With risqué lyrics, revealing outfits, and signature bombshell blonde curls, American pop singer Sabrina Carpenter has quickly cemented her status as one of the most prominent – and controversial – celebrities in the contemporary music scene.

In June this year, the former Disney star faced controversy over her 2025 Man’s Best Friend album cover, which features a faceless man gripping her hair as she poses on all fours and seductively glances at the camera. The cover sparked heated debate amongst fans, feminists, and everyone with a phone. In fact, weeks later, Carpenter released an alternate cover design, joking that it was “approved by God”. But Carpenter’s image extends beyond her album cover. Her provocative onstage dance moves, short, skin-tight and sparkly outfits, and playful, hyperfeminine aesthetic have provoked public – and primarily online – discussions about her public image, and its inexplicable ties to feminist ideas.

Indeed, critics disagree about Carpenter’s status as a feminist symbol. But feminism isn’t a static notion. According to Sara Strauss (2023), it shifts according to contemporary social, historical and political climates. In fact, Strauss continues that contemporary so-called “fourth-wave feminism” attempts to “mobilise women’s joint power”, which Carpenter attempts to do, with her curated image a reclamation of sexual power.

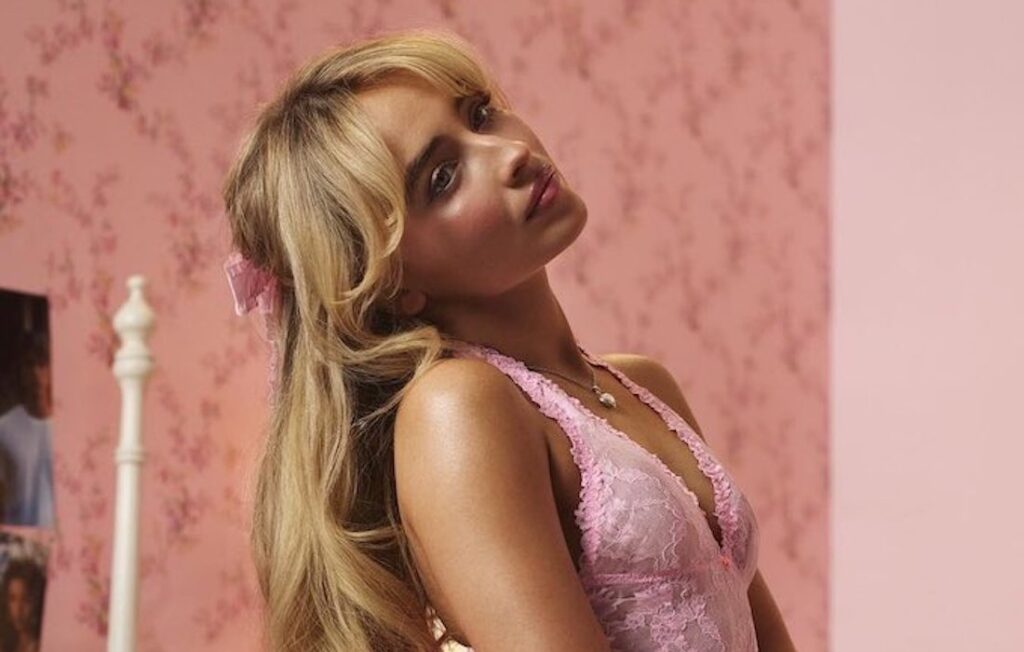

Furthermore, Panizza Allmark (2021) discusses “postfeminism” and “neoliberal feminism” as concerning female choice, empowerment and agency, with these ideas often commercialised. From these discussions, Carpenter certainly champions a new wave of modern feminism by actively controlling and owning her overtly sexual public image, promoting women’s expressions of sexual freedom. Carpenter appears to have more agency in her image (and sexuality) than the public credits her with – but that doesn’t mean her image isn’t up for dispute.

Mark Dixon (2019) explores Stuart Hall’s concepts of “encoding”, “decoding” and “Reception theory”, where audiences interpret media products in different ways due to personal experiences. Hall discusses that differing audience contexts mean audiences may not understand media objects’ meanings exactly as media producers intended. Certainly, these concepts link to the public’s differing responses – contempt, praise or something in between – to Carpenter’s highly sexual image.

Dixon (2019) first discusses Hall’s “Oppositional readings” concept, where audiences experience conflict with or reject the media producers’ intended message. Oppositional reading responses become clear with Carpenter’s explicit portrayal of her sexuality – on both the album cover and through her persona – noted by some as inappropriate, degrading, and promoting sexist ideas. Melissa Wheeler (2025) discusses how audiences may see Carpenter’s cover as pornographic and degrading, and Louis Staples (2025) agrees, claiming Carpenter’s cover views women as merely sexual objects for “male gratification”.

These reactions suggest Carpenter’s sexual image creates a ‘male fantasy’ and reinforces ideas of patriarchal submission. As Carpenter appears quite literally at the foot of the man in the cover, the public clearly interprets Carpenter’s album cover and her constructed image as anti-feminist.

These concerns are directly linked to Allmark’s (2021) conversation on how female popstars may adhere to patriarchal ideas of femininity, which sees women as “submissive, innocent and childlike” yet “sexually available”. These patriarchal ideas are misaligned with this audience’s interpretation of feminism, with Carpenter’s attempts to use irony in her image further provoking conflicting responses from the public.

Carpenter claims to use irony and humour to promote her image and albums, but some suggest her use of satire isn’t so obvious or is distasteful. Paul Glynn (2025) noted Emily Bootle’s remarks that Carpenter “knows sex sells”, but this doesn’t mean Carpenter’s music is clever, or that she is a feminist. Further, as Carpenter blatantly poses like a dog on the album cover, Conor Murray (2025) explains how Glasgow Women’s Aid, a group supporting women experiencing domestic violence, saw Carpenter propagating “tired tropes” that objectify women in framing them as “pets, props and possessions”.

“The album is not for any pearl clutchers.” – Sabrina Carpenter, BBC

Certainly, this audience rejects Carpenter’s attempts to flippantly portray herself as a literal ‘man’s best friend’. Instead, Carpenter is believed to propagate unhealthy ideas of feminism and sexual objectification. This audience opposing Carpenter’s intended message has ties to Allmark’s (2021) argument that “hyper-sexualisation” of the female body impedes the aims of feminism. It also reflects what Hall, through Dixon (2019), labels as “misreading”, with a lack of context or information hindering audience interpretations. This is because this audience misinterprets Carpenter’s persona as sexually submissive instead of purely satirical.

On the other hand, Dixon (2019) refers to Hall’s discussion of “Dominant readings”, where audiences agree with and acknowledge the media producers’ intended media message. Accordingly, others discuss Carpenter as a feminist, embracing her sexual empowerment. Wheeler (2025) suggests that Carpenter may use sexuality in her album cover to emphasise women’s control and ownership of sexual power. Jade Hayden (2024) agrees, stating that Carpenter actively chooses to dress cheekily in lingerie, and doesn’t want to have “sex with you”, but rather wants to “have sex…and you’ll be there too”.

“When I started becoming more sexual as a person, I think it’s just something that’s a part of life. You want to write about it.” – Sabrina Carpenter, CBS Mornings

Carpenter’s image, therefore, predicates her own sexual desire. Carpenter’s sexual expression then connects to Allmark’s (2021) discussion, where celebrities like Beyoncé and Lady Gaga present their body as a site for female pleasure and power. Audiences therefore agree that Carpenter is liberated through her excessive portrayal of sex. Therefore, this audience understands what Hall, through Dixon (2019), discusses as intended “dominant cultural messages” in Carpenter’s album cover and image. Consequently, these audience members then delve deeper and consider her use of irony.

Katrina Muller-Townsend (2025) discusses how Carpenter plays with irony in her sexual public persona to “mock industry norms”. This aligns with audiences’ discussions that Carpenter uses irony to critique patriarchal power structures. Markiel Magsalin (2025) notes how Carpenter explicitly parodies “the male gaze” on her album cover, but decreased media literacy levels online mean audiences misinterpret Carpenter’s position ‘on all fours’ as sexual disempowerment.

Arwa Mahdawi (2025) echoes this thought by discussing how one user was concerned that people couldn’t recognise Carpenter’s clear critique of patriarchal views of women, since Carpenter’s first track on Man’s Best Friend is named Manchild. These opinions reflect how this audience aligns with Carpenter’s satirical media messages. They understand how Carpenter exaggerates male sexual domination and female submission as a wider social critique of patriarchal structures.

This audience understanding reflects Dixon’s (2019) discussion of Hall’s dominant reading concept, where audiences “knowingly decode texts” the way they were intended. In this way, this audience sees Carpenter act according to postfeminist movements, aligned with Allmark’s (2021) exploration of how contemporary female celebrities may use their voice to champion feminist causes.

Clearly, Carpenter’s image frames her as either anti-feminist or feminist. However, from these discussions, it becomes evident to me that Carpenter’s overtly sexual image, which she owns and controls, frames a new wave of modern feminism. This new ‘era’ allows women to express their sexual freedoms, with this point arising firstly through Carpenter’s resistance to traditional patriarchal binaries.

Carpenter’s public image breaks free from adherence to the traditional patriarchal binary of the pure ‘good’ girl or the ‘bad’ sexual girl, which reflects notions of modern postfeminism. Discussed by Rotem Kahalon et al. (2019) as the “Madonna-whore dichotomy”, women are categorised as ‘good’ if they’re pure, virgin “Madonnas”, or ‘bad’ if they’re provocative and “seductive ‘whores’”. Kahalon et al. continue that whilst men are expected to desire sex, the restrictive binary forces women to internalise shame about their sexual desires.

“I’ve never lived in a time where women have been more picked apart and scrutinized in every capacity. I’m not just talking about me. I’m talking about every female artist.” – Sabrina Carpenter, Rolling Stone Magazine

These definitions are especially ironic given that Magsalin (2025) notes how another pop music icon, Madonna, has had her career scrutinised. She remarks that Madonna embraced sexuality as a means of expressing her power and was met with “pearl-clutching critiques”. As expected, then, like Madonna, Carpenter is classified in this binary by the public. Indeed, Melissa Fabello (2025) discusses that those chastising her album cover claim “purity culture” is necessary to women’s “liberation” from the patriarchy.

But sexual liberation also frees women from patriarchal structures, which is exactly what Carpenter aims to do. She blurs the strict lines of women’s purity and impurity as inscribed by the patriarchy, and instead publicly models her own desires. Along the way, she urges her young female Gen Z audience to embrace a more positive perception of sexuality – where sexual desires aren’t repressed.

Carpenter’s performances are proof of this. Hayden (2024) considers her 2025 BRITs performance, where she mimics sex positions when dancing, and also sings highly sexual outros to her song Nonsense onstage. Amelia Chapman discusses this further, noting Carpenter’s sexual dance positions when performing her song Juno.

In this way, Carpenter appears to portray modern feminist thought, as Kahalon et al. (2019) discuss modern feminism as an age where women are “ambitious”, “unapologetic”, and are in “control” of their sexuality. As such, Carpenter isn’t ashamed of her sexuality; she is proud, and she urges her audience to feel the same. Carpenter also urges audiences to consider the construction of her sexual persona.

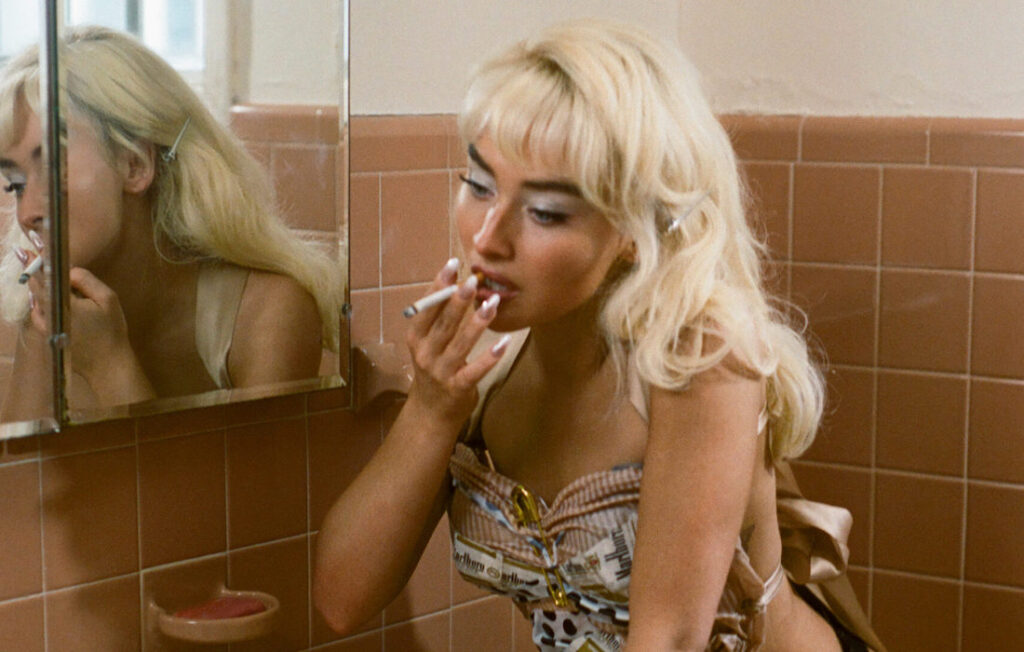

Carpenter performs and parodies hyperfemininity and sexuality through her public persona, which allows her to critique patriarchal structures and channel notions of modern feminism. This becomes evident most clearly through her physical image.

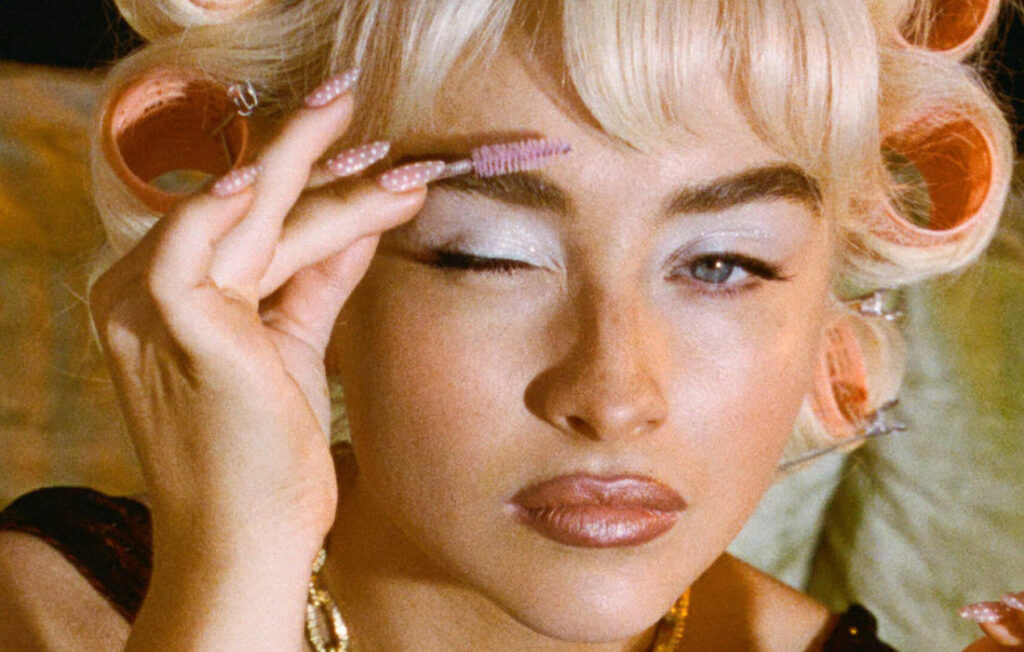

Brooke Ivey Johnson (2025) considers Carpenter’s heavy, feminine eye makeup, thick eyelashes, bright lipstick and short babydoll dresses. She states they take inspiration from drag and camp aesthetics, with Carpenter parodying traditional femininity. Furthermore, Alyssa Bailey (2025) interviews Carpenter, with Carpenter remarking that her onstage “shows” can feel like she’s “playing a character”.

These discussions reflect how Carpenter’s image, appearance and costuming become a performance of exaggerated patriarchal femininity and beauty ideals. Judith Butler’s concept of “gendered performance” that Jacqueline Lambaise (2003) discusses then becomes useful, with gender based on people’s actions. Indeed, as Butler discusses, Carpenter constructs an image that is a performance – a performance she actively orchestrates.

Agency, a key aspect of postfeminist thinking, therefore, becomes significant. Carpenter actively creates and crafts her persona. A constructed persona, then, as Johnson (2025) explores, makes audiences aware of how femininity is “consumed and commodified”. Carpenter perfectly executes her performance of playing the innocent-looking, but overtly sexual and hyperfeminine figure. But she is in control. Carpenter, in turn, mimics rebellious feminist and sexual icons such as Madonna, who Allmark (2021) claims challenged patriarchal ideas by embodying a feminine, sexual persona that she had complete agency over.

Therefore, Carpenter’s exaggerated aesthetic and performance reflect a new shade of modern feminism to audiences. She creates the image of the female celebrity that Allmark (2021) discusses – a “provocative woman” that is both “pleasurable and powerful”. However, Carpenter’s aim of presenting this image may be undermined by public misconceptions.

Public misconceptions of feminism categorise Carpenter as anti-feminist; however, according to accurate definitions of modern feminism and postfeminism, Carpenter’s image appears to champion female and sexual empowerment. This becomes evident as both Mahdawi (2025) and Rebekah Hendricks (2025) critique Carpenter’s album cover, claiming it is designed to serve the male gaze. These statements imply Carpenter is at the ‘whim’ of the male figure in the cover. However, the term “the male gaze” is incorrectly used in these circumstances and has become a popular online buzzword.

“My interpretation is being in on the control… as a young woman, you’re just as aware of when you’re in control as when you’re not.” – Sabrina Carpenter on the Man’s Best Friend album cover, CBS Mornings

Shohini Chaudhuri (2006) remarks that Laura Mulvey coined “the male gaze” in 1975 to argue that the “controlling gaze in cinema is always male”, with audiences encouraged to view the “heroine” as a “passive object of erotic spectacle”. Carpenter’s fans are decidedly not male. Her audience is primarily young Gen Z women. She therefore constructs this image with her female audience in mind, and in her interview with Mel Ottenberg (2025), she explicitly states she wanted her album and sexual lyrics to shed light on the taboo nature of female sexual pleasure.

Additionally, common conversations of Carpenter’s album cover, such as those discussed by Magsalin (2025), suggest Carpenter is “setting women back”. However, postfeminism is characterised by Allmark (2021) as including a range of feminist freedoms. So, by Allmark’s definition, audiences may paint Carpenter’s image as regressive when she is actually freely championing her sexual and artistic freedoms. In fact, if Carpenter truly sets women back, as Magsalin (2025) discusses, this reflects more on the “fragility” of “modern feminism”. Carpenter instead embodies the strength associated with modern female empowerment.

As one of the biggest pop stars in the world, Sabrina Carpenter is redefining what it means to be a ‘feminist’ celebrity for modern audiences. Her carefully crafted public image centres on embracing female pleasure and sexuality, whilst subtly critiquing the patriarchal structures that underpin traditional femininity. Carpenter, therefore, embodies modern feminist movements in her curated image, with female sexuality not something to hide, but to celebrate.

Carpenter’s album is named Man’s Best Friend, but it should be said that she truly means Girl’s Best Friend, for Carpenter shows women can be both provocative and powerful.