You may have seen all those new apps popping up every few months with promises of helping women “take control” of their bodies. Examples such as Flo, Clue, and Natural Cycles all claim to offer freedom through data tracking. The usual marketing tactic is pastel icons, wellness slogans, and an aesthetic tracking dashboard with the same call for action: download, log, and learn today! For women who have grown up surrounded by diet apps, fitness trackers, and digital advice disguised as care, this pitch feels almost comforting.

But beneath all those friendly “you’ve got this” notifications, a deeper problem lies underneath. The same system that once dismissed women’s health in hospitals is now disguising itself in code. Femtech, short for female technology, promises liberation, but instead often delivers the digital version of an old trap where women’s health is still being simplified, commodified, and even sometimes even controlled.

The Empowerment Illusion

Mainstream media, tech powers, and investors have praised Femtech as a revolutionary way for women to understand their own bodies. Advertisements often describe these apps as digital companions, urging users to “get to know your body” or “own your health.” Articles promote and praise the innovation as a feminist milestone, a moment where technology has finally acknowledged that women’s bodies deserve attention.

This perspective is seductive, and on the surface, it makes sense as many women feel that a period-tracking app is a small victory in a healthcare system that is often ignored. But empowerment filtered through algorithms quickly begins to look more like homework. As sociologists Hendl and Jansky (2021) explain, Femtech’s version of empowerment often looks more like self-monitoring, rather than liberation. The more data you log, the more “in control” you’re told you are. Miss a day? You’ll get a gentle ping: Don’t forget to log in today! What looks like control is often unpaid labour disguised as self-care.

The illusion of control extends into the market itself. Legal scholar Zokaitytye (2025) argues that Femtech didn’t just adapt to capitalism, rather it was built on it.Data about women’s reproductive cycles, sleep, and sexual health are not just medical records and are instead used as a tradable value. Companies are re-packaging user “insights” into premium features and selling them back through their subscription models, creating a feminist asset paradox.

Biotech journalist Johnson (2024) acknowledges that Femtech has huge potential, but warns that the industry’s business model still operates inside a tech culture that sells convenience over equality. These quick-fixes risk replacing real healthcare with aesthetic, digital band-aids. Jelena S. points out that this pattern isn’t new in her hot take on American Eagle’s Great Jeans or Great Genes campaign, noting that marketing is not neutral; it picks a side and calls it a style. Femtech borrows that playbook to make confidence a look, empowerment a brand, and control as a subscription.

Even the tone differs by gender. Men’s fitness tracking, like Fitbit or Garmin, celebrate “performance” and “progress” through hard metrics. Femtech apps push responsibility and for women to “stay balanced.” When men’s trackers miss a workout, it’s a lost streak; when women miss a log, it’s a warning. There are different promises and different burdens as one group measures success whereas the other manages risk.

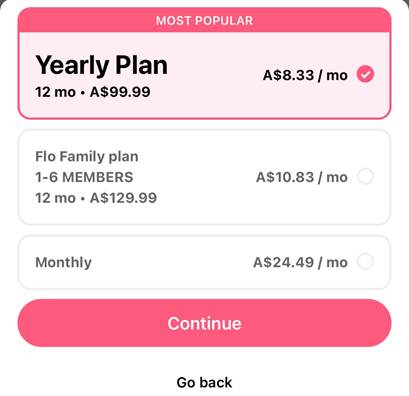

And even “accessibility” comes at a price. When Flo first introduced its expert approved advice for $24.49 a month, it was monetising both health and uncertainty. Premium tiers lock features behind paywalls, turning health insights into a luxury. Zokaitytye (2025) calls this a feminist asset paradox, where empowerment turns into something that women must now pay to reclaim. As researchers Ganle and Dery (2015) highlight, women in low income or non-Western regions already face significant barriers to healthcare, and these apps do little to help or change that.

Into the Femtech Paradox

Behind the pastel marketing and branding lies something that women are familiar with:a healthcare system that still expects women to wait. One of Femtech’s biggest selling points is the promise to bridge gaps in medical research as women’s health has historically always been underfunded and understudied. Endometriosis, for instance, takes an average of eight to ten years to diagnose (Borghese et., 2015), and PCOS affects up to one in five women globally but remains widely underdiagnosed (Gu et al., 2022).

Apps like Flo and Clue claim to “spot irregularities early,” yet as Dixon et al. (2023) found, these tools track data but it can’t diagnose. Femtech hasn’t solved diagnostic delay, it has simply digitised the waiting room.It is proof that even with the latest tech, women are still asked to wait for answers again and again. Akiyama et al. (2018) further warns that generic treatments often delay diagnosis and increase costs over time, serving as a warning that perfectly fits the approach of Femtech’s one-size-fits-all advice. When users log symptoms like pain or heavy bleeding, they’re met with automated empathy: “try rest,” “reduce stress,” or “talk to your health professional.” It’s the same patronising suggestion that never answers why these issues exist in the first place. Hofmann (2024) notes that Femtech empowerment languages are just a form of digital gaslighting, framed to make you feel that if the app doesn’t help, then maybe you didn’t use it right.

The gap gets further when you look at privacy issues as the data that these apps collect aren’t always private as it seems. A 2022 study and a 2023 analysis of Femtech privacy warns that many reproductive-health websites still share sensitive information with third-party advertisers. What was sold as “owning your data” often meant someone else owns it first. In the U.S., the stakes are concrete as in the first year after Dobbs, at least 210 people faced criminal charges related to pregnancies, and the highest documented in a single year. Forbes’ Dubiniecki (2024) connects the dots by noting that period-apps and wellness data, not protected like medical records, can become ready-made portfolios for law enforcements in a post-Roe environment, even in states where abortions remain legal.

Flo’s response to earlier scrutiny about privacy has included public facing charges, however its own website material still acknowledges that information is shared to analytical partners. This raises questions about what is collected, how long it’s kept for, and what can be used to produce evidence in court.

Tech journalist Dhar (2023) reminds us that most users have no idea how exposed their data really is. Concerningly, in conservative U.S. states where abortion is banned, lawmakers have even proposed data from period-tracking apps to monitor missed cycles. Empowerment can quickly become surveillance, and the app that promised privacy and care can become a quick informant.

This goes further than privacy, it’s now also about trust. Hendl and Jansky (2021) describe “algorithmic intimacy” as when an app learns your patterns better than a clinician as you continue to confide in it. The danger with that is that Femtech normalises intimacy as a form of “care.” However, code cannot empathise, and women’s pain should not be reduced to metrics on a dashboard.

The Burden of Responsibility

Femtech also reflects a deeper structural issue in women’s healthcare where women receive the same old “solutions.” One of Femtech’s biggest selling points is the promise to bridge gaps in medical research. Historically, women’s health has always been underfunded, understudied and undervalued. Conditions such as endometriosis still take around an average of eight to ten years to diagnose (Borghese et., 2015), and PCOS also affects up to one in five women globally but remains widely underdiagnosed (Gu et al., 2022). Apps like Flo and Clue claim to help identify patterns and empower women to “spot irregularities early,” but researchers such as Dixon et al. (2023) found, these tools rarely lead to better outcomes as they can track data but can’t diagnose. It is proof that even with the latest tech, women are still asked to wait for answers again and again.

Femtech didn’t invent the quick-fix mentality towards women’s health, it just digitised it. Hormonal birth control has been prescribed as a “solution” for almost everything for as long as they’ve been available. Whether it be for cramps, acne, irregular periods, heavy bleeding, and even depression. The issue? It rarely addresses the cause.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. Femtech’s “feminist” glow hides a massive data business behind it. A 2023 study by Alfawzan and Christen found that most period tracking apps still quietly share or monetise the data of its users, even when they advertise a “privacy first” promise. With current events in America, where abortion is criminalised in parts of the country, that’s not just unethical, it is dangerous. Legal experts warn that menstrual-cycle data and search histories have already appeared as evidence in court cases.

These patterns also keep older gendered expectations alive, especially the idea that women must handle reproduction and contraception alone. Male contraceptive trials are often halted over mild side effects, whereas women are expected to accept the harsh effects as part of “being responsible.” Apps coach users to “plan responsibility” and “manage fertility.” Yet none ask why the burden of reproductive control is always on the women to handle. Hoffman (2024) highlights that these apps turn unpaid self-surveillance into a new normal of empowerment. Real progress would look like shared responsibilities and a better health care system, not another pastel reminder telling women to stay balanced and keep paying up for another month.

Beyond the App

Femtech did begin with good intentions as it aimed to close gender gaps in medical research and give women insight into their own bodies. However, when profit is prioritised, the industry turns empowerment into another digital product.

Facca et al. (2025) critique Femtech as a technological mirror that reflects the same biases and blind spots that shaped medicine in the first place. The apps promised liberation but ended up just repeating old mistakes in a different form.

The next generation of Femtech could be different if its stops treating women as data. Feminist tech doesn’t have to be anti-tech. It just has to remember that technology is a tool, not a therapist. Empowerment should feel like care rather than compliance.

The future of women’s health shouldn’t have to rely on an aesthetic dashboard or premium subscriptions. It needs investment in real medical research, stronger privacy laws, and platforms that caters to women’s experiences.

Until then, Femtech remains as a system telling women to fix themselves, now inside an app and nice colours.

Because empowerment should not cost $24.49 a month.

References

References

Akiyama, S., Tanaka, E., Cristeau, O., Onishi, Y., & Osuga, Y. (2018). Treatment Patterns and Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs in Heavy Menstrual bleeding: a Japanese Claims Database Analysis. Journal of Medical Economics, 21(9), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1478300

Alfawzan, N., & Christen, M. (2023). The future of femtech ethics & privacy – A global perspective. BMC Medical Ethics, 24(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00976-z

Bach, W., & Wasilczuk, M. (2024). Pregnancy as a crime: A preliminary report on the first year after dobbs. Pregnancy Justice. https://www.pregnancyjusticeus.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Pregnancy-as-a-Crime.pdf

Borghese, B., Sibiude, J., Santulli, P., Lafay Pillet, M.-C., Marcellin, L., Brosens, I., & Chapron, C. (2015). Low birth weight is strongly associated with the risk of deep infiltrating endometriosis: Results of a 743 case-control study. Public Library of Science, 10(2), e0117387. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117387

Brodkin, J. (2025, August 5). Meta illegally collected data from flo period and pregnancy app, jury finds. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/08/jury-finds-meta-broke-wiretap-law-by-collecting-data-from-period-tracker-app/

Cole, A. C., Devan. (2023, November 6). Abortion law state map: See where abortions are legal or banned. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/us/abortion-access-restrictions-bans-us-dg

Dhar, P. (2024, May 29). Privacy remains an issue with several women’s health apps. Science News. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/privacy-womens-health-apps-tracking

Dixon, S., Keating, S., McNiven, A., Edwards, G., Turner, P. J., Knox-Peebles, C., Taghinejadi, N., Vincent, K., James, O., & Hayward, G. (2023). What are important areas where better technology would support women’s health? Findings from a priority setting partnership. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02778-2

Dubiniecki, A. (2024, November 14). Post-Roe, your period app data could be used against you. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/abigaildubiniecki/2024/11/14/post-roe-your-period-app-data-could-be-used-against-you/

Facca, D., Hall, J., Teachman, G., Redden, J., & Donelle, L. (2025). Femtech in context: A critical conceptual (re)view. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634593251371327

Flo. (n.d.). Flo privacy policy. Flo.health. https://flo.health/privacy-policy

Flo. (2024, October 4). What is included in flo premium? Flo. https://help.flo.health/hc/en-us/articles/360042141812-What-is-included-in-Flo-Premium

Flo. (2025). Is Flo safe to use? Plus other Flo data protection questions answered. Flo.health. https://flo.health/flo-privacy-faqs

Flo . (2022). welcome to flo, where your cycle is our priority. Facebook.com. https://www.facebook.com/61555783298983/videos/1289116009559639/

Foxter. (2025, September 5). Flo app class action lawsuit reveals shocking data privacy breaches. Kbsd6. https://kbsd6.com/global/flo-app-class-action-lawsuit-reveals-shocking-data-privacy-breaches/

Friedman, A. B., Bauer, L., Gonzales, R., & McCoy, M. S. (2022). Prevalence of third-party tracking on abortion clinic web pages. JAMA Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4208

Ganle, J. K., & Dery, I. (2015). “What men don’t know can hurt women’s health”: a qualitative study of the barriers to and opportunities for men’s involvement in maternal healthcare in Ghana. Reproductive Health, 12, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0083-y

Gu, Y., Zhou, G., Zhou, F., Li, Y., Wu, Q., He, H., Zhang, Y., Ma, C., Ding, J., & Hua, K. (2022). Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes in PCOS: Implications for Women’s Health. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.808508

Haider, A. (2025, March 4). 20 ways the trump administration has already harmed women and families. National Partnership for Women & Families. https://nationalpartnership.org/20-ways-the-trump-administration-has-already-harmed-women-and-families/

Hatmaker, T. (2022, July 8). Congress probes period apps over abortion privacy concerns. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2022/07/08/house-oversight-letter-abortion-period-apps-data-brokers/

Healthcare Readers. (2025, May 10). Top 25 femtech companies transforming women’s health in 2025. Healthcare Readers. https://healthcarereaders.com/insights/top-femtech-companies-products#google_vignette

Hendl, T., & Jansky, B. (2021). Tales of self-empowerment through digital health technologies: A closer look at “femtech.” Review of Social Economy, 80(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2021.2018027

Hofmann, D. (2024). FemTech: Empowering reproductive rights or FEM-TRAP for surveillance? Medical Law Review, 32(4), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwae035

Johnson, B. (2024). Femtechs take on women’s health. Nature Biotechnology, 42(6), 831–834. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02272-6

Keary, L. (2024, March 15). The 9 best fitness trackers, tested by our fitness and tech experts. Men’s Health. https://www.menshealth.com/fitness/g60175762/best-fitness-trackers/

S, J. (2025, August 18). Great jeans or great genes? Sydney sweeney’s ad was never just about denim – NETS2001 writing on the web. Netstudies.org. https://wotw.netstudies.org/2025/08/18/great-jeans-or-great-genes-sydney-sweeneys-ad-was-never-just-about-denim/

Zokaityte, A. (2025). FemTech assets. Feminist Legal Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-025-09570-7