that hits our sense of humour exactly. Internet growth has exploded, from 2000 to 2022 alone the usage increased by 200 – 600 % in Europe, North America and Australia. As of 2021 there were 4.2 billion social media users with an average screen time of 6.7 hours per day, this has increased to 5.5 billion users in 2024. The convenience of accessing the internet is undeniable it has changed our lives forever, however, behind this convenience there is a cost. The mechanisms that curate what we see may also limit exposure to diverse perspectives, subtly shaping our choices without our awareness. While only two decades ago we imagined digital technologies as tools for boundless connectivity and openness, today that view seems quite naïve. Algorithms not only influence our entertainment choices but also the way we access information and engage with ideas. While they can enhance convenience and reliability, their role in reinforcing patterns of behaviours and preference raises ethical questions about autonomy, diversity of thought, and the larger consequences of filtered digital environments. Understanding this system is vital to navigating a digital landscape responsibly, transparency in choosing algorithm preferences is key to achieving this goal.

Let’s be honest without algorithms, the internet would be absolute chaos, a melting pot of random videos, ads and a barrage of content you aren’t the slightest bit interested in. Algorithms bring order to that noise. They act as invisible curators, filtering billions of posts, articles and clips to deliver most seems most relevant to us. The big tech platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok rely on these systems to make our experiences more personal. Algorithms aren’t the villains of the internet age; in many ways they make our online experiences better. By analysing what we like, share and watch, helping us discover content to enjoy without the effort of having to search for it. When you watch one video about a cute tiny Chihuahua suddenly the internet serves you a barrage of Chihuahua content to keep you scrolling for more, and it’s convenient! For creators and media outlets, this intelligent matchmaking is a game changer. They provide valuable feedback to publishers, revealing what resonates with audiences and what doesn’t. The result is a dynamic ecosystem driven by clicks, shares and engagement. Algorithms help connect their work with the right audiences faster than ever, which is crucial in a digital environment where attention is king and engagement drives success. For many people social media has become their source of information across, news, community and friend groups. Media platforms powered by engagement drive algorithms and have a huge influence on what we see online therefore establishing the importance of media relying on algorithms for performance. In short algorithms are the intelligent achievers behind our digital experiences.

‘In the 21st century, data is the new oil, and machine learning is the engine that powers this data-driven world. It is a critical technology in today’s digital age, and its importance cannot be overstated’ – Selvarajan, G. P. (2024).

Image by My Nguyễn from Pixabay

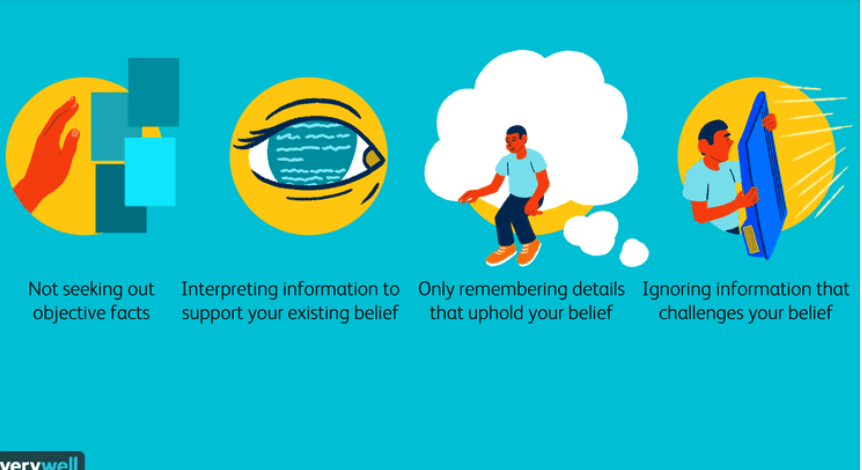

While algorithms make our lives easier there is also a dark side to this convenance. By giving us more of what we already like over and over they learn our preferences and lock onto them like a clingy friend. Over time platforms stop showing us anything unfamiliar. This has created a storm of discussion surrounding the methods used to curate and deliver content raising privacy concerns, concerns surrounding addictions of viewing and ethical delivery of algorithms. Media formats such as Short-video now rule the media landscape enticing users into infinite scrolling with a barrage of content filled with algorithmically selected content. They have gained immense popularity and have changed the way people consume and produce media, this is turn has a huge influence on communication patterns and have influenced cultural expression. When TiktTok launched short video in 2016 the format quickly become a huge success as of 2023 the platform has one billion monthly active users and this has continued to rapidly grow. in 2024 short-form video revenues estimated at a huge $99.4 billion. Another related issue is the ‘eco chamber’ effect. Eco chambers spread and repeat information that matches beliefs and attitudes shared by the group who receive it. People are more readily accessing their news source through social media, these online media outlets have established personalised algorithms, this curated method of delivering content causes the risk of a filter bubble. When our feed is full of content that already agrees with us it supports our beliefs and never challenges our perspectives. This can set a trap into thinking that everyone sees the world as we do, that is until we step outside of this online bubble and realise that actually they absolutely do not.

‘Algorithmic discrimination may include discrimination in terms of race, gender, religion, and so on, which easily leads to disputes and conflicts with a negative impact on human affection, dignity, and trust (Kleinberg et al., 2018)

Digital Media sites are where big data, particularly data representing and collating users behaviour is gathered and sourced continuously. Algorithms collect immense amounts of personal data, often without full awareness or consent. Their goal is not education or exploration, its engagement they are after, to keep us scrolling watching and clicking. The longer we stay on a screen the more profit they generate. Human decisions have been taken away by technology ones, deigned to maintain the monopolistic tech companies need for users data. This creates a troubling paradox. We feel in control because we choose what we want to click, yet invisible systems quietly shape those choices in the background. Algorithms don’t just predict our behaviour, they influence it. When decisions about what we see are made by code optimised for attention, not understanding, the consequences ripple far beyond our screens.

‘Algorithmic recommendations dictate genres of culture by rewarding particular topes with promotion in feeds, based on what immediately attracts most attention’ – Chayka 2024

Credit:Verywell / Daniel Fishel

Algorithms don’t just simply personalise our experiences they quietly fence them in. They occupy a contradictory space in our digital lives, functioning simultaneously as helpful guides and strict gatekeepers. On one hand they provide a level of convenience that is hard not to celebrate on the other they decide what we like leading us deeper in the same familiar loop. We think we are exploring freely, but really, we are going around in circles. It tempting to call this efficiency, every time you open your phone the internet has been pre-sorted especially for you. But this convenience can disguise control, the internet once felt like a place for discovery, a wild unpredictable mix of information and creativity. Algorithms tamed that chaos, but they have also flattered it. What now shows up in our feeds feels much less like a surprise and more like déjà vu.

‘Social media platforms have become tainted over time with algorithms that can hijack conversations, influence others decisions and manipulate distribution of content’ – Polaec & Ghergut-Babii

To me that’s a huge problem. When algorithms predict our next move, they are not doing it to inspire or challenge us, they are doing it to hold our attention. The more we scroll the more they learn. Our feeds now feel like a comfy pair of slippers, but this comfort can be confining. If you interact with a fitness video, you’ll see more fitness videos. If you like political post from one side, you’ll almost never see perspectives from the other. This is why users should have real control over their feeds. Users deserve to know and decide how personalisation works, not just simply accept it. Imagine being able to adjust your feed the way you curate your playlist, opening the prospect of new perspectives, getting rid of the repetition or even choosing to change recommendations all together. The power to shape what we see should sit with us not the corporate algorithms. Transparency is key. Most platforms treat their recommendations systems as secret formulas, never to be released or discovered, but understanding them shouldn’t be withheld. When users are privy to the reasons why certain content is being presented to them and have the tools to adjust what’s prioritised they can break free from the confines of algorithms. This empowers the user to embrace choice and free thought. If platforms embraced openness, everyone would benefit. Users would trust the platforms more, creators would reach broader audiences, and society would gain from richer more balanced views. By designing algorithms that invite curiosity and exploration rather than repetition, companies create healthier digital spaces.

The truth is simple, algorithms serve as business models, not for human curiosity or learning. They optimised for attention, not diversity. Giving users the power to shape their feeds is how the balance of power should be placed back with users. Personalisation should be something we direct not something that is done for us. Technology works best when it expands our horizons, not when it fences them in. The goal isn’t to rid the internet of algorithms but to demand transparency to respect choice and diversity. When users can decide on their own journey algorithms can truly become tolls for discovery instead of controlling and narrowing our digital choice. Users should be in control, period. The moment algorithms choose what we see, they choose what er don’t see and that’s a cost far too high that cannot be justified. the fix is simple, hand back the power to the user. We should decide what we watch, read and believe, not a hidden algorithm. The internet should help us explore the world; it should broaden our horizons not shrink it to fit our habits. Ultimate control belongs to us.

Clip by Kristian Ozer Kettner

Algorithms have become powerful gatekeepers in our digital lives. They offer the undeniable benefits of personalisation, convenience and connection but they also trap us into a loop of sameness. Their influence extends beyond entertainment into the way we from opinions and understand society. That’s why accountability is crucial. Media organisations have always worked to understand their audiences so their messages reach a receptive audience, the use of algorithms has super charged this ability. Media platforms must be transparent about how their recommendations systems work given the power of choice back to the user. Policy makers must understand the working of algorithms to provide sound governance and oversight of platforms technologies. To avoid eco chambers and filter bubbles platforms must accommodate preference centres that allow individuals to customise their feeds, broaden perspectives and to understand how content is filtered. This transparency is key to maintaining trust and transparency. Ultimately, algorithms are tools, neither good nor bad on their own, they reflect the intentions behind them. When designed responsibly and guided by informed users, digital media can remain exciting, entertaining and informative, but only if choice remains in the hands of the viewer. The future of online media must follow one principle; convenience should never be in control, the algorithm should never dominate, it is the user that must have ultimate power.

References and links:

Chayka, K. (2024). Filterworld: How algorithms flattened culture. Doubleday. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=5qojEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=facebook+algorithms&ots=TMf0ia9uD5&sig=v7rHkSnpg-Y6eS-M_3DrSGSD6ik&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=facebook%20algorithms&f=false

Chen, Y., & Li, T. (n.d.). A study on algorithm controversy in the new media era. [Journal Name]. https://doi.org/10.70267/dn1y1425

Chen, L. (2023). Exploring the impact of short videos on society and culture: An analysis of social dynamics and cultural expression. Pioneer International Journal, 6(3). https://rclss.com/pij/article/view/420

Cherry, K. (2021, January 24). Confirmation bias: Seeing what we want to believe. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-confirmation-bias-2795024

de Groot, T., de Haan, M., & van Dijken, M. (2023). Learning in and about a filtered universe: Young people’s awareness and control of algorithms in social media. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(7), 701–713 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/17439884.2023.2253730?needAccess=true

Ebrahim, T. Y. (2020–2021). Algorithms in business, merchant-consumer interactions, & regulation. West Virginia Law Review, 123, 873 https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/wvb123&div=29&id=&page=

Fisher, E., & Mehozay, Y. (2019). How algorithms see their audience: Media epistemes and the changing conception of the individual. Media, Culture & Society, 41(8), 1176–1191. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/0163443719831598

Lasser, J., & Poechhacker, N. (2025). Designing social media content recommendation algorithms for societal good. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1548(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15359

Li, W. (2025). The impact of short-video platform algorithms on social aesthetics and public cognition.Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies, 1(5). https://doi.org/10.61173/fa0je598

Kleinberg, J., Ludwig, J., Mullainathan, S., & Sunstein, C. R. (2018). Discrimination in the age of algorithms. Journal of Legal Analysis, 10(11), 113–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laz001

Meng, S.-Q., Cheng, J.-L., Li, Y.-Y., Yang, X.-Q., Zheng, J.-W., Chang, X.-W., Shi, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, L., Sun, Y., Bao, Y.-P., & Shi, J. (2022). Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, Article 102128.

Nesi, J., Telzer, E. H., & Prinstein, M. J. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of adolescent digital media use and mental health. Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=SDCHEAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Petrescu, M., Krishen, A.S. The dilemma of social media algorithms and analytics. J Market Anal 8, 187–188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-020-00094-4

Poleac, G., & Gherguț-Babii, A.-N. (2024). How social media algorithms influence the way users decide: Perspectives of social media users and practitioners. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 57, 69–81. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/techssj57&div=7&id=&page

Ranalli, C., & Malcom, F. (2025). What’s so bad about echo chambers? Inquiry, 68(10), 3984–4026. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2023.2174590

Selvarajan, G. P. (2024). The role of machine learning algorithms in business intelligence: Transforming data into strategic insights. International Journal of Advanced Research and Interdisciplinary Scientific Endeavours, 1(7), 391–391. https://doi.org/10.61359/11.2206-2440

Shin, D., & Park, Y. J. (2019). Role of fairness, accountability, and transparency in algorithmic affordance. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.019

Swart, J. (2021). Experiencing Algorithms: How Young People Understand, Feel About, and Engage With Algorithmic News Selection on Social Media. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008828

Violot, C., Elmas, T., Bilogrevic, I., & Humbert, M. (n.d.). Shorts vs. regular videos on YouTube: A comparative analysis of user engagement and content creation trends [Manuscript]. University of Lausanne; Indiana University Bloomington; https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3614419.3644023

Wallace, J. (2017). Modelling Contemporary Gatekeeping: The rise of individuals, algorithms and platforms in digital news dissemination. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1343648

https://www.feedhive.com/blog/harnessing-the-power-of-short-form-video-strategies-for-2025