In an era where a single tweet can spark a revolution, social media has become the loudspeaker of a generation. From the streets of America to the steps of the Australian Parliament, digital hashtags have mobilised millions and reshaped public debate.1 Hashtags are words or phrases preceded by a hash symbol used on social media to categorise content, join conversations, and connect with others.2 They’ve become a key part of online communication, helping users organise posts, follow trends and promote social movements like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter.

#BlackLivesMatter was founded in 2013 by three Black community organisers after the fatal shooting of unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin.3 The movement grew into a global campaign against racial injustice and police violence, gaining momentum after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, sparking nationwide protests of 15–26 million people—the largest in U.S. history.4 #MeToo went viral in 2017, transforming from a local grassroots effort into a global campaign that united millions of sexual violence survivors.5 Today, it continues to support diverse survivor communities while advocating for accountability and systemic change to end sexual violence altogether.6

These examples show how digital spaces have become a central stage for activism, where hashtags evolve from online expressions of solidarity into global movements demanding justice. Yet beneath the viral momentum lies a deeper question: can online activism truly change the world, or does it stop at awareness? Social media has certainly transformed how movements gain visibility and mobilise support, but its ability to create lasting, structural change depends on whether digital activism is paired with offline organising, political engagement and institutional reform.

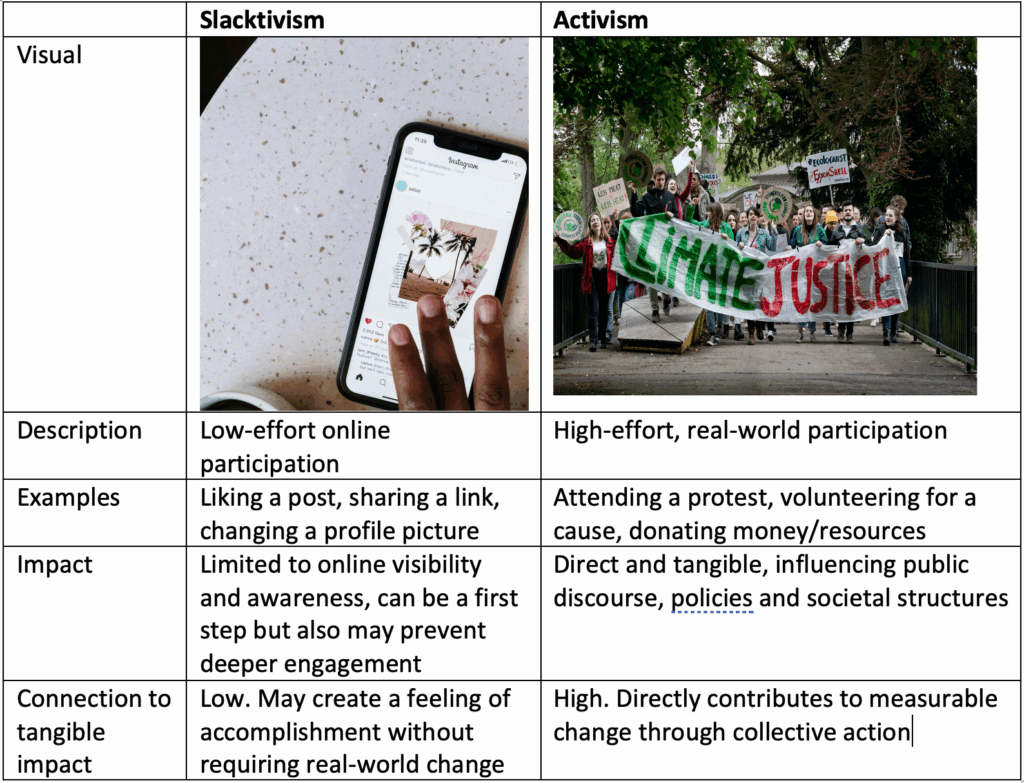

The Limits of Slacktivism

Critics argue that social media activism fosters slacktivism, where “minimal effort actions [are] taken in support of a cause”,7 prioritising visibility over action. In this view, the ease of liking, sharing or retweeting allows users to feel politically active without engaging in meaningful, tangible efforts for change. As Watters explains, “Digital activism has transformed the way events, protests and movements are organised, helping to mobilise supporters and raise awareness of a diverse range of causes. But critics argue that people can feel like they’re making a difference, when in reality they’ve done very little.”8

Before exploring these criticisms, it is important to understand what scholars mean by social media activism. Chon and Park conceptualised it as “a fundamentally communicative process that involves individuals’ communicative actions to collectively solve problems.”9 This definition highlights the interactive and collaborative nature of digital activism, emphasising communication and collective problem-solving as its core functions.

However, despite this communicative potential, critics maintain that social media activism often struggles to produce tangible outcomes. Arnot et al.10 found that while Australian youth view social media as an essential platform for climate activism, their online engagement rarely translates into offline political participation or policy influence. The researchers highlight that visibility and awareness are necessary but insufficient, as the structures of political decision-making remain largely insulated from social media influence.

This is is also echoed in critiques of online climate activism, whereby despite awareness campaigns like #FridaysForFuture, many governments have failed to implement significant policy reforms.11 The performative element of online engagement—changing a profile picture, sharing a post or using a trending tag—often substitutes for deeper involvement.

So while digital tools have expanded access to activism and awareness, critics argue that these platforms risk creating an illusion of participation without meaningful progress.

The Power of Digital Mobilisation

Supporters of social media activism, however, highlight its transformative potential to democratise voices and mobilise people at scale. According to Freelon et al.12, platforms including Twitter and Facebook have redefined public discourse by enabling grassroots mobilisation and connecting activists across borders. They note that “although the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was created in July 2013, it was rarely used through the summer of 2014 and did not come to signify a movement until the months after the Ferguson protests.”13 Their analysis revealed that “social media posts by activists were essential in spreading Michael Brown’s story nationally” and that “protesters and their supporters were generally able to circulate their own narratives on Twitter without relying on mainstream news outlets.”14 These findings demonstrate that social media enabled marginalised communities to control the framing of their own stories, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and influencing mainstream discourse on racial justice.

Bowman et al.15 further argue that #BlackLivesMatter achieved more than symbolic awareness, as it translated online mobilisation into policy conversations at the municipal and federal levels in the U.S., contributing to discussions about police accountability, community oversight and racial bias training.

Another example is the work of Mendes et al.16, explaining that #MeToo reshaped global conversations on sexual harassment, prompting legal reforms, corporate accountability measures and shifts in workplace policy. They argue that the movement’s success lies in its ability to blend viral online participation with offline advocacy by journalists, lawyers and activists. Mendes et al. note that “these campaigns are providing important spaces for a wider range of women and girls…to participate in public debates on sexual harassment, sexism and rape culture”17, highlighting how digital platforms enable both visibility and collective action in addressing systemic abuse.

Newer generations are particularly adept at this hybrid activism. Jude and Padmakumari18 found that Generation Z perceives social media activism as a gateway to broader engagement, using platforms both to educate peers and coordinate real-world initiatives. This challenges the notion that online activism is purely superficial; rather, it represents an evolving form of civic participation adapted to the digital age.

Therefore, proponents contend that while social media activism may begin online, it frequently serves as the spark that ignites real-world movements.

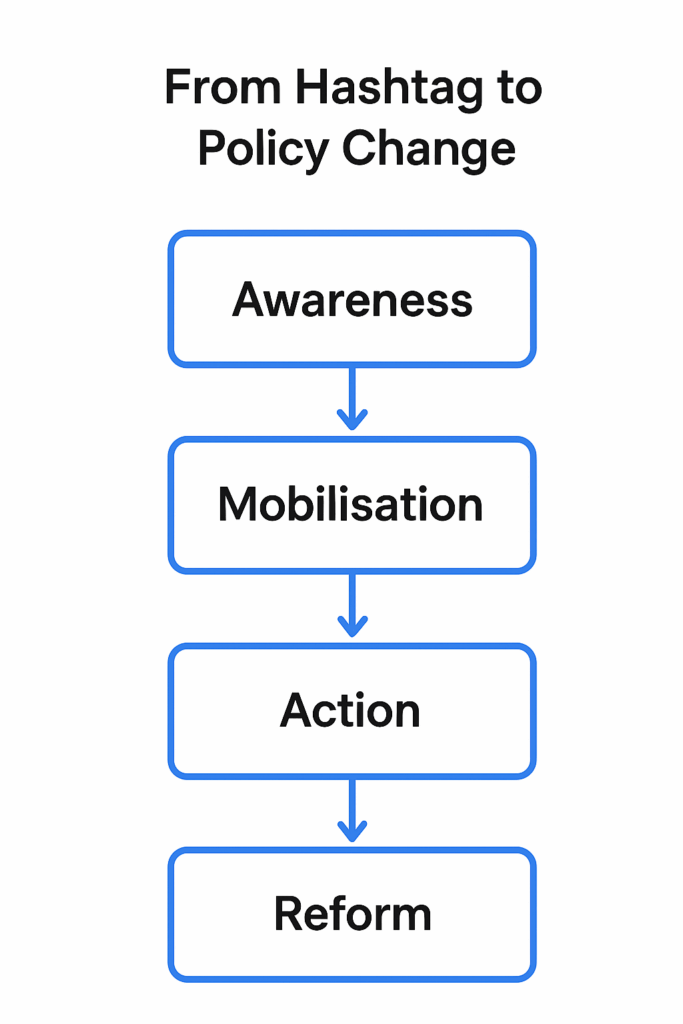

Awareness as a Catalyst, Action as the Outcome

Both perspectives capture partial truths. Social media activism is powerful in raising awareness, but its limitations are clear when it remains confined to digital spaces. The key to effectiveness lies in the connection between online visibility and offline advocacy. Awareness is the necessary spark, but action sustains the flame.

- Awareness as the First Step

Digital platforms amplify marginalised voices, allowing stories and issues to reach audiences at unprecedented speed and scale.19 Bestvater et al.20 report that many adults believe social media helps people engage with political and social issues, with 46% of users taking actions like joining groups, encouraging others or using issue-related hashtags. Movements like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter illustrate how personal testimonies, once silenced, found resonance across millions of users, shifting cultural norms and reframing public discussions around gender and race. Greijdanus et al. note that social media facilitates online activism “by documenting and collating individual experiences, in community building and norm formation, and in the development of shared social realities”21, enabling marginalised groups to participate in collective action.

- Mobilisation and Collective Action

Online spaces also facilitate coordination of protests and fundraising efforts. Arnot et al. state that social media provides “catalystic opportunities to harness young people’s engagement”22 however, sustaining movements requires long-term structure. The success of #FridaysForFuture, a youth-led movement that began in 2018 when Greta Thunberg and young activists staged daily climate protests in Sweden23, demonstrates how online coordination can lead to consistent, large-scale physical demonstrations involving millions of youth worldwide.

- The Limits of Digital-Only Engagement

However, virality is not synonymous with success, and many movements fade as public attention shifts. Arnot et al.24 observed that young Australians felt empowered by digital climate activism but frustrated by its lack of policy traction. This disconnection highlights a broader problem: while awareness campaigns thrive on immediacy, policymaking operates through slow, institutional processes. Without translation into political lobbying, activism risks becoming an echo chamber—where people often connect with like-minded users online, seeing mostly content they agree with, reinforcing their beliefs and obscuring alternative perspectives.25

- When Online Activism Succeeds

Successful cases show that social media can be the starting point for real change. Bowman et al.26 document how the #BlackLivesMatter movement prompted police departments across the United States to adopt reforms, including body cameras and revised use-of-force policies. Similarly, Mendes et al.27 detail legislative changes inspired by #MeToo, such as stronger anti-harassment laws in several countries. In these examples, digital engagement merged with offline advocacy—journalists exposed misconduct, lawyers pursued justice and communities organised public demonstrations. Greijdanus et al. emphasise that “online activism participation can stimulate individuals to also protest offline… Small online actions can ease people into more costly offline action.”28

- The Need for Sustained, Hybrid Activism

For social media activism to achieve lasting impact, it must evolve beyond awareness and integrate with institutional processes. Watters29 emphasises that the future of digital activism lies in hybrid strategies combining online momentum with real-world structures like non-profits, unions and political coalitions. In the context of climate change, this means moving from hashtags like #ClimateStrike to lobbying for renewable energy legislation or supporting candidates with green policies. Online activism strengthens such hybrid approaches because “both intrapersonal and interpersonal consistency between online and offline activism paint a general picture of collective action as positively related across the two domains.”30

Social media activism is neither wholly effective nor entirely ineffective. Its true potential lies in its ability to spark awareness, amplify marginalised voices, and mobilise communities—but lasting change demands more than a viral moment. Movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo demonstrate that when digital visibility connects with real-world organising and legal advocacy, transformation becomes possible.

In the end, hashtags ignite conversations, but policies sustain them. Activists, policymakers, and citizens alike must learn to harness the speed and reach of digital platforms without neglecting the enduring power of collective, offline action. As Watters31 reminds us, the future of activism is not digital or physical—it is both.

References

Advocacy. (2024, November 28). The intersection of slacktivism and impactful activism. Change.org. https://www.change.org/l/us/what-is-slacktivism

Arnot, G., Pitt, H., McCarthy, S., Cordedda, C., Marko, S., & Thomas, S. L. (2024). Australian youth perspectives on the role of social media in climate action. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 48(1), 100111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anzjph.2023.100111

Bestvater, S., Gelles-Watnick, R., Odabaş, M., Anderson, M., & Smith, A. (2023, June 29). Americans’ views of and experiences with activism on social media. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/06/29/americans-views-of-and-experiences-with-activism-on-social-media/

Bowman, J., Mezey, N., & Singh, L. (2021). #BlackLivesMatter: From Protest to Policy . Race, Gender, and Social Justice, 28(1), 103–167. https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/facpub/article/3439/&path_info=_BlackLivesMatter__From_Protest_to_Policy.pdf

Burke, T. (2025). Get to Know Us | History & Inception. Me Too Movement. https://metoomvmt.org/get-to-know-us/history-inception/

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2022, February 27). Black Lives Matter – Subsequent protests: George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-Lives-Matter/Subsequent-protests-George-Floyd-Ahmaud-Arbery-and-Breonna-Taylor

Freelon, D., McIlwain, C. D., & Clark, M. D. (2016). Beyond the Hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the Online Struggle for Offline Justice. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2747066

Fridays For Future. (2024). Fridays For Future. Fridaysforfuture.org. https://fridaysforfuture.org/

Greijdanus, H., de Matos Fernandes, C. A., Turner-Zwinkels, F., Honari, A., Roos, C. A., Rosenbusch, H., & Postmes, T. (2020). The psychology of online activism and social movements: relations between online and offline collective action. Current Opinion in Psychology, 35(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.003

Jude, A. V., & Padmakumari P. (2025). Social media activism: Delving into Generation Z’s experiences. Communication Research and Practice, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2025.2554375

Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2018). #MeToo and the Promise and Pitfalls of Challenging Rape Culture through Digital Feminist Activism. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506818765318

O’Connell, B. (2023, December 20). The #Relevance of Hashtags in the Digital Age. Canterbury Today. https://canterburytoday.co.nz/the-relevance-of-hashtags-in-the-digital-age/

Sudirman, Rosmilawati, S., Toun, N. R., & Riyanti, N. (2024). Hashtags, Resistance, and Reform: The Global Rise of Digital Activism. Sinergi International Journal of Communication Sciences, 2(4), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.61194/ijcs.v2i4.681

University of Sussex. (2022, June). Is digital activism effective? | University of Sussex. University of Sussex – Study Online. https://study-online.sussex.ac.uk/news-and-events/social-media-and-campaigning-is-digital-activism-effective/

Watters, R. (n.d.). Digital Activism: The Good, the Bad, the Future. Humanitarian Academy for Development. https://had-int.org/digital-activism-the-good-the-bad-the-future/

- Sudirman et al., 2024 ↩︎

- O’Connell, 2023 ↩︎

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022 ↩︎

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022 ↩︎

- Burke, 2025 ↩︎

- Burke, 2025 ↩︎

- Advocacy, 2024, para. 3 ↩︎

- n.d., para. 1 ↩︎

- 2019, as cited in Jude & Padmakumari, 2025, p. 2 ↩︎

- 2024 ↩︎

- Arnot et al., 2024 ↩︎

- 2016 ↩︎

- Freelon et al., 2016, p. 5 ↩︎

- Freelon et al., 2016, p. 6–7 ↩︎

- 2021 ↩︎

- 2018 ↩︎

- 2018, p. 244 ↩︎

- 2025 ↩︎

- University of Sussex, 2022 ↩︎

- 2023 ↩︎

- 2020, p. 51 ↩︎

- 2024, p. 2 ↩︎

- Fridays For Future, 2024 ↩︎

- 2024 ↩︎

- Watters, n.d. ↩︎

- 2021 ↩︎

- 2018 ↩︎

- 2020, p. 50 ↩︎

- n.d. ↩︎

- Greijdanus et al., 2020, p. 51 ↩︎

- n.d. ↩︎