Imagine it is early morning, a student of the Gen Z sits up in bed, picks up the phone, and starts brushing their teeth. A quick brush, a few swipes on TikTok, a quick scroll on Discord, and brush their teeth for a couple of minutes. A quick breakdown of the day is all a Gen Z student needs before heading off for the day. For most of these youngsters and students their digital escapades is a mode for a quick social and interactive engagement. Apart from the boredom, social media channels these youngsters as a large integrated part of their day, social life, and digital self development.

Social media, in all forms, and flows to the younger generations is a given, and the real question is to what extent social media shapes how Gen Z gets to know and define themselves. Turkle, a social media and technology critique, states that social media interaction is purely superficial and real social connections are frayed and pretend. In contrast to these social media critics, there are social media positive social media scholars, that speak to organized social media movements, self-expression, and the sense of the community social media brings that one does not get in the real world.

The author of this article feels social media does not only destroy community or create community, but rather, it reconfigures it. Young people are able to transform their connections to one another on social media, and participate, perform their identity, and take part in activism in new ways. New social media patterns can, however, lead to challenges around authenticity, sustainability, and social pressure. Gen Z balances belonging and identity more seamlessly in the digital age than any previous generation.

Literary Context Outside of the Community: The Relationship Between Social Media and Community

Critics of social media focus on how it Facilitates superficial connections in place of meaningful relationships.

Sherry Turkle (2016) said that the “Illusion of Love and the Illusion of Intimacy” describes how constant digital communication provides a semblance of intimacy. True intimacy and connection are absent. People will lose dialogue and choose the solitude of a custom online space, Trust and empathy are absent in such shallow relationships. Turkle describes the “availability” of others and the constant “on” feeling of technology as a barrier to communication and reflection.

Other research noted constant connectivity culture not only tolerance but also the psychosocial burden. The American Psychology Association (APA, 2020) report states that “heavy social media use and social isolation” are “linked to anxiety, depression, and loneliness” in children and adolescents. Instagram and Tiktok are popular and highly visual platforms that promote unrealistic beauty and social standards. Perloff (2021) states negatively and with a high degree of “self-worth” in their “discourse” to “self-monitor” children and adolescents with a focus on digital validation.

From a critical viewpoint, “raging” social media is “community detrimental” on the basic underpinning of “disgenuine” social community. Companies and “raged” social media systems create addictive echo chambers which disconnect users negatively and are commercially motivated. Gen Z may think that online connections are quick and easy, but they may lack realness and emotional depth.

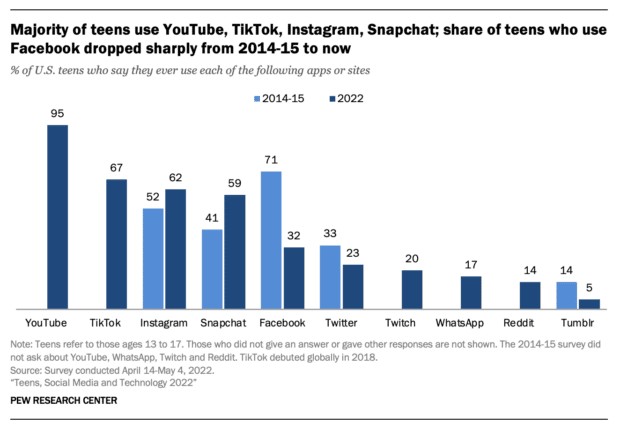

More recently published research, including that by Pew Research Center (2022), finds that nearly 70% of gen Z consider themselves part of online communities and networks, including social and political activism, fandoms, and gaming servers. These communities are special because they are not limited by community norms and culturally and geographically defined boundaries. Social media then stops being a mere communication tool and becomes a community around which ‘social’ and ‘active’ integration are possible.

Baym (2015) discusses that online interaction provides opportunities for people to explore and ‘play’ with different aspects of who they are. For many compared to real world social settings, digital spaces are especially safe and affirming, and supportive networks of people for LGBTQ+ youth and other marginalized populations. Similarly Watching Livingstone and Third (2017) For many young people social media provides a means to digital activism, and the exercise social and political rights of expression, association, and participation, in the world. This view doesn’t see online bonding as being lesser social and real community, but rather as a newly created form of social interaction.

In summary, social media itself is not the problem, and it is not the solution either.

Reality is complicated. There is the potential for empowerment, but there are also constraining conditions. There is inclusion and the possibility of self-expression, but there is also excessive self-surveillance, burnout, and self-comparison. Understanding the members of Generation Z in these conditions is no easy task. The challenges of belonging and identity are complex, and perhaps only the individuals concerned can answer them. Analysis and Argument: The Transformation of Community and Identity Focusing on the impact of social media on Generation Z and the formation of community simply in terms of “destruction” or “building” community overlooks the social, complex, and profound reorganization of community. The social coordination of community around interests, values, and aesthetics—often more important than geographical proximity—is readily observable on platforms like TikTok, Discord, and Instagram. There are subcultures on TikTok, for example, “BookTok” or “CleanTok,” and Discord communities for gaming or studying which demonstrate that digital communities can form structured hierarchies, and more traditional communities, in emotionally significant and meaningful ways, form bonds, inside jokes, and attachments. Moreover, these digital communities can also be fleeting. Social communities on the internet are especially prone to rapid change and evolution, and in some situations, complete dissolution.

Some connections are just temporary and this type of connection is called liquid belonging. It consists of some pods being chased while others are avoided.

Within online spaces, identity becomes a performance with a constant expectation of enactment. Ellison and Vitak allude to the fact that social media is a practice where users construct and manage a presentation. Social media for Gen Z is a constant feedback loop where they get responses to a performance and modify. People are expected to conform and create replicas of viral content and idealized versions of themselves which can limit confidence and creativity.

Having an “authentic self” is part of social media’s biggest debate. Critics argue that these performances ‘fake’ an identity, while Dissertation contends that identity is performative. The self presented on Instagram or TikTok is not untrue. It is a self presentation for a specific context, in this case, digital. For Gen Z, self identity performance is work that really straddles authenticity and strategy.

Having problems is inevitable. Certain social media “platforms” can create a sense of community and support, but those feelings have a tendency to fade, especially trend driven, and profit driven platforms. In the case of the Fridays for Future Activism, this is an example of real-world action coming out of online organizing. But not every online space is devoid of action in the real world. Some are completely empty. They seem to evaporate the moment a collective attention shifts.

Of the greatest stability are the communities that integrate online and offline participation. Sports teams, college clubs, and grassroots organizations set up Discord servers and an Instagram for coordination, and there is a reason for this. They see the value in the unity that is created in face-to-face meetings, workshops, and brainstorming sessions. These hybrid relational meetings, that also accommodate the digital-age youth for a need of flexibility, still make emotional and relational contact.

For younger people, there are digital “areas” in large supply. There are real areas that have communities and a sense of belonging, but that is also something to be considered about the many digital environments that have no set physical parameters. Creatively, a common idea and real online risk, for community joined together. There are, after all, ways social media can improve, not destroy, community.

Generation Z is shaped by social media in community and identity.

People worry that new digital media won’t engage or be meaningful. They forget about new digital media’s potential for innovation, participation, and a sense of belonging. It’s true that new media tools can provide contradictory experiences. They can enable collective participation, but that participation will still have tensions of authenticity, performativity, and participation.

Instead of asking whether social media is ‘good’ or ‘bad’, it’s more useful to think about how Gen Z and the world can create a responsible, sustainable sense of belonging that’s digitized. With a more transformational focus that is mindful and critical, the combination of hybrid-connection and digital literacy will shift the quality of more ephemeral, digital relations toward lasting, meaningful relationships. Social media should not be viewed as a utopia or dystopia; it is a reflection of social reality. To have true community and authenticity work in harmony, digital spaces for Gen Z should be transformed, not discarded.