Have you ever considered a question: Is technology truly equitable? As a female university student who frequently uses social media, I once believed I could freely express my opinions and enjoy fair treatment on social media platforms. However, when I tried searching for my future career possibilities, the results consistently presented content tied to gender stereotypes—like “lists of jobs better suited for women.”

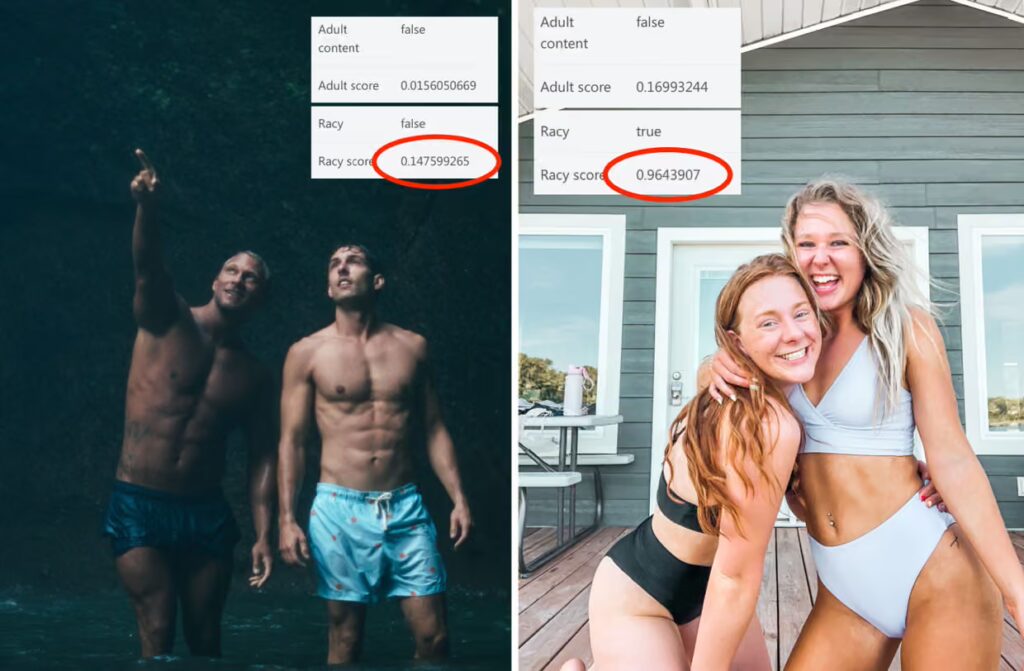

Take another look at the photos below. Do you think they are too revealing? These are two photos from LinkedIn, featuring two men and two women wearing swimwear. However, in these two photos showing both genders in swimwear, Microsoft’s tool classified the photos of the two women as pornographic content, assigning them a 96% rating. The mens’ photo, on the other hand, was classified as non-pornographic content, scoring 14%. The women’s photo received 8 views within an hour, while the man’s photo garnered 655 views. This suggests the women’s lingerie photos were either blocked or covertly restricted.

Based on this series of phenomena, I began to consider: Why did this series of unfair situations happen? Will it be resolved?

In fact, this is largely a consequence of algorithmic mechanisms. Such technologies cause social media not to lessen the feeling of gender inequalities, but to enhance them. With regard to intelligent social communications, algorithms represent the fundamental logic and essence of social networks. It is obvious that intelligent algorithms can improve user experience and validity of users in that they automatically push on the user content which, from their activities and preferences, users may find interesting (Keller et al, 2024). However, this also inadvertently increases the risk of pushing content that perpetuates gender inequality.

In recent years, several scholars have conducted tests on the algorithms of various social media platforms. In 2024, the University College London and the University of Kent jointly conducted a study on the algorithm of TikTok, one of the social media platforms. The results of the research showed that the algorithmic mechanism TikTok could quadruple the amount of misogynistic content pushed to users in five days. The algorithmic recommendation systems of social media affect both the content producers and receivers of information. The biases of its algorithms create unequal dissemination of information and discrepancies in the availability of information, which invariable combine to reinforce the gender inequality stereotype and do deeper injury. Fortunately, this phenomenon has already attracted the attention of official institutions and professional scholars, who have begun exploring how to effectively address gender bias on social media.

Algorithms are not self-generated; they are researched and developed by humans. Humans first generate, collect, and label the data that constitutes the dataset. Next, people decide which datasets, variables, and rules the algorithm will learn from and use for predictions. Throughout this entire process, it is evident that humans play a dominant role in the creation of algorithms. However, a set of data indicates that women make up only 22% of the workforce in the field of AI science. This highlights the fact that most algorithms are developed based on male perspectives. While it cannot be assumed that all male research and development workers harbor gender-biased thinking, it certainly cannot be assured that men are entirely free of any notions regarding gender inequality. On this basis, and because the generation process of algorithmic systems is not entirely transparent, this indirectly leads to gender bias in algorithms.

So how do inherently biased algorithms subtly reinforce gender inequality? For social media content creators, every piece of content that they post on social media undergoes analysis by artificial intelligence algorithms. These algorithms determine whether the content meets the platform’s publishing standards, which posts should be amplified, and which should be restricted. This is essentially a manifestation of “shadow banning.” Shadow banning is a content moderation technique social media platforms allegedly use for censorship. This means social media platforms can control the reach of posts. If shadowbanned, their posts will not appear to any followers or potential new audiences and only a very small number of people will see them. However, shadowbanning operates with very low transparency, and users are often restricted without their knowledge.

Algorithms not only control who gets heard but also dictate what people should see. If a man and a woman simultaneously pick up their phones, open the same popular social media app, and search for the same keyword, the results they find will be different. This disparity often manifests more clearly in keywords like “career,” “dating,” and “marriage.” A study examining gender bias on social media found that when presenting content, women’s names are typically linked more closely to family-related terms than career-related ones, and more frequently associated with arts than science (Fosch-Villaronga et al., 2021). For instance, searching “cooking” yields results heavily skewed toward female users, while searching “techonology” presents results favoring male users. Within this context, when users repeatedly encounter such gender-biased content on trusted social media platforms, societal inequality subtly intensifies (Fosch-Villaronga et al., 2021).

In the age of new media, traffic from social media represents the core goal of both platforms and creators. Besides, algorithms steer that traffic as it moves. According to the attention economy, content that has high emotional value tends to win the higher favor of the algorithm, as this is congruent with the core mission—maximizing user dwell time and frequency of interaction. Within gender-related topics, content that provokes opposition—such as anger, shame, or moral anxiety—highly meets the criteria for high-emotion content. Users often find themselves passively participating in the algorithm’s default emotional “competition” without fully understanding its mechanics. With this process, users believe they are being resistant or speaking out, but in fact they are being utilized by platform technology. These emotions are further transformed into the core products of the attention economy with commercial value, such as brand advertising placements and live-stream tipping.

Setting aside the influence of traffic, it has been shown that algorithms learn independently through the data sets created by human behaviour (Ho et al., 2025). In other words, if the greater part of the material that is introduced to users on social networks tends to reinforce the idea that men are best qualified to be leaders of companies, while men are better suited to control households, the algorithm will adopt this attitude and subsequently develop into a system with gender bias. Moreover, it should be noted that if users themselves have gender-unequal beliefs, they prefer to dwell a longer time on products which continue the gender bias theory. When the algorithm detects this pattern, it further recommends similar content to the user. In this process, gender bias is perpetuated through individual users’ discriminatory tendencies.

Summarizing this whole process reveals that the gender bias stemming from social media algorithms has actually created a vicious cycle, with each component interconnected and interacting with one another. First, algorithms inherently carry a certain degree of bias due to their underlying mechanisms. At this stage, the gender bias value is only in its initial phase and does not significantly exacerbate gender inequality. Then, to cater to today’s traffic patterns and gain more exposure, content creators have been compelled to deliberately produce material featuring gender conflicts. At the same time, creators—especially female creators—have been silenced and suppressed by algorithmic shadow banning, preventing them from sharing authentic female perspectives and their genuinely gendered content. In order to elude any traffic suppression and public outrage, this material has been supplanted by inauthentic portrayals. As a result, controversial content as biased content, on social media platforms has begun to spread and proliferate. The metrics of gender bias on social media began slowly increasing. Next, users start to unwittingly encounter recommended content with suggested signals of gender inequity. Given the characteristics of the traffic-driven era and the opacity of algorithms, most users judge whether to trust content based on its metrics rather than through rational deliberation. Users routinely engage with content that has a high attraction value by liking, commenting on, and sharing it. This interaction helps to further increase the reach of gender biased content, while algorithms recognize this as popular content and increase traffic. At this moment, the algorithm pushes to users more similar content while learning from the biased data, allowing the gender bias value to increase rapidly. Within this insulated, closed loop, due to the nature of the algorithm, consumers and content producers become intertwined. Thus reinforcing and effectively driving the gender bias value to the peak.

Inequity in gender on social media goes beyond just creators and users, and has wide-ranging and deep repercussions. In today’s digital age, many teenagers’ lives are lived on social media. The incredibly upsetting and distressing thought of moving from childhood to adulthood, almost entirely saturated with the negative effects and bias of gendered social media algorithms, is truly saddening. But it is happening. According to UNESCO, many girls are now being subjected to algorithmic image-based content on social media sites, including pornography and videos premised on unhealthy behaviors and unrealistic bodies. This has the potential to have devastating negative impacts on girls’ self-esteem, body image, mental health, and general well-being. A Facebook study found that 32% of teenage girls reported feeling worse about their bodies after viewing Instagram content when they were already dissatisfied with their appearance.

Beyond these effects, such biases also influence women’s employment prospects, with their impact gradually emerging as early as adolescence. According to statistics, women account for less than 25% of professionals in science, engineering, information, and communication technology fields. The roots of this phenomenon can be traced back to students’ formative years. Girls are guided by negative gender norms amplified on social media platforms during their school years, leading them to believing fields like science, engineering, and mathematics are male-dominated. By the time they enter the job market, algorithmically manipulated job advertisements automatically filter out positions in these sectors from their searches. Moreover, unconscious gender biases in corporate screening processes often result in male candidates being prioritized (Lim, 2022). Additionally, women’s visibility and expression on social media often expose them to risks of hate and harassment (Lim, 2022). This potential for online backlash and violence forces them to alter their online speech, thereby compromising their fundamental rights of free expression.

Breaking through the biases of social media algorithms requires a concerted effort from society as a whole—a journey that is bound to be long and arduous. Zinnya del Villar, a leading expert in responsible AI, shares insights on the challenges and solutions in a recent conversation with UN Women. She emphasized the need to ensure diversity in the data used to train artificial intelligence systems. This means actively selecting data that reflects different social backgrounds, cultures, and roles which encompasses all genders, races, and communities, with particular attention to marginalized groups. Algorithmic intelligence systems should not merely understand traffic rules; they must also incorporate explicit gender expertise. Only then can we ensure that gender discrimination does not become the price paid for generating traffic. Certainly, here one of the very important significations within legacies is the fact that development teams influence the display of AI algorithms. It is thus pertinent that diversity, equity, and inclusion are reckoned with as far as the astrologically inclined human beings in all levels of operations are concerned. As Smith and Rustagi (2021) noted in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, developers must genuinely recognize that data and algorithms are not neutral to fully integrate gender equality considerations into AI. So what can most of us—social media enthusiasts—actually do? It’s simple: just remind yourself that social media algorithms can be biased, and don’t blindly trust or follow the content they want people to see!

Gender equality has become a matter of high global concern. “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” is the fifth of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Only when algorithms truly become bridges for dialogue can gender issues be discussed rationally, and only then can gender equality be genuinely achieved!