The instant gratification of modern hyper-consumption is at its most powerful in fast fashion. Same-day delivery means that a shirt can be bought and arrive in as little as 24 hours. Swipe your fingers on a screen, pay a small price, and track the parcel on its way to you. It’s a simple, frictionless shopping experience that fast fashion retailers have mastered. But it is also the epitome of hyper-consumption, a system in which clothes are more disposable than durable.

Bonanni et al. (2024) defines fast fashion as “the reproduction of clothing that is rapidly produced by mass-market retailers at low cost.” Examples of these mass-market retailers include Missguided, Fashion Nova, Temu and Shein.

In the past, buying a few new pieces of clothing was a special occasion. Now retailers release hundreds of new styles every week. For example, Zara has 24 new collections every year. Fast fashion thrives on being affordable and easily accessible. You are able to order an item online and it can arrive to you within days, sometimes even the same day with express shipping. However, there is a hidden cost: slave labour and the destruction of the planet!

Exploitative and Dangerous Labour

We can see the social unsustainability of fast fashion in how workers are treated. An example of this is Prentice (2021’s) article about the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, which killed 1134 people and injured hundreds more. Engineers discovered cracks on the building a few days before the initial collapse and recommended that the building remain closed. But workers were told they had to return to work, or they would miss deadlines. Then at 8:45 am the building collapsed.

Attempts to unionise are regularly met with threats of dismissal or violence. According to ABC News (2014), in Cambodia, strikes in 2014 demanding greater pay were greeted with brutal crackdowns that killed and wounded many people. This culture of fear is a sign of a bigger problem. The violation of workers’ rights to safeguard the low-cost production model that keeps fast fashion successful. Brands also point to a lack of control over long and complex supply chains. They hire suppliers, who themselves sub-contract other firms to do the work, who then do not always maintain visibility over working conditions. This provides a shield for the fast fashion brands to carry on exploiting cheap labour without being held accountable for any negligence.

After Rana Plaza, Prentice (2021) found that compensation funds for the victims and families were slow to materialise, inconsistent, and calculated in a way to strategically avoid accountability. Outside of South Asia, exploitative practices still exist.

In 2020, investigators found out that in Leicester, England, garment workers for the fast fashion brand Boohoo were paid as little as £3.50 an hour, which is far below the legal UK minimum wage of £11.44 an hour for adults over 21, according to the National Living Wage. With a garment worker, Paramjit Kaur, telling BBC News reporters that “Working for £3 an hour made me feel dirty”. A large number of these workers were immigrants and, in some cases, undocumented, making them vulnerable to exploitation. The scandal exposed that the labour abuses of fast fashion were not isolated to the Global South, but systemic wherever vulnerable people can be exploited.

These examples illustrate that fast fashion’s affordability is made possible only by human exploitation.

Image of factory workers in China producing clothing for Shien. Source: ABC News

Environmental Impacts of Fast Fashion

Aponte et al. (2024) article states that the fast fashion industry is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. According to the EEA, it is the sector with the fifth-highest emissions across the whole supply chain. It also accounts for between 4% and 10% of total global emissions.

Resource Intensity

The human cost of fast fashion is incalculable, while the environmental costs are catastrophic. Fast fashion is now being identified as one of the greatest contributors to global environmental degradation. Ninety-two million tonnes of waste are produced per year and Seventy-nine trillion litres of water are consumed per year.

The problem starts with raw material extraction. Fast fashion is cheaply made with low-cost fibres such as polyester. Polyester is non-biodegradable, and each year 342 million barrels of oil are used for producing plastic-based fibres. According to European Environment Agency (2022) year, 14 million tonnes of microplastics have been polluting the environment. Each time polyester is washed it sheds microfibres, which go down the drain into rivers and seas, where they are eaten by fish, enter the food chain and are re-served up on our plates.

Cotton has always been seen as the natural alternative, when in reality, it is not much better than polyester. Cotton farming requires vast amounts of water. Producing a single cotton T-shirt takes on average 2,700 litres of water or the same amount of drinking water for one person for 900 days (2.5 years), according to WWF (2014). Although some alternatives do exist, such as organic cotton, which uses about 1,100 litres of water per t-shirt.

Waste Crisis

Besides how many resources go into making fast fashion, the size of the waste problem is equally outrageous. People today are buying 60% more clothes than they did 20 years ago, but keep each item for half as long, says Clean Up (2021). Put simply, when we have overstuffed wardrobes full of last season’s trends, we are more likely to chuck them out. We get new collections in online stores every week, and we have been conditioned to believe that jumper bought last month is already out of fashion, and you should feel guilty wearing it.

The clothes we throw away don’t just magically go away, of course. Ellysa Ignatescu Hot Take, titled “You’re better off throwing your clothes in the bin”, delves into how the fast fashion industry has us fooled into believing that in-store recycling bins are helping the planet, when most of those clothes end up in landfills.

Many of us find it comforting to stuff unwanted clothes into a bag and deposit it in a charity bin, in the illusion that we are recycling or donating them. The reality of what happens to a used item of clothing is much more complicated, and much less comforting.

It is said that every year in Australia, over 1.4 billion units of new clothing come onto the market, and every year, more than 200,000 tonnes of clothes wind up in landfills. Of course, it is only a tiny fraction of what is donated in the Global North that finds its way to local thrift stores. Africa, for example, receives 70% of all clothing donations made in Europe, according to Poerner (2020). Ghana, in particular, has been likened to ‘a death pit’ for fast fashion landfills. The Kantamanto Market in Ghana is said to be buried under clothing imports, much of which is unsellable due to being low-quality.

Image of a massive landfill in Ghana. Source: The Guardian

Pollution

Textile dyeing is a second issue. It is the second-largest polluter of water globally. Untreated toxic wastewater from dyeing facilities is released into rivers each year in countries like China, India and Bangladesh. According to Islam et al. (2025) thirty of 72 toxic substances that have been identified are irreversible, which increases the impact on the environment. This impacts not only the aquatic life in these waterways, but also the communities that depend on the waterways as drinking water.

In these communities, rivers are not a luxury. Rivers are life. They are a source of drinking water, fish to eat and water to grow crops. A river running red with dyes containing heavy metals, salts and toxins, is a river where farmers can no longer use the water to irrigate their fields. Their soil is contaminated, their crops dry up and their yields fall. Fish die, and children in fishing families have no food and no money. Local people suffer from skin diseases and respiratory infections from bathing in the water. Far from being about colouring clothes for consumers many thousands of kilometres away, it becomes a reality in the lives of those who live next to the garment factories.

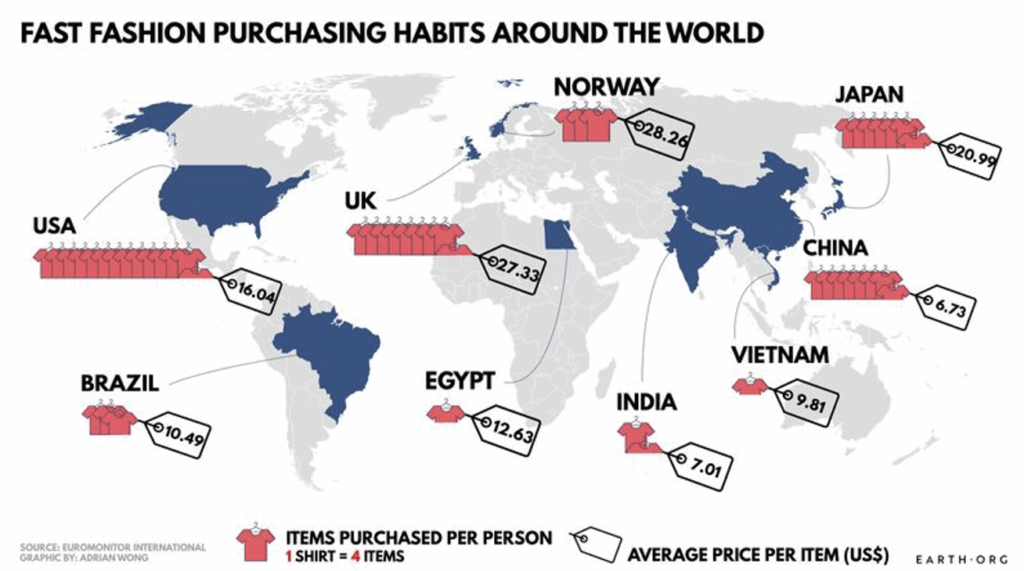

Image of a world map showing fast fashion purchasing habits around the world. Source: Eerth.Org

A False Sense of Sustainability

Fast fashion brands have recently incorporated sustainability messaging to counteract the increasing public criticism. Sustainable manufacturing practices, recycled materials, and responsible sourcing are some of the claims that these brands are making. An example is H&M’s Conscious Choice products aim to ensure that each product under this line uses at least 50% more sustainable materials. This is one of the key alterations to the business model of the fashion industry that Niinimäki et al. (2020) detail in their article, but these changes are only superficial.

H&M is now being sued by Chelsea Commodore, a New York resident, for allegedly greenwashing their products. According to a lawsuit filed by the customer on July 22, the firm is capitalising on the rising number of consumers who are environmentally aware by developing a complete marketing campaign that greenwashes its products and claims that they are eco-friendly when they are not. According to the lawsuit, H&M’s advertisements also mislead customers into thinking that used clothing is merely recycled or that it will not end up in a landfill.

Well, What Are the Alternatives Then?

While individuals can’t fix systemic problems in the fast fashion industry on their own, change has to start somewhere. In this economy, the solution is not to purchase new overpriced clothing that markets itself as sustainable, but to repurpose and resell the clothes that we already have. Platforms such as Depop and Facebook Marketplace are ideal platforms to buy and sell second-hand clothing and shoes. But, of course, if you can afford sustainable and ethically made clothing, then go for it! As kia writes in her Hot Take “If you can’t buy ethically, then don’t buy at all”, affordability matters, but knowing that lower prices come at the cost of someone else’s safety and livelihood, should make us think twice before purchasing fast fashion.

“The Sustainable Revolution On Depop”. Source: Depop

Conclusion

Fast fashion is not a sustainable business model. Its dependence on cheap labour, overproduction and greenwashing mean that the way the industry operates is environmentally and socially untenable. The Rana Plaza collapse gave a human face to the cost of exploitation. A growing body of evidence has been illuminating its environmental impact. Greenwashing initiatives have given the impression of change, but these campaigns don’t tackle the problem at its root. It is by purchasing second-hand and only from sustainable and ethical businesses as alternatives are individuals able to combat fast fashion.

References

ABC News. (2014, January 3). At least three killed as Cambodian securityforces open fire on protesting garment workers. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-01-03/an-at-least-three-killed-as-cambodian-police-open-fire-on-prote/5184044

Ball, J. (2024, September 17). Leicester garment worker: “Working for £3 anhour made me feel dirty.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4ng1y78wppo

Bonanni, G., Nolan, J., & Pryde, S. (2024). Explainer: What is fast fashion and how can we combat its human rights and environmental impacts? Australian Human Rights Institute; UNSW Sydney. https://www.humanrights.unsw.edu.au/research/commentary/explainer-what-fast-fashion-human-rights-environmental-impacts

Clean Up Australia. (2025). Fast Fashion. Clean up Australia. https://www.cleanup.org.au/fastfashion

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2017). A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

Europa.eu. (2022, February 9). Microplastics from textiles: towards a circular economy for textiles in Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/microplastics-from-textiles-towards-a-circular-economy-for-textiles-in-europe

Gbor, N., & Chollet, O. (2024). Textiles waste in Australia Reducing consumption and investing in circularity. In The Australia Institute. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-Australia-Institute-Textiles-Waste-In-Australia-Web.pdf

GOV.UK. (2025). National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage Rates. https://www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage-rates

GreenAmerica. (2019). Toxic Textiles Report | Green America. https://greenamerica.org/green-americas-2019-toxic-textile-report

H&M. (2018). Conscious products explained. https://www2.hm.com/en_au/sustainability-at-hm/our-products/explained.html

H&M. (2025). Same Day Delivery. https://www2.hm.com/en_au/customer-service/same-day-delivery.html

Huynh, C. (2021). 10 Fast Fashion Brands We Avoid At All Costs. Good on You. https://goodonyou.eco/fast-fashion-brands-we-avoid/

Ignatescu, E. You’re better off throwing your clothes in the bin. – NETS2001 Writing on the Web. Netstudies.org. https://wotw.netstudies.org/2025/08/20/youre-better-off-throwing-your-clothes-in-the-bin/

Islam, Md. M., Aidid, A. R., Mohshin, J. N., Mondal, H., Ganguli, S., &

Chakraborty, A. K. (2025). A critical review on textile dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicity, health risks, and remediation strategies for environmental safety. Cleaner Chemical Engineering, 11, 100165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clce.2025.100165

Johnson, S. (2023). “It’s like a death pit”: how Ghana became fast fashion’s dumping ground. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jun/05/yvette-yaa-konadu-tetteh-how-ghana-became-fast-fashions-dumping-ground

Kia. (2025). If You Can’t Buy It Ethically, Don’t Buy It At All – NETS2001 Writing on the Web. Netstudies.org. https://wotw.netstudies.org/2025/08/21/if-you-cant-buy-it-ethically-dont-buy-it-at-all/

KnowESG. (2023, April 16). What Are The Main Greenwashing Tactics Companies Use? KnowESG. http://knowesg.com/featured-article/what-are-the-main-greenwashing-tactics-companies-use

Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. (2020). The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(4), 189–200. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9

Poerner, B. (2020, September 3). Where does clothing end up? Modern colonialism disguised as donation. Fashion Revolution. https://www.fashionrevolution.org/where-does-clothing-end-up modern-colonialism-disguised-as-donation/

Prentice, R. (2021). Labour Rights from Labour Wrongs? Transnational Compensation and the Spatial Politics of Labour Rights after Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza Garment Factory Collapse. Antipode, 53(6), 1767–1786. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12751

Pucker, K. P. (2022, January 13). The Myth of Sustainable Fashion. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/01/the-myth-of-sustainable-fashion

Sierra, B. (2024, August 17). H&M Is Being Sued for “Misleading” Sustainability Marketing. What Does This Mean for the Future of Greenwashing? The Sustainable Fashion Forum. https://www.thesustainablefashionforum.com/pages/hm-is-being-sued-for-misleading-sustainability-marketing-what-does-this-mean-for-the-future-of-greenwashing

SANVT. How Sustainable is Cotton? Organic Cotton vs Conventional Cotton. (2023, May 2). https://sanvt.com/blogs/journal/how-sustainable-is-cotton

WWF. (2014). Handle with Care. https://www.worldwildlife.org/magazine/issues/spring-2014/articles/handle-with-care