Over time, the film industry has undergone notable changes, not just in technological improvements, but also in significant shifts in storytelling, pacing, and editing. Going to the cinema used to be a luxury when films were released specifically only as a theatrical release, and in some cases, after their initial theatrical release, a DVD release would follow. Whereas, in recent times, audiences are able to access visual media via a multitude of ways due to the rise of streaming services. This shift in how we access and consume our media has affected the audience’s attention spans.

Gaining viewers has become increasingly harder as audiences are able to consume a vast amount of content in a short amount of time. Consequently, filmmakers have been compelled to recalibrate cinematic form to align with the fragmented viewing habits of the digital age. Today’s audiences have been conditioned by the rapid tempo of social media feeds and streaming platforms1 . Audiences are now expecting constant stimulation, quick edits, and familiar content that demands little cognitive effort to follow2 .

Our modern viewing habits are a reflection of the culture of immediacy that social media has fostered in us3 . A simple way to gain an audience in the film industry has been to release sequels and capitalise on their pre-existing fan base, who often continue the story from that universe4 . Film companies are banking on the familiarity of the movie franchise to ensure that the prior audiences continue to have the audience’s engagement. Another way the film industry is capturing the audience’s attention span is through the increase in faster pacing and editing5 . Society has seen a reduction in its overall attention span, and film studios are noticing this shift. In order for them to continue competing in this economy, they have redesigned movie expectations.

Film has been known to reflect what we know as reality; thus, film mirrors the changes in the cognitive and emotional demands of audiences. As James E. Cutting6 puts it, “popular films have become mind candy”7, designed to satisfy the modern viewer’s appetite for stimulation. A research conducted by James E. Cutting revealed a steady decrease in the average shot duration from 1915 to 20158. It can be argued that this is due to the technological advancements throughout the years; it also illustrates the deliberate adaptation to the audience’s shrinking attention spans. The rise of social media use has also intensified this trend of reducing attention spans. Social media platforms, such as TikTok, have evolved into tools that reward quick, habitual engagement through metrics like the streaks you gain when you consistently send TikToks to friends in the app. As everyday media consumers often shift towards using social media as a content source, they are increasingly choosing not to watch films as a pastime. Social media has trained audiences to prefer emotionally efficient, low-focus experiences, which in turn has influenced modern film pacing and structure9.

Earlier cinema relied on slower pacing and extended shots to encourage emotional reflection and narrative absorption. In contrast, contemporary film editing trends feature an abundance of rapid cuts, intensified motion and fluctuating luminance to sustain attention through constant sensory engagement. This stylistic evolution reflects not only changing aesthetic preferences but also a cognitive recalibration of audience preferences10. To ensure that audiences are gained, studios will reflect what the audience wants through the editing and pacing of the film.

The acceleration of pace is also a reflection of the changes in emotional engagement resulting from reduced attention spans, due to the prevalence of social media and short-form content. With social media constantly feeding us with dopamine hits, audiences are constantly chasing that instant gratification11. Films are needing to adapt their pacing to ensure that audiences are continuing viewing. Thus, they change their editing rhythms to match the viewer’s affective state12. The relationship between pacing and attention thus forms a feedback loop. As audiences get used to and crave rapid, almost immediate information flow due to social media use, filmmakers increase visual stimulation to maintain engagement. In turn, these fast-paced films further engrain the accelerated storytelling in viewers’ minds. The changes in the film industry are not only due to technological innovation, but it is also due to the cognitive shifts of audiences as a whole. The craft of filmmaking, which was once centred on narrative immersion, has evolved into a calibrated exercise in attention management.

In the film industry across the years, there has been the emergence of franchise-based and multi-part storytelling in films. While this trend is partly driven by the adaptation of multi-part narratives, such as Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame. It also more deeply reflects how the industry has responded to audiences with increasingly shorter attention spans. Having split a full story across multiple films allows the studios to end each film with a big cliff-hanger that will capture the audience’s attention for longer.

Sequels have also seen a rise in popularity, as they provide an immediate sense of familiarity and cognitive ease by offering audiences pre-established characters, worlds, and emotional attachments that demand little interpretive effort and require less active processing13 14. This rise of sequels follows an overarching pattern in the attention economy where consumers are gravitating toward familiar content to ensure they derive a sense of instant gratification15.

Basuroy and Chatterjee16 conducted a study that examined the profitability of sequels and original films. It was found that the sense of familiarity sequels provide to audiences boosts revenues and reduces risk compared to original films17. This study also found that Hollywood appeared to be depending on quick-release sequels to maintain profitability18. Sequels can be seen to be successful as they capitalise on the pre-existing fan bases, which then allows studios to minimise the uncertainty attached to releasing an original film1920. Sequels capture the original fanbase and the diehard fans who would watch anything related to their favourite story, thus these audiences require less attention span to digest the new media.

Similarly and more recently, another study by Pokorny et al.21 found the same pattern to be true. It found that sequels are integral to Hollywood’s business model as they are its safest and relatively quick means of generating profits22. Creating a franchise from a cinematic universe provides a safety net of a predictable audience base23. Although sequels appear to be the most optimal business move, it does reduce the cognitive and emotional barriers associated with viewing and comprehending a new narrative24. When audiences are drawn to the comfort of recognising the storyline, characters or world, they are demanding less mental effort25.

In a saturated media environment, novelty requires cognitive investment and emotional risk, which can deter audiences in the new economy as they have limited time to spare. With all the new and constant media surfacing, audiences are gambling with their time to view original films. Often, viewers do not want to engage with media that they will not enjoy; thus, they tend to drift toward content that they know will provide them with dopamine. Knowing they will gain instant gratification from sequels to a franchise they already enjoy becomes the safer option, given their limited attention spans.

Along with many other moviegoers, we are speculating that the film industry is releasing reboots, sequels and remakes as quick cash grabs. The big franchises that come to mind are Star Wars, Fast and Furious and Disney. When a beloved franchise such as Star Wars adds expansions to its universe, critics, by nature, tend to break down every aspect of the films, when the expansion often fails to capture the initial spark of the original.

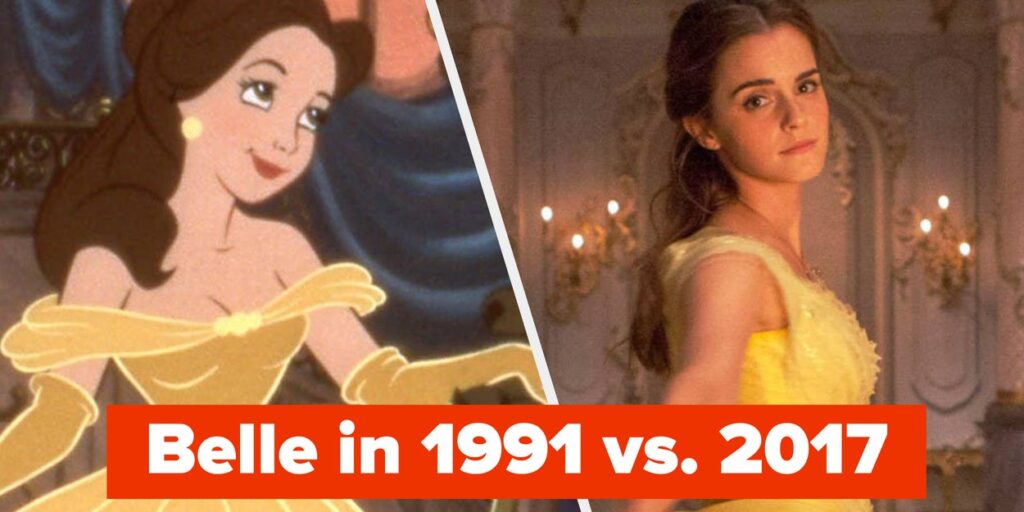

It has become common knowledge that, in particular, Disney’s princesses are getting unwanted live action remakes . As Afeworki puts it, “they do not add substantial value to the story world”. These attempts seem to be an attempt to recreate the Disney spark from the early stages of animation for a new generation. While trying to recreate that Disney magic, they are also gaining an audience from the original fan base, who view these films from a nostalgic perspective.

The Fast and Furious franchise is also guilty of rehashing old storylines to continue generating revenue. Although they are not currently remaking the films, they are creating an extended universe with its many sequels, as well as side movies featuring characters from the main movie line. It is a beloved franchise that many fans are happy to see continued, but following the unfortunate passing of Paul Walker, many of the Fast and Furious films have been perceived as cash grabs. It feels like the films are just continuing the franchise because they generate quick cash. The more recent films have lost the initial anti-hero underdog feeling. It has become more extravagant in the stakes and storyline.

Sequels also bring a sense of nostalgia to viewers. Cheung et al.26 argue that we anticipate nostalgia because it often increases social connectedness, and even at times, life meaning. With film sequels, audiences not only revisit beloved franchises to relive past enjoyment but also to participate in an ongoing cultural narrative2728. Like much of pop culture, participation in fan culture is expected to eventually become nostalgic, thereby reinforcing a deeper level of engagement with pre-existing media, which in turn leads to shrinking attention spans29. Moreover, anticipated nostalgia30 encourages audiences to emotionally reattach to familiar cultural experiences, which do not require as much attention to comprehend, thereby inadvertently contributing to the reduction of the attention span problem. Thus, the rise of sequels reflects both industrial adaptation and psychological adaptation. Sequels mitigate financial risk for film studios and offer cognitive comfort and emotional continuity for viewers/fans.

Nostalgia thrives in short, repetitive doses that the film industry can exploit as a tool for studios to instantly evoke emotion without requiring narrative complexity or long attention spans. According to Zhou et al.’s31 study, participants reported a sense of increased happiness when recalling their past. This suggests that nostalgic media experiences can engage audiences quickly, even amongst fragmented attention spans. Zhou et al.32 highlight that nostalgia can provide psychological satisfaction without effort. This parallels the film industry trend of sequels and reboots. Audiences are preferring predictable, familiar narratives that don’t require prolonged focus as they are emotionally efficient33. Thus, the film industry is utilising nostalgic sequels to succeed in the modern attention economy because they effectively deliver emotional connections.

As the attention economy has conditioned audiences to expect constant stimulation and instant emotional reward, this has seeped its way into the film industry. In our modern digital era, audiences have been inundated with unprecedented levels of information and entertainment options, resulting in fragmented attention and influencing how we engage with media. The changes to the film industry can be attributed to the result of social media being a platform that overstimulates users with an influx of options; therefore, we are unable to focus on a singular piece of media34. A study in 201835 found that social media overloads its users with information and provides continuous media exposure in short, concentrated periods36. All industries are competing for consumers’ attention; therefore, there is a demand for sensory engagement, which films have been required to adapt to in order to maintain profitability3738.

Modern cinema and the film industry as a whole continue to draw from real life for production ideas. However, with our limited attention spans, they are now shifting their production style to capture the audience’s attention. They achieve this by having fast pacing combined with the psychological comfort of sequels and franchise narratives. Utilising these enables films to maintain audiences cognitively hooked. Thereby, they result in a film landscape that prioritises accessibility and immediacy over complexity and patience. The future of cinema will likely depend on how filmmakers strike a balance between commercial demands and the director’s artistic integrity. However, analysing current markets, it is expected that there will be a continued chase for the audience’s fleeting attention by using nostalgia, faster cuts and/or reuse of the same storyline.

Footnotes

- Jacobsen, B. N., & Beer, D. (2021). Quantified Nostalgia: Social Media, Metrics, and Memory. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008822 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Jacobsen, B. N., & Beer, D. (2021). Quantified Nostalgia: Social Media, Metrics, and Memory. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008822 ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Cheung, W.-Y., Hepper, E. G., Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2020). Anticipated nostalgia: Looking forward to looking back. Cognition and Emotion, 34(3), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1649247 ↩︎

- Basuroy, S., & Chatterjee, S. (2008). Fast and frequent: Investigating box office revenues of motion picture sequels. Journal of Business Research, 61(7), 798–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.030 ↩︎

- Pokorny, M., Miskell, P., & Sedgwick, J. (2019). Managing uncertainty in creative industries: Film sequels and Hollywood’s profitability, 1988–2015. Competition & Change, 23(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418797302 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Cheung, W.-Y., Hepper, E. G., Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2020). Anticipated nostalgia: Looking forward to looking back. Cognition and Emotion, 34(3), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1649247 ↩︎

- Zhou, X., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Gao, D.-G. (2008). Counteracting Loneliness: On the Restorative Function of Nostalgia. Psychological Science, 19(10), 1023–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x ↩︎

- Zhou, X., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Gao, D.-G. (2008). Counteracting Loneliness: On the Restorative Function of Nostalgia. Psychological Science, 19(10), 1023–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x ↩︎

- Jacobsen, B. N., & Beer, D. (2021). Quantified Nostalgia: Social Media, Metrics, and Memory. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008822 ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Carstens, D. S., Doss, S. K., & Kies, S. C. (2018). Social Media Impact on Attention Span. Journal of Management & Engineering Integration, 11(1), 20–27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-media-impact-on-attention-span/docview/2316725647/se-2. ↩︎

- Cutting, J. E. (2016). The evolution of pace in popular movies. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0029-0 ↩︎